Executive Summary

America encompasses a rich diversity of faith traditions, and “religious churning” is very common. In 2023, PRRI surveyed more than 5,600 adults across the United States about their experiences with religion. This report examines how well major faith traditions retain their members, the reasons people disaffiliate, and the reasons people attend religious services. Additionally, this report considers how atheists and agnostics differ from those who say they are “nothing in particular.” Finally, it analyzes the prevalence of charismatic elements as well as prophecy and prosperity theology in American churches and the role of charismatic Christianity in today’s Republican Party.

“Unaffiliated” is the only major religious category experiencing growth.

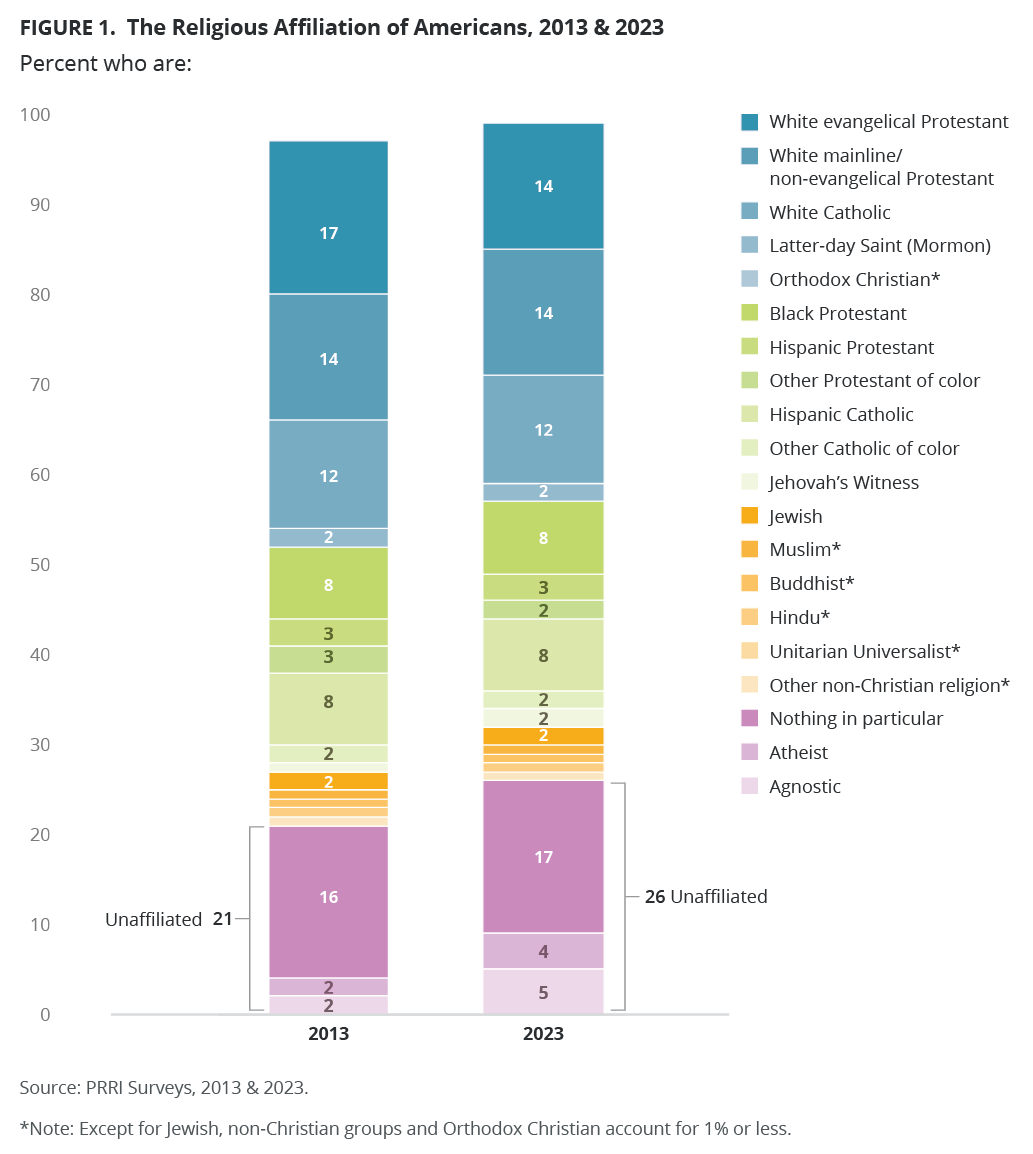

- Around one-quarter of Americans (26%) identify as religiously unaffiliated in 2023, a 5 percentage point increase from 21% in 2013. Nearly one in five Americans (18%) left a religious tradition to become religiously unaffiliated, over one-third of whom were previously Catholic (35%) and mainline/non-evangelical Protestant (35%).

- While the percentage of Americans who describe themselves as “nothing in particular” is similar to a decade ago (16% in 2013 to 17% in 2023), the numbers of both atheists and agnostics have doubled since 2013 (from 2% to 4% and from 2% to 5%, respectively).

Catholic loss continues to be highest among major religious groups; white Evangelical retention rate has improved since 2016.

- Catholics continue to lose more members than they gain, though the retention rate for Hispanic Catholics (68%) is somewhat higher than for white Catholics (62%).

- White mainline/non-evangelical Protestants also continue losing more members than they replace and at higher rates than other Protestants.

- The net loss of members among white evangelical Protestants has declined since 2016. In 2023, white evangelical Protestants have one of the highest retention rates of all religious groups (76%), an improvement since 2016, when white evangelicals retained just two in three members (66%).

- Black Protestants (82%) and Jewish Americans (77%) enjoy the highest retention rates of all religious groups.

- The rates of religious churning for Hispanic Protestants, Latter-day Saints, and Jewish Americans result in zero net gains or losses.

While most disaffiliate because they stop believing, religious teachings on the LGBTQ community and clergy sexual abuse now play a more prominent role.

- The reason given by the highest percentage of religiously unaffiliated Americans for leaving their faith tradition is that they simply stopped believing in their religion’s teachings (67%).

- In 2016, approximately three in ten people who left their religion cited negative teaching about or treatment of gay and lesbian people as an important factor in their choice to disaffiliate (29%); in 2023, that number rose to 47%.

- The percentage of religiously unaffiliated Americans who say they no longer identify with their childhood religion due to clergy sexual abuse scandals rose by more than 10 percentage points, from 19% in 2016 to 31% in 2023. Former Catholics are more likely than former non-Catholics to say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because of sexual abuse scandals (45% vs. 24%).

The religiously unaffiliated are not a monolith.

- Similar to the racial and ethnic breakdown of all Americans, the majority of religiously unaffiliated Americans are white (65%), 16% are Hispanic, 8% are Asian American or Pacific Islander, 7% are Black, and 3% identify with another race. However, atheists and agnostics are more likely than those who identify as nothing in particular to be white (75% and 72% vs. 61%)

- Compared with all Americans, the unaffiliated are notably more likely to identify as Democrats (35% vs. 29%) and independents (38% vs. 30%), and substantially less likely to identify as Republican (12% vs. 29%)

- Unaffiliated Americans are twice as likely as all Americans to identify as LGBTQ (19% vs. 9%), including 23% of atheists, 19% of those who are nothing in particular, and 16% of agnostics.

Most unaffiliated Americans are not looking for a religious or spiritual home.

- Between 2016 and 2023, retention rates among the religiously unaffiliated increased 10 points from 66% in 2016 to 76% in 2023; very few Americans grow up without a religious identity and then join a religion later in life (3%).

- Just four in ten unaffiliated Americans describe themselves as spiritual. Across party lines, similar percentages of religiously unaffiliated Democrats (39%), independents (38%), and Republicans (35%) consider themselves to be spiritual.

- The vast majority of the religiously unaffiliated appear content to stay that way — only 9% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say the statement “I am looking for a religion that would be right for me” currently describes them very or somewhat well.

Church attendance among Americans is down and fewer Americans say religion is important; most Americans who attend religious services do so to feel closer to God.

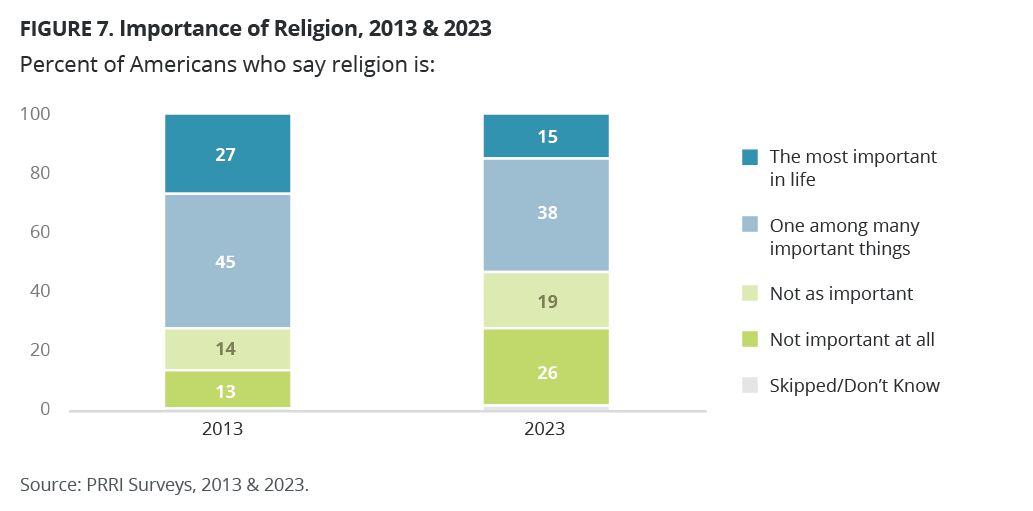

- A slim majority of Americans (53%) say that religion is the most important (15%) or one among many important things in their lives (38%) in 2023, notably lower than it was in 2013 when 72% of Americans reported that religion was the most important thing in their lives (27%) or one among many (45%).

- Republicans (22%) are twice as likely as independents (12%) and Democrats (11%) to report religion as the most important thing in their lives in 2023.

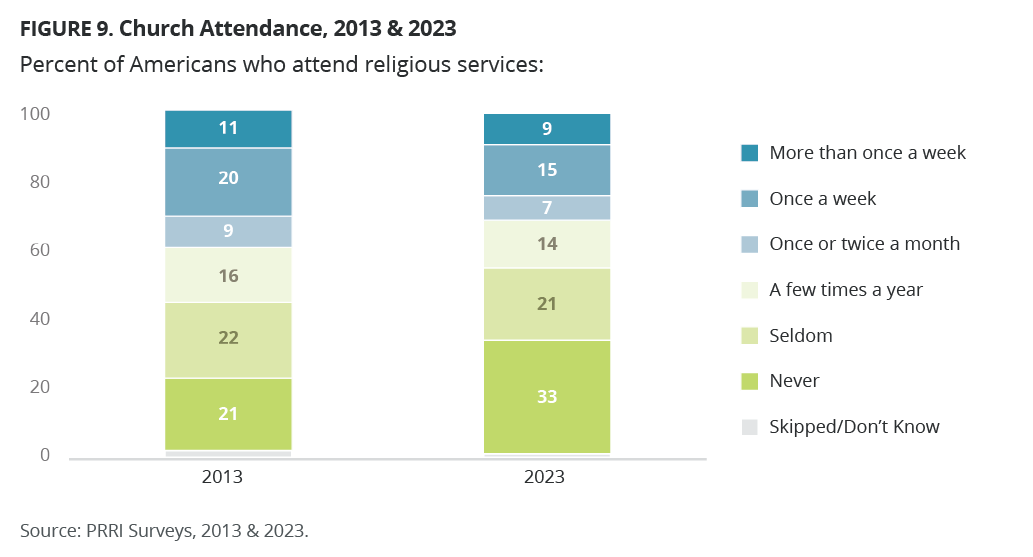

- In 2023, nearly one-quarter of Americans (24%) attend religious services, either virtually or in person, at least once a week, a 7 percentage point decline from 31% in 2013. Similarly, around two in ten Americans (21%) say they attend church services once or twice a month or a few times a year in 2023, a decline of 4 percentage points from 25% in 2013.

- Among religious service attendees, solid majorities across party, religion, age, and education levels report feeling closer to God, experiencing religion as a community, and instilling religious values in children as very or somewhat important reasons why they attend. Even among attenders under 30, a majority name those three as reasons why they attend religious services.

Exploring the prevalence of charismatic elements in American churches.

- Half of American churchgoers say they have received a definitive answer to a specific prayer (50%), nearly four in ten say the “Spirit” has empowered them or someone else to do a specific task (39%), three in ten say they have received a direct revelation from God (29%) or witnessed divine healing of an injury or illness (27%), and roughly two in ten have seen people speaking in tongues (21%) in the past year.

- Among church attenders, Republicans are more likely than independents and Democrats to say they have received a definitive answer to a specific prayer (57% vs. 46% and 44%, respectively) and that the “Spirit” empowered them or someone else to do a specific task (44% vs. 37% both). By contrast, Democrats (26%) are more likely than Republicans (19%) to have witnessed people speaking in tongues. Both Republicans (30%) and Democrats (28%) are more likely than independents (22%) to say they witnessed divine healing of an injury or illness.

- Church attenders report experiencing or witnessing 1.7 charismatic elements while attending a religious service in the past year, with 3 in 10 Americans experiencing three or more events. Republican and Democratic churchgoers are equally likely to have experienced or witnessed at least three charismatic elements while attending religious services.

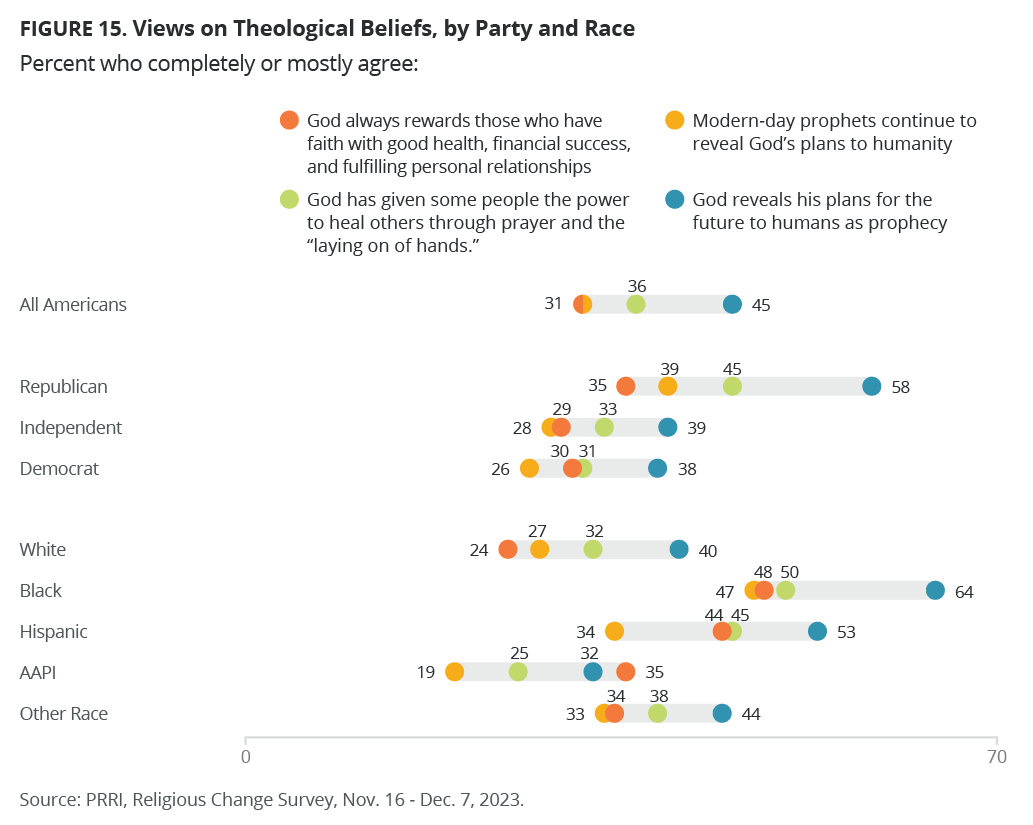

Prophetic and Prosperity theological beliefs are more common among Republicans and African Americans.

- Over four in ten Americans agree that “God reveals his plans for the future to humans as a prophecy” (45%). Roughly one-third of Americans agree with the statements that “God has given some people the power to heal others through prayer and the ‘laying on of hand’” (36%), “modern-day prophets continue to reveal God’s plan to humanity” (31%), and “God always rewards those who have good faith with good health, financial success, and fulfilling personal relationships” (31%).

- Black Americans tend to agree more with all these theological beliefs than white, Hispanic, AAPI, and other race Americans.

- Republicans are more likely than independents and Democrats to hold such beliefs.

Religion and the MAGA Movement: The Role of Charismatic Christianity and Prophecy/Prophetic Beliefs in the Republican Party

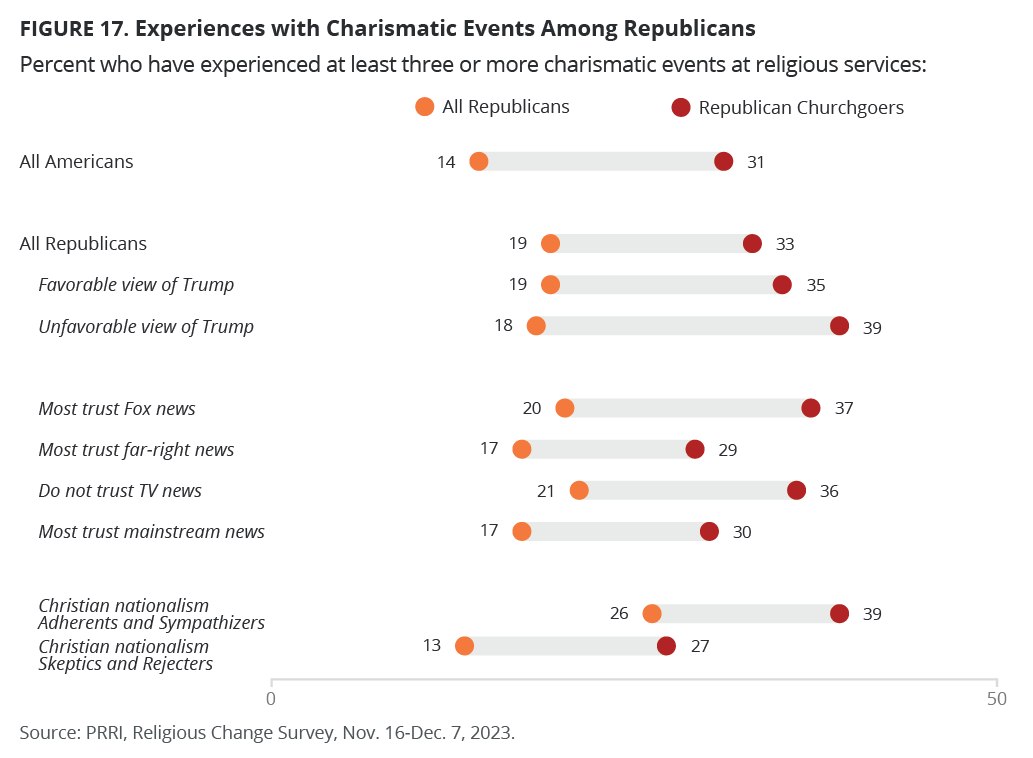

- Approximately one-third of Republicans who attend church at least a few times a year indicated that they attended a religious service where they had experienced themselves, or witnessed, at least three charismatic elements. However, just 19% of Republicans overall, which includes Republicans who rarely, if ever attend church, have experienced such charismatic elements in the past year.

- Republican Christian nationalists are significantly more likely than non-Christian nationalist Republicans to have witnessed or experienced at least three charismatic events in the past year.

- There is little support for the idea that churchgoing Trump supporters within the GOP are disproportionately likely to experience charismatic religious practices than Republican churchgoers who hold unfavorable views of Trump.

- Republican churchgoers who qualify as Christian nationalism adherents and sympathizers are more likely than those who qualify as skeptics and rejecters to have witnessed or experienced charismatic events.

- Republicans who hold a favorable view of Trump score higher on our scale that measures prophetic and prophecy beliefs than Republicans who hold unfavorable views of Trump.

Introduction

America encompasses a rich diversity of faith traditions. While many Americans identify with the religion in which they were raised, others choose different religious paths as adults for a variety of reasons, including marriage into a new faith tradition, relocation to a new area, or a change in theological views. This “religious churning” is very common in the United States. In 2022, PRRI found that about one in four Americans say they were previously a follower or practitioner of a different religious tradition or denomination than the one they belong to now. Other American religious demography studies estimate the number of religious switchers at higher rates.[1]

This report takes a closer look at religious change in America, examining which major faith traditions have done better at retaining members and which have fared worse. In the United States today, the only major religious category experiencing widespread growth is the religiously unaffiliated. This report delves deeper into why people continue to disaffiliate with religion, including new analysis that considers how self-professed atheists and agnostics differ from Americans who say they are “nothing in particular.”

While the percentage of religious “nones” is growing, roughly three in four Americans continue to identify with a specific faith tradition, and many Americans engage in religious practices routinely, including regular church attendance. Our report considers the reasons that many Americans continue to attend religious services.

Finally, we consider the extent to which Americans who attend church regularly have experienced or witnessed charismatic elements while attending those religious services. We also study the extent to which Americans hold prophetic theological views and beliefs associated with the prosperity gospel.

Religious Affiliation in America

The majority of Americans continue to identify as Christian (67%). However, the proportion of the U.S. population who identifies as white Christians has declined from 46% in 2013 to 42% in 2023, while the proportion of Christians of color has remained steady (from 24% to 25%). This partly reflects demographic shifts in the U.S. population as the nation becomes less white.

Among white Christian groups, the largest decline in the past decade took place among white evangelical Protestants, whose numbers saw a 3 percentage point decrease, from 17% in 2013 to 14% in 2023. In 2023, the percentages of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (14%) and white Catholics (12%) remain largely similar to those of 2013. Regarding Christians of color, the share of Hispanic Catholics (8%) and Hispanic Protestants (3%) also remain largely the same since 2013.

Black Protestants continue to make up 8% of the American population, a proportion that has not changed since 2013. Similarly, fewer than one in ten Americans identify as Protestants of color (2%), non-Hispanic Catholics of color (2%), Latter-day Saints (2%), Jehovah’s Witnesses (2%), or Orthodox Christians (<1%) — percentages that have remained steady since 2013.

Less than 5% of Americans identify as members of non-Christian religions, which is unchanged since 2013, including Jewish Americans (2%), Muslims (1%), Buddhists (1%), Hindus (<1%), and Unitarian Universalists (<1%).

Americans have also become less religious over the course of a decade. Around one-quarter of Americans (26%) identify as religiously unaffiliated in 2023, a 5 percentage point increase from 21% in 2013. Roughly two in ten Americans (17%) describe themselves as “nothing in particular,” similar to 2013 when 16% of Americans identified as such. By contrast, the number of atheists (from 2% to 4%) and agnostics (from 2% to 5%) has doubled since 2013.

Religious Switching in America: Winners and Losers in the American Religious Marketplace

Overview of Religious Switchers

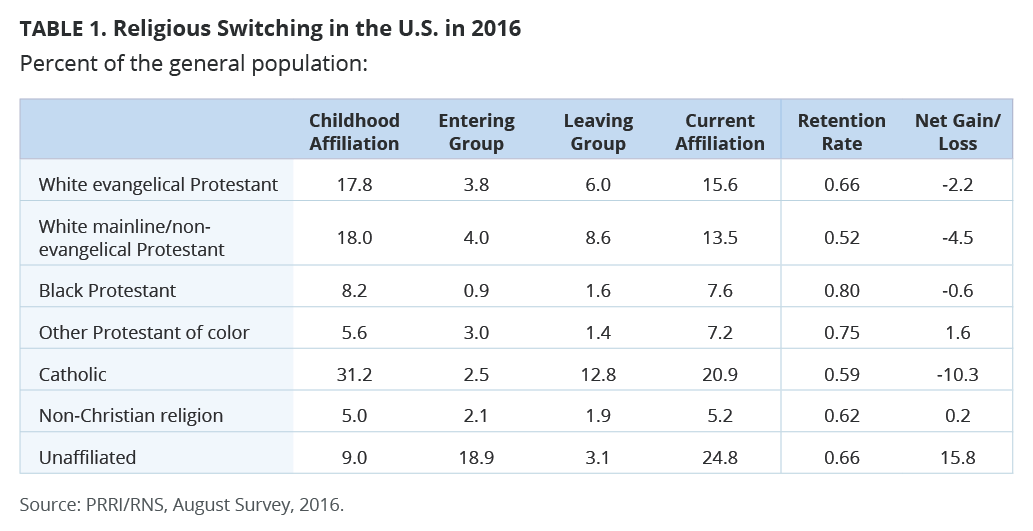

In 2016, PRRI published data that examined the rate of religious switching in America, referring to individuals who left their childhood faith tradition as adults. We found that the religiously unaffiliated benefited most directly from this religious switching. Nearly one in five Americans (19%) switched from their childhood religious identity to become unaffiliated as adults; relatively few Americans (3%) who were raised unaffiliated joined a religious tradition. In 2016, two-thirds of Americans raised without a religious tradition stayed religiously unaffiliated as adults.

In 2016, Protestants of color and non-Christian religious groups remained fairly stable in terms of those who entered or left. However, white Protestants and Catholics experienced declines, with Catholics suffering the largest decline among major religious groups — a 10 percentage point loss overall. In 2016, nearly one-third of Americans (31%) reported being raised in a Catholic household, but only about one in five Americans (21%) identified as Catholics that year. Thirteen percent of Americans reported being former Catholics, and roughly 3% of Americans had left their religious tradition to join the Catholic Church. White evangelical Protestants and white mainline Protestants also witnessed negative growth, but to a much more modest degree (-2 percentage points and -5 percentage points, respectively).

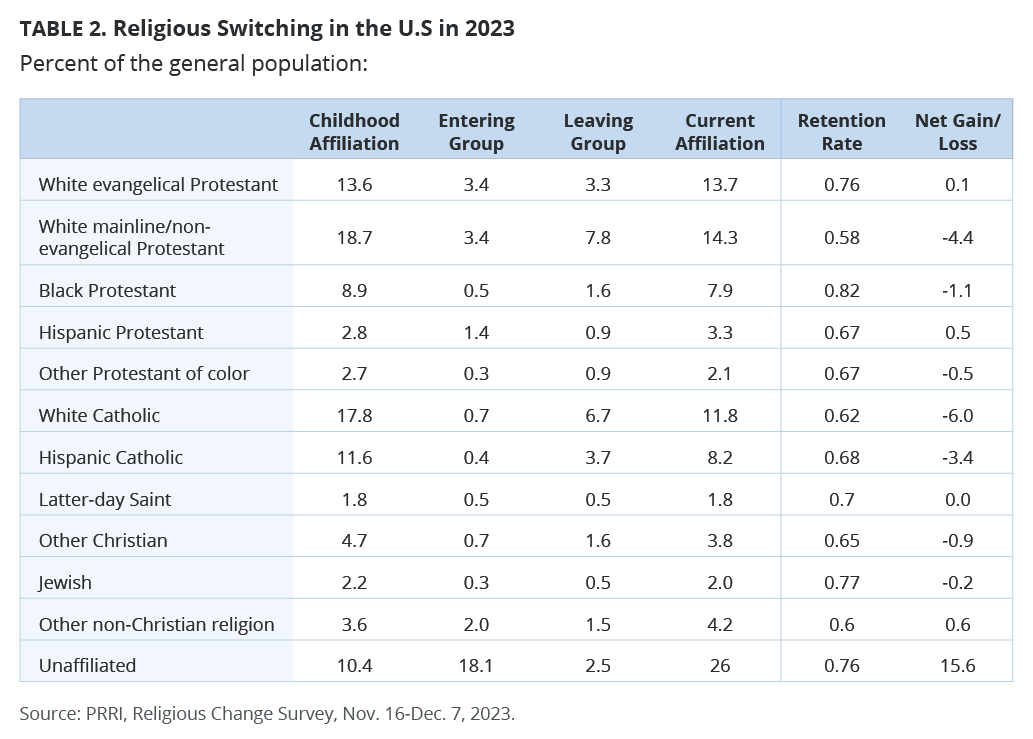

In 2023, one in ten Americans (10%) report growing up without a religious identity, while 18% of Americans say they became unaffiliated after growing up in another religious tradition. In comparison, very few Americans who grew up without a religious identity joined another religion later in life (3%). Retention rates among the religiously unaffiliated also increased from 66% in 2016 to 76% in 2023. In total, 26% of Americans identify as religiously unaffiliated in 2023 — the only religious category that has gained large numbers of members in the religious marketplace in the past decade.

Among Christian groups, Catholics as a whole continue to lose more members than they gain, though the retention rate for Hispanic Catholics (68%) is somewhat higher than for white Catholics (62%). Consistent with 2016, Catholics have experienced the largest decline in affiliation of any religious group. In 2023, 18% of Americans grew up as white Catholics, but just 12% of white Catholics continue to identify as members of their childhood faith. In 2023, 12% of Americans grew up as Hispanic Catholic; now just 8% of Americans identify as such.

Among the 11% of Americans who are former Catholics, the majority now identify as unaffiliated (55%), and one in ten identify as white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (11%), white evangelical Protestants (10%), or Hispanic Protestants (10%). Seven percent of former Catholics identify as members of other Christian traditions and 5% identify as members of non-Christian religions.[2]

Similar to our 2016 analysis, white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants continue losing more members than they replace and at higher rates than other Protestants. The retention rate for Black Protestants has also stayed largely the same since 2016 (82%) and is among the highest of all religious groups.

The net loss of members among white evangelical Protestants has declined since 2016. In 2023, white evangelical Protestants enjoy one of the highest retention rates of all religious groups (76%). This rate has improved since 2016, when white evangelicals retained just two in three members (66%).

In 2023, the rates of religious churning for Hispanic Protestants, Latter-day Saints, and Jewish Americans result in zero net gains or losses in terms of their representation in the overall U.S. religious landscape. Jewish Americans in particular have a relatively strong retention rate compared with other faith traditions, retaining more than three in four members into adulthood (77%).

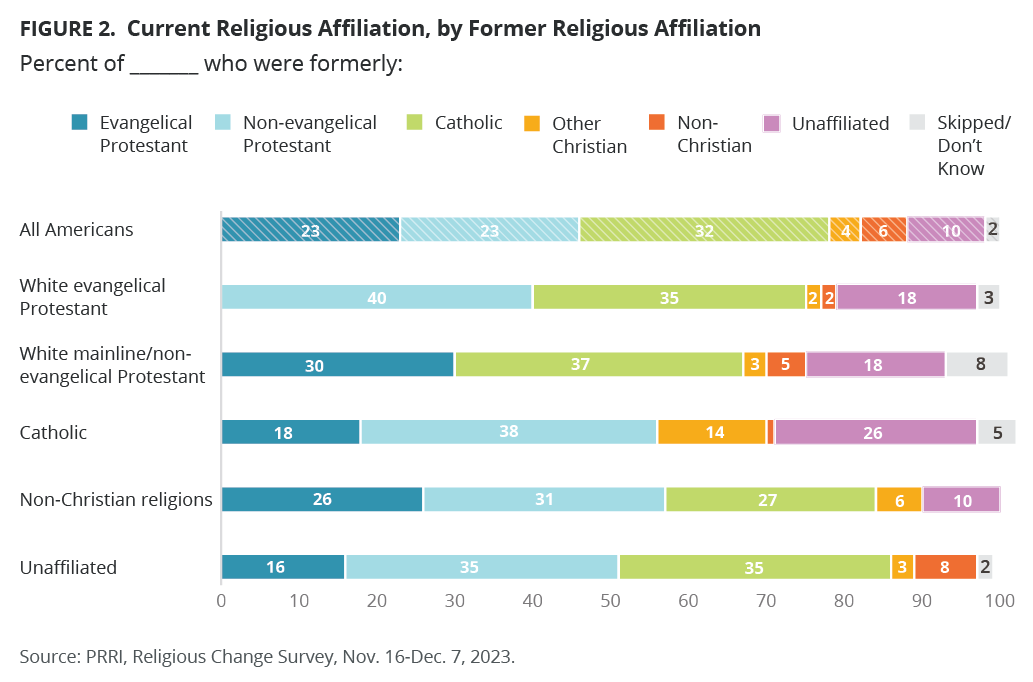

An In-Depth Look at Religious Switchers

Approximately 3% of Americans now identify as white evangelical Protestants though they were brought up in a different or no faith tradition, drawing mainly from former mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (40%) and Catholics (35%). Roughly one in five of today’s white evangelical Protestants (18%) were previously unaffiliated. Around 4% were previously other Christians or belonged to other non-Christian traditions.

About 3% of Americans who were raised in a different tradition now identify as mainline/non-evangelical Protestants. Among this group, 37% were previously Catholic, 30% were evangelical Protestants, 3% belonged to other Christian religions, and 5% belonged to other non-Christian traditions. Nearly two in ten of those who switched to identify as white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants were previously unaffiliated (18%).

Only 1% of Americans converted to Catholicism as adults, including 38% who were raised as non-evangelical Protestants. Eighteen percent were previously evangelical Protestants, 14% belonged to other Christian traditions, and just 1% were non-Christians. One in four Catholic converts were previously unaffiliated (26%).[3]

Nearly one in five Americans (18%) left a religious tradition to enter the ranks of the religiously unaffiliated, over one-third of whom were Catholics (35%) and mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (35%). The ranks of unaffiliated switchers are less likely to be drawn from former evangelical Protestants (16%), other non-Christian traditions (8%), or other Christian traditions.

Reasons Those Who Left Their Childhood Faith Became Religiously Unaffiliated

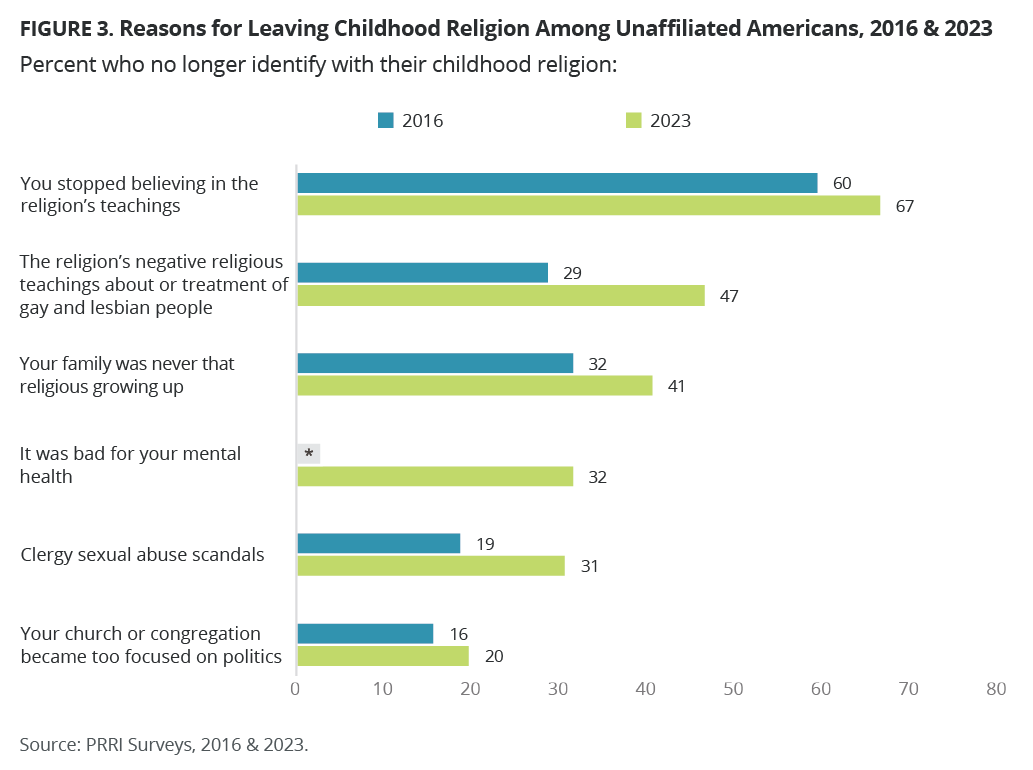

In 2016, we asked Americans why they left their childhood faith to become religiously unaffiliated. The most popular reason cited was that they simply stopped believing in their religion’s teachings (60%). Today, this reason remains the predominant factor in explaining why religiously unaffiliated Americans no longer identify with their childhood faith: More than two in three such religiously unaffiliated Americans indicate it is an important reason they have disaffiliated (67%).

The role of LGBTQ issues, however, has taken a much more prominent role among Americans who were raised within faith traditions but disaffiliated. In 2016, approximately three in ten cited negative teaching about or treatment of gay and lesbian people as an important factor in their choice to disaffiliate with their childhood religion (29%). In 2023, that percentage rose to 47%.

Similarly, the number of unaffiliated Americans who say their family was “never that religious growing up” or mention clergy sexual abuse scandals as another reason for disaffiliation increased by roughly 10 percentage points, from 32% to 41% and 19% to 31%, respectively, from 2016 to 2023. Fewer religiously unaffiliated Americans mention their church or congregations becoming too focused on politics (20%), though this reason elicits more support than in 2016 (16%). Instead, unaffiliated Americans are more likely to mention their mental health as a reason why they left (32%).[4]

Reasons for No Longer Identifying with Childhood Religion Among Subgroups

In some cases, the reasons that Americans have become disaffiliated from their childhood religion differ by partisanship, age, LGBTQ status, and race/ethnicity. The saliency of these reasons also differs among atheists, agnostics, and those religiously unaffiliated who simply describe themselves as “nothing in particular.”

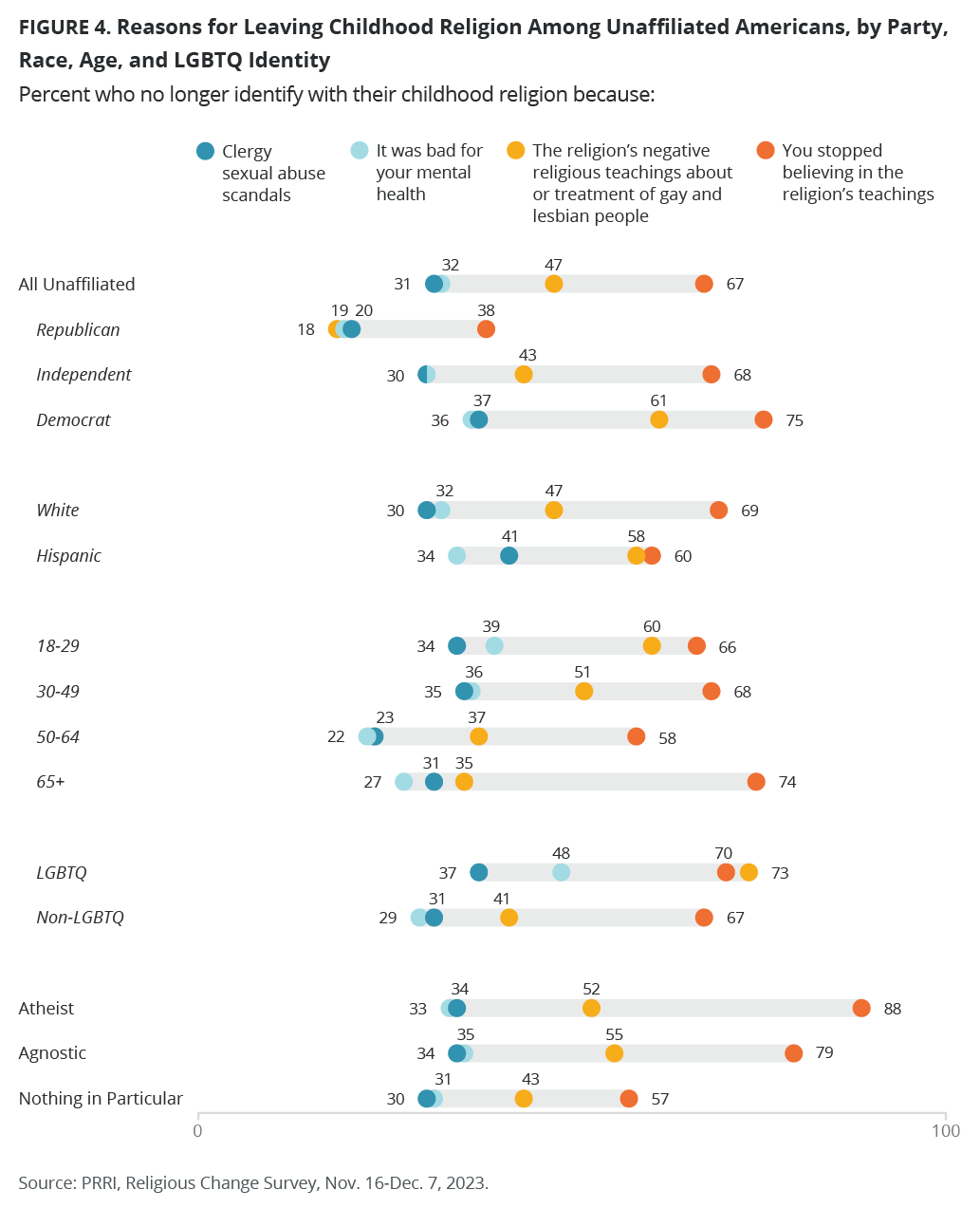

Stopped Believing in the Religion’s Teachings

Nearly two-thirds of unaffiliated Americans (67%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because they stopped believing its teachings. Religiously unaffiliated Democrats (75%) and independents (68%) are about twice as likely as Republicans (38%) to report this as a reason for leaving their religion.

White unaffiliated Americans (69%) are slightly more likely than Hispanic unaffiliated Americans (60%) to name this as a reason.[5] Unaffiliated Americans age 65 or over (74%) are the most likely to say they stopped believing, compared with younger groups, including 58% of unaffiliated ages 50-64, 68% unaffiliated ages 30-49, and 66% of young unaffiliated under the age of 30.

Most atheists (88%) and agnostics (79%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because they stopped believing and at significantly higher rates compared with 57% of Americans who identify as nothing in particular.

Religion’s Negative Teachings About LGBTQ People

Another important reason why religiously unaffiliated Americans report that they no longer identify with their childhood religion is due to that religion’s teachings about LGBTQ people (47%). There are strong party distinctions on this front. The majority of religiously unaffiliated Democrats (61%) and 43% of independents report this as a reason for leaving the church, compared with only 18% of unaffiliated Republicans.

Along racial lines, unaffiliated Hispanic Americans (58%) are more likely than unaffiliated white Americans (47%) to name this reason. Disaffiliation for this reason is also strongly linked to age. Six in ten young unaffiliated under 30 (60%) say they left their religious tradition over its teachings and treatment of LGBTQ Americans, compared with 51% of unaffiliated ages 30-49, 37% of unaffiliated ages 50-64, and 35% of unaffiliated age 65 or over.

The vast majority of LGBTQ unaffiliated Americans (73%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because of that religion’s negative teachings about LGBTQ people, compared with 41% of unaffiliated Americans who don’t identify as LGBTQ.

Slim majorities of Americans who identify as agnostic (55%) or atheist (52%) say they disaffiliated from their childhood religion due to that religion’s negative teachings about LGBTQ people, compared with 43% of those who identify as nothing in particular.

Family Was Never That Religious Growing Up

Four in ten unaffiliated Americans say that a reason why they no longer identify with a particular religion is because their family was never that religious growing up (41%). More religiously unaffiliated Republicans (49%) name this reason, compared with four in ten unaffiliated Democrats (39%) and independents (40%).

Over four in ten white unaffiliated Americans (41%) name this as a reason they left their faith traditions, compared with one-third of Hispanic unaffiliated Americans (35%). LGBTQ unaffiliated Americans are less likely than those who don’t identify as LGBTQ to say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because their family was never that religious growing up (33% vs. 43%).

Among both agnostic Americans and Americans who identify as nothing in particular, 41% say they no longer affiliate with their childhood religion because their families were never that religious growing up, compared with over one-third of atheists (36%).

Clergy Sexual Abuse Scandals

Slightly more than three in ten religiously unaffiliated Americans say they no longer identify with their childhood religion due to clergy sexual abuse scandals (31%). Former Catholics are more likely than former non-Catholics to say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because of church sex scandals (45% vs. 24%).

Unaffiliated Democrats (37%) are more likely than unaffiliated independents (30%) and unaffiliated Republicans (20%) to say they disaffiliated due to these scandals.

Four in ten unaffiliated Hispanic Americans (41%) and 30% of all unaffiliated white Americans report these scandals as a reason for disaffiliating. Except for unaffiliateds ages 50-64 (23%), roughly three in ten unaffiliateds under 30 (34%), unaffiliateds ages 30-49 (35%), and those 65 or older (31%) also mention these scandals as a reason for disaffiliating.

LGBTQ unaffiliated Americans are slightly more likely than those who don’t identify as LGBTQ to say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because of church sex scandals (37% vs. 31%).

Thirty-four percent of agnostics and atheists, as well as 30% of Americans who identify as nothing in particular, report clergy sexual abuse scandals as one of the reasons why they disaffiliated from their childhood religion.

Church or Congregation Became Too Focused on Politics

Two in ten unaffiliated Americans (20%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because their church or congregation became too focused on politics. The same is true across unaffiliated partisans, by race, age, and LGBTQ identity, as well as among agnostics, atheists, and those who identify with nothing in particular.

Religion was Bad for Mental Health

One-third of religiously unaffiliated Americans (32%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because the religion was bad for their mental health. Nearly half of LGBTQ unaffiliated Americans (48%) say they no longer identify with their childhood religion because it was bad for their mental health, compared with 29% of the unaffiliated who don’t identify as LGBTQ.

Unaffiliated Democrats (36%) are more likely than unaffiliated independents (30%) and unaffiliated Republicans (19%) to say their childhood religion was bad for their mental health.

Unaffiliated Americans under 50 are more likely than the unaffiliated over 50 to say that religion was bad for their mental health; this includes 39% of unaffiliateds ages 18-29, 36% of unaffiliateds ages 30-49, 22% of unaffiliateds ages 50-64, and 27% of unaffiliateds 65 or older.

Profile of All Unaffiliated Americans and Their Relationship to Religion

Who Are the Religiously Unaffiliated Today?

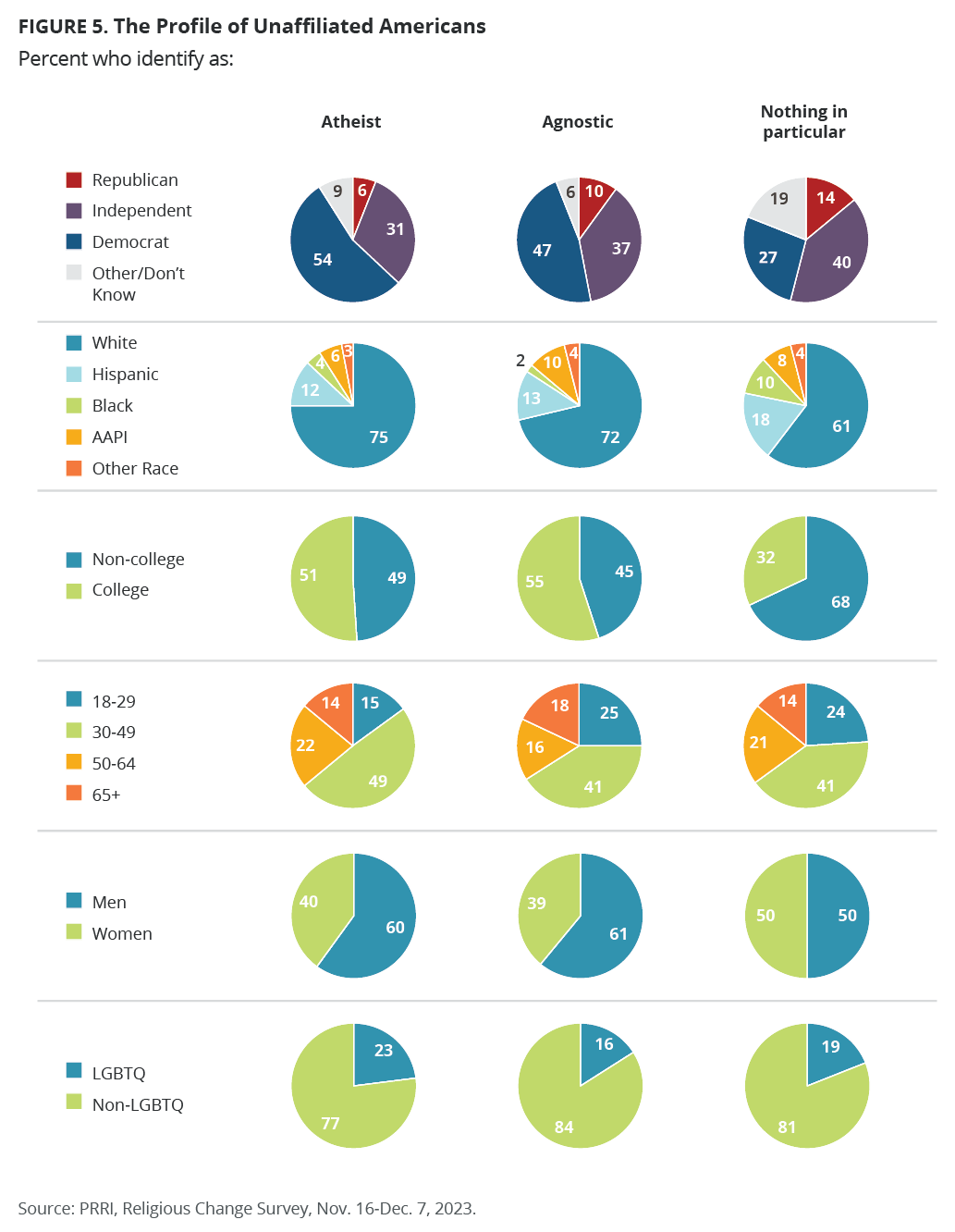

The religiously unaffiliated are not a monolithic group, as atheists and agnostics are often distinctive with respect to partisanship, race, education, and gender, compared with those unaffiliated Americans who claim they are “nothing in particular.”

Compared with all Americans, the unaffiliated are notably more likely to identify as Democrats (35% vs. 29%) and independents (38% vs. 30%), and substantially less likely to identify as Republicans (12% vs. 29%). Yet atheists (54%) and agnostics (47%) are about twice as likely as those who identify as those who are nothing in particular to identify (27%) as Democrats. By contrast, atheists (31% and 6%, respectively) are less likely than agnostics (37% and 10%, respectively) and those who identify as nothing in particular (40% and 14%, respectively) to identify as independents and Republicans.

The majority of religiously unaffiliated Americans are white (65%), 16% are Hispanics, about one in ten identify as Black (7%) or Asian American Pacific Islander (8%), and 3% identify with another race, which is similar to the racial and ethnic breakdown of all Americans. However, atheists and agnostics are more likely than those who identify as nothing in particular to be white (75% and 72% vs. 61%) and less likely to identify as Americans of color (25% and 29% vs. 40%).

While there are no meaningful educational differences between unaffiliated Americans and all Americans, the majority of atheists (51%) and agnostics (55%) have a college degree, compared with one-third of those who identify as nothing in particular (32%). Unaffiliated Americans tend to be younger than all Americans: ages 18-29 (23% vs. 19%), ages 30-49 (42% vs. 33%), ages 50-64 (20% vs. 26%), and seniors 65 and over (15% vs. 22%). There are no significant differences in age among atheists and agnostics.

Men are far more likely to identify as atheists (60%) and agnostics (61%) than women (40% and 39%, respectively), while those who identify as nothing in particular are equally likely to be men (50%) or women (50%). In addition, unaffiliated Americans are twice as likely as all Americans to identify as LGBTQ (19% vs. 9%), including 23% of atheists, 19% of those who identify as nothing in particular, and 16% who identify as agnostics.

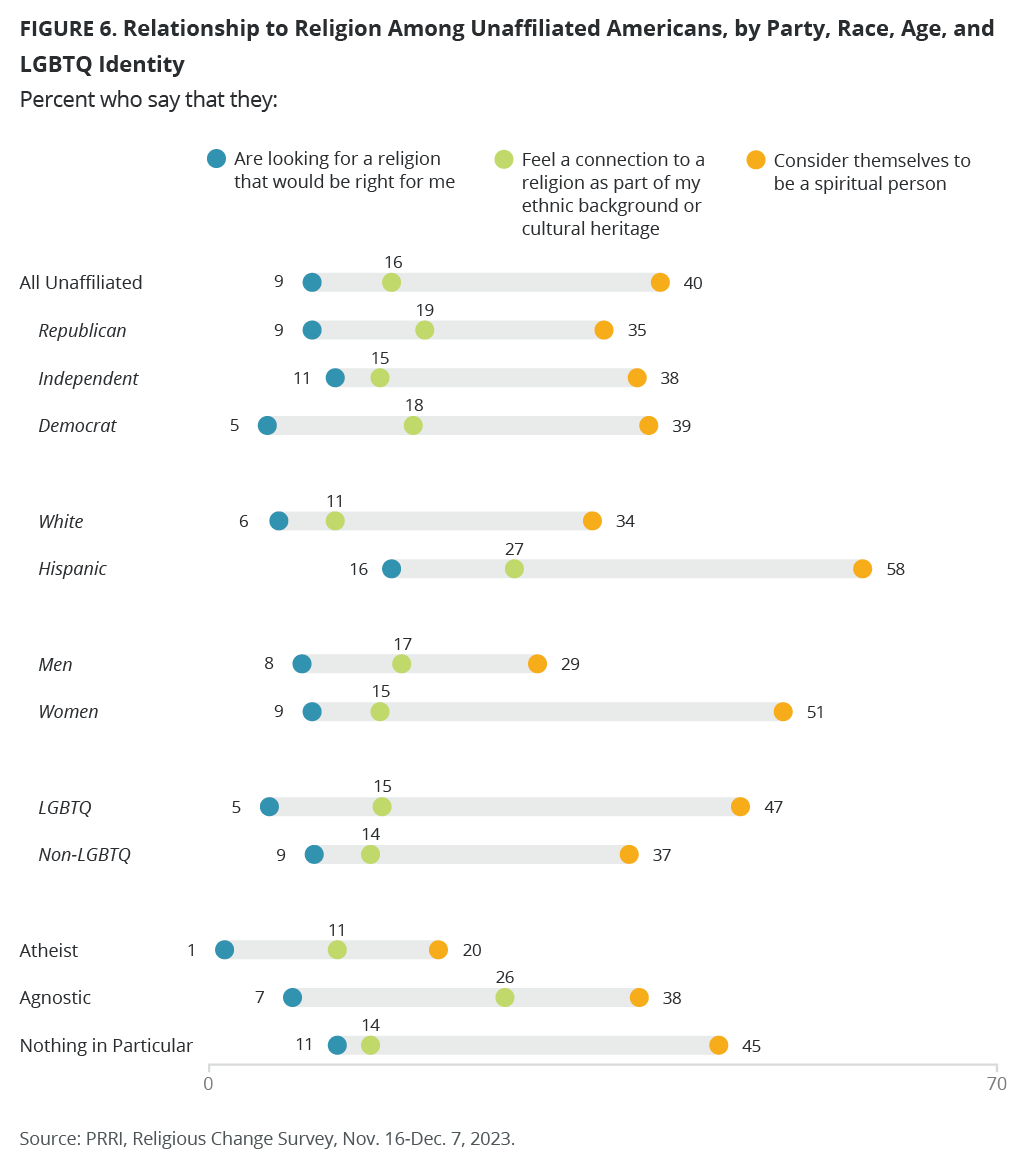

Identifying as Spiritual

Just four in ten unaffiliated Americans describe themselves as spiritual. Across party lines, four in ten or fewer religiously unaffiliated Democrats (39%), independents (38%), and Republicans (35%) consider themselves to be spiritual. Religiously unaffiliated Americans who identify as nothing in particular (45%) are the most likely to consider themselves spiritual, followed by 38% of agnostics and 20% of atheists.

However, the majority of Hispanic religiously unaffiliated Americans (58%) consider themselves to be spiritual, compared with one-third of white religiously unaffiliated Americans (34%).

Unaffiliated women (51%) are notably more likely than unaffiliated men (29%) to describe themselves as spiritual. LGBTQ unaffiliated Americans (47%) are also more likely than non-LGBTQ unaffiliateds (37%) to describe themselves as spiritual.

Looking for a Religion That Would Be a Right Fit

The vast majority of the religiously unaffiliated appear content to stay that way — only 9% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say the statement “I am looking for a religion that would be right for me” currently describes them very or somewhat well. Both religiously unaffiliated independents (11%) and Republicans (9%) are about twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated Democrats (5%) to say they are currently looking for a new religion.

Religiously unaffiliated Hispanic Americans (16%) are more than twice as likely as religiously unaffiliated white Americans (6%) to be currently looking for a religion that is right for them.

One in ten unaffiliated Americans who identify as nothing in particular (11%), 7% of agnostics, and just 1% of atheists say they are currently looking for a religion.

Connection to Religion as Part of Childhood Background or Cultural Heritage

Under two in ten religiously unaffiliated Americans (16%) say the statement “I feel a connection to a religion as part of my ethnic background or cultural heritage” describes them very or somewhat well. Around two in ten unaffiliated Republicans (19%), independents (15%), and Democrats (18%) say the same.

There are large differences across racial lines. Unaffiliated Hispanic Americans (27%) are more than twice as likely as unaffiliated white Americans (11%) to feel a connection to a religion as part of their childhood or cultural backgrounds.

In addition, agnostics (26%) are more than twice as likely as atheists (11%) and 12 percentage points more likely than unaffiliated who identify as nothing in particular (14%) to feel connected to a religion as part of their childhood background or cultural heritage.

Among unaffiliated Americans (25%), one in four report that their parents/guardians were from different religious backgrounds.

Not surprisingly, just one in ten religiously unaffiliated Americans (9%) report religious practices as an important part of their family’s home life each week.

Religiosity Among All Americans

Decline in the Importance of Religion Over the Past Decade

A slim majority of Americans (53%) say that religion is the most important (15%) or one among many important things in their lives (38%) in 2023, notably lower than in 2013 when 72% of Americans reported that religion was the most important thing in their lives (27%) or one among many important things (45%). In contrast, a plurality of Americans (45%) say that religion is not as important as other things (19%) or religion is not important at all in their life (26%) in 2023, nearly twice what it was a decade ago when over one in four Americans (27%) reported religion was not as important (14%) or not important at all (13%).

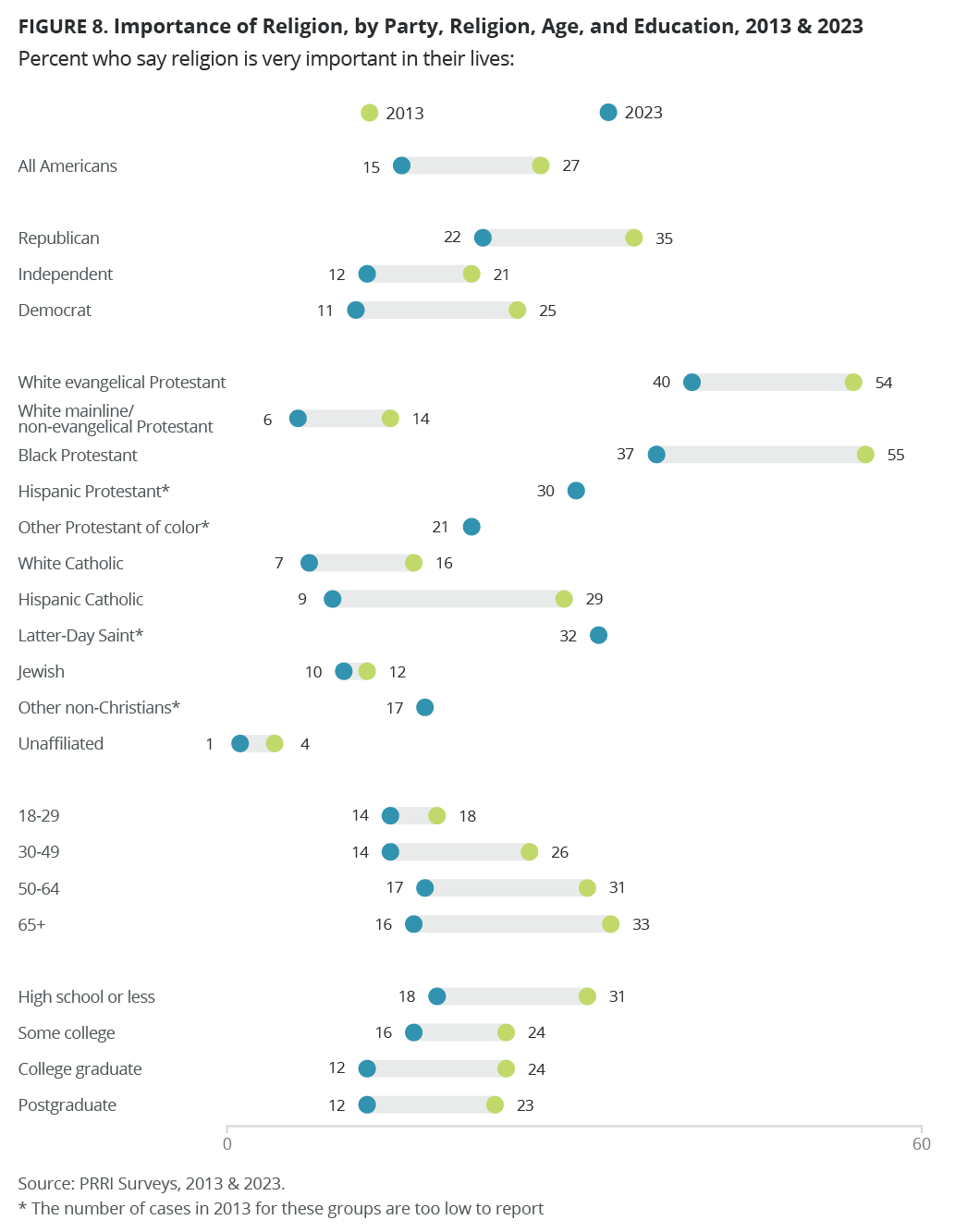

Isolating our analysis to those Americans who express the greatest religious saliency, Republicans (22%) are twice as likely as independents (12%) and Democrats (11%) to report religion as the most important thing in their lives in 2023. However, all partisans were less likely to do so in 2013, when 35% of Republicans, 25% of Democrats, and 21% of independents reported religion as the most important part of their lives.

White evangelical Protestants (40%), Black Protestants (37%), Latter-day Saints (32%), and Hispanic Protestants (30%) are most likely to report religion as the most important thing in their lives, compared with other Protestants of color (21%), other non-Christians (17%), Jewish Americans (10%), Hispanic Catholics (9%), white Catholics (7%), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (6%) who are the least likely to report the same. Unsurprisingly, just 1% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say the same. Black Protestants (55% in 2013) and Hispanic Catholics (29% in 2013) were substantially more likely to report, by about 20 percentage points more, that religion is the most important in their lives. White evangelical Protestants (54% in 2013) and white Catholics (16% in 2013) were also more likely to report the same in 2013.[6]

The importance of religion has also decreased across all age groups and education levels over the past decade. The biggest decline in the importance of religion emerges among senior Americans 65 and over (from 33% to 16%), followed by Americans ages 50-64 (from 31% to 17%) and Americans ages 30-49 (from 26% to 14%). There are no meaningful changes in the importance of religion among young Americans under 30 (from 18% to 14%).

Americans across all education levels are less likely to report that religion is the most important thing in their lives in 2023, compared with 2013: Americans with a high school education or less (from 31% to 18%), with some college education (from 24% to 16%), with a college degree (from 24% to 12%), and with a postgraduate degree (from 23% to 12%).

Church Attendance

Americans have grown less likely to attend church services over the past decade. In 2023, nearly one-quarter of Americans (24%) attend religious services either virtually or in person at least once a week, a 7 percentage point decline from 31% in 2013. Similarly, around two in ten Americans (21%) say they attend church services once or twice a month or a few times a year in 2023, a decline of 4 percentage points from 25% in 2013. By contrast, Americans who seldom or never attend religious services show the most substantial shifts over the past decade. The majority of Americans (54%) report seldom or never attending church services in 2023, compared with roughly four in ten Americans (43%) in 2013.

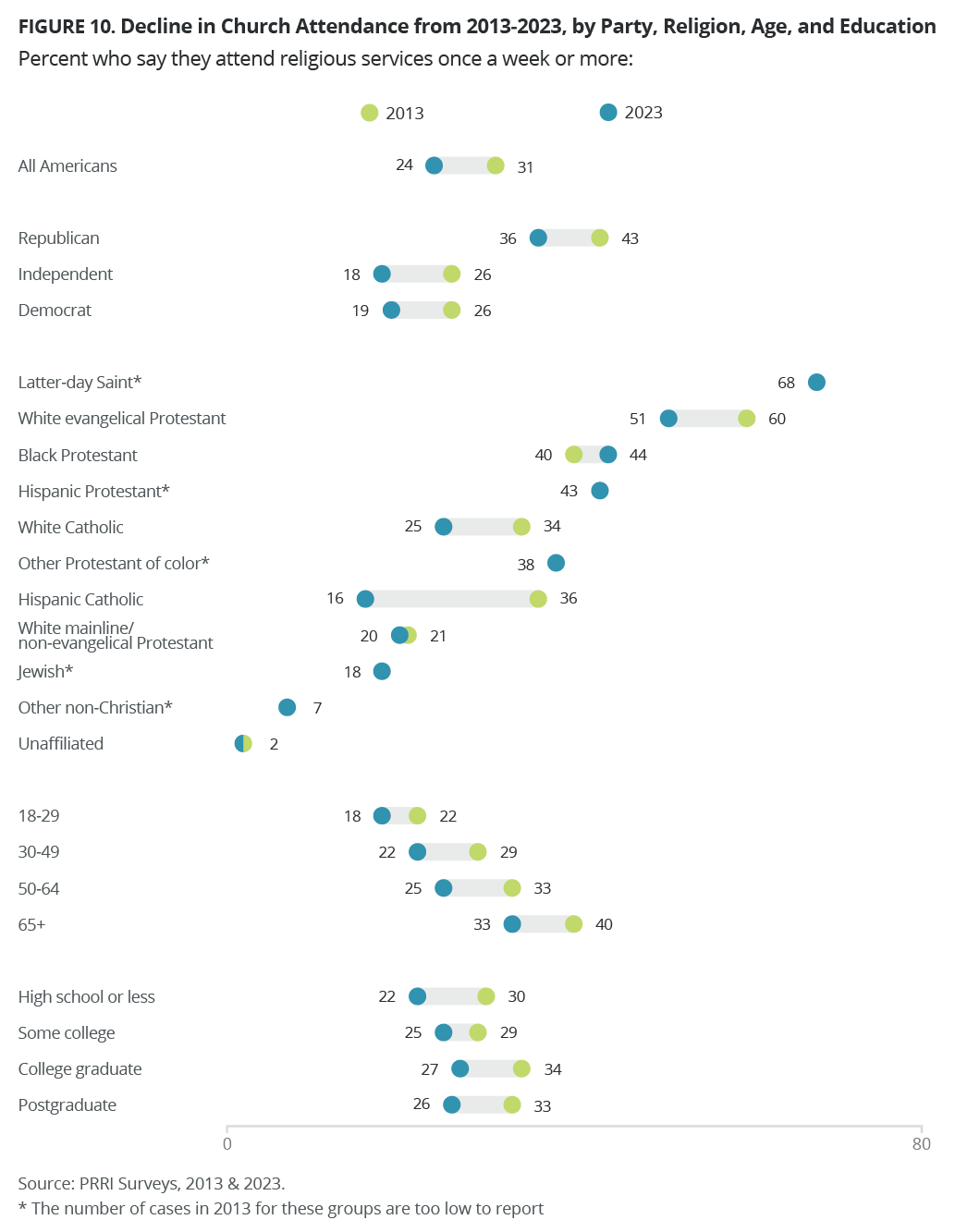

Among partisans, Republicans (36%) are more likely than independents (18%) and Democrats (19%) to report attending services at least once a week. Higher proportions of each partisan group attended religious services more frequently in 2013, including 43% of Republicans, 26% of independents, and 26% of Democrats.

Latter-day Saints (68%) and white evangelical Protestants (51%) are the only religious groups whose majorities say they attend church services at least once a week. A plurality of Black Protestants (44%), Hispanic Protestants (43%), and other Protestants of color (38%) also attend church services weekly. One-fourth of white Catholics (25%); around two in ten white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (20%), Jewish (18%), and Hispanic Catholics (16%); and only 7% of other non-Christians say they attend church services at least once a week.

Frequent church attendance has decreased dramatically among religious traditions from 2013 to 2023, including white evangelical Protestants (60% to 51%), white Catholics (34% to 25%), and Hispanic Catholics (36% to 16%). Unsurprisingly, very few religiously unaffiliated Americans (2%) attend church services at least once a week.[7]

Seniors over the age of 65 (33%) are more likely than younger age groups, including 25% of Americans between 50 and 64, 22% of Americans between 30 and 49, and 18% of young Americans under 30, to say they attend church weekly or more. Older age groups, however, have seen more of a decrease in frequent church attendance than younger age groups over the past decade. In 2013, four in ten seniors over the age of 65 (40%) and 33% of Americans between 50 and 64 attended church weekly, compared with 29% of Americans 30-49 and 22% of young Americans under 30.

Americans with a postgraduate education (33% in 2013 vs. 26% in 2023), a college education (34% in 2013 vs. 27% in 2023), and those with a high school education (30% in 2013 vs. 22% in 2023) are less likely to attend religious services at least once a week now than they were a decade ago. There are no differences in religious attendance among Americans with some college (29% in 2013 vs. 25% in 2023).

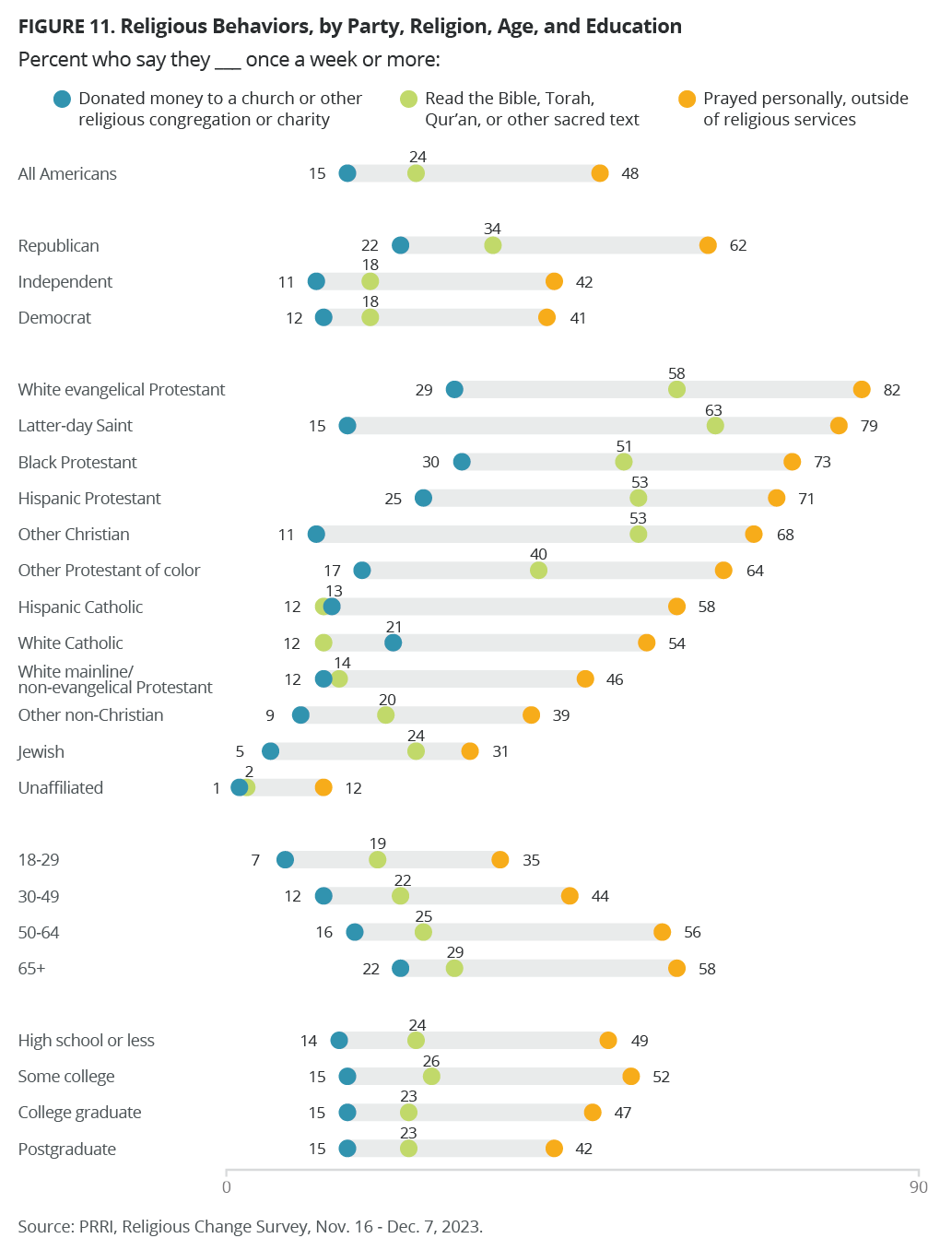

Prayer

Nearly half of Americans (48%) say they pray personally, outside of religious services, at least once a week. Less than two in ten Americans (16%) say they pray at least a few times a year and around one-third say they seldom or never pray (34%). The majority of Republicans (62%) report praying at least once a week, compared with 42% of independents and 41% of Democrats.

With the exception of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (46%), the majority of each Christian tradition say they pray at least once a week: white evangelical Protestants (82%), Latter-day Saints (79%), Black Protestants (73%), Hispanic Protestants (71%), Protestants of color (64%), Hispanic Catholics (58%), and white Catholics (54%). A plurality of other non-Christians (39%), 31% of Jewish Americans, and just 12% of unaffiliated Americans say they personally pray at least once a week.

The majority of senior Americans 65 or over (58%) and Americans ages 50-64 (56%) say they pray at least once a week, compared with 44% of Americans ages 30-49 and 35% of young Americans under 30.

Americans with postgraduate degrees (42%) are less likely to report praying frequently than Americans with a high school education (49%) and those with some college education (52%) but are not significantly different from Americans with a college degree (47%).

Reading Religious Texts

Around one-quarter of Americans (24%) say they read the Bible, Torah, Quran, or other sacred text once a week or more, and less than two in ten Americans (17%) read a religious text once or twice a month or at least a few times a year. Nearly six in ten Americans (58%) seldom or never read religious texts. Republicans (34%) are more likely than independents (18%) or Democrats (18%) to read religious texts at least once a week.

The majority of Latter-day Saints (63%), white evangelical Protestants (58%), Hispanic Protestants (53%), and Black Protestants (51%) report reading religious texts once a week or more. Forty percent of other Protestants of color, 24% of Jewish Americans, and 20% of other non-Christians also read religious texts weekly, while only 14% of white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants and 12% of white Catholics and Hispanic Catholics say the same. Just 2% of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they read religious texts once a week or more.

Americans 65 or over (29%) are notably more likely than Americans ages 50-64 (25%), ages 30-49 (22%) and Americans under 30 (19%) to say they read the Bible, Torah, Quran, or other sacred texts once a week or more.

Donating to Religious Organizations

Less than two in ten Americans (15%) say they donate money to a church or other religious congregation or charity once a week or more. One-quarter of Americans (26%) donate once or twice a month or a few times a year, and a majority of Americans (58%) seldom or never donate to a church or other religious organization. Republicans (22%) are twice as likely as Democrats (12%) and independents (11%) to donate to a church at least once a week.

Roughly one in four followers of many Christian religious traditions donate to a church once a week or more, including 30% of Black Protestants, 29% of white evangelical Protestants, 25% of Hispanic Protestants, and 21% of white Catholics. Among Christian groups, Protestants of color (17%), Latter-day Saints (15%), Hispanic Catholics (13%), and white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (12%) are the less likely to report donating to a church at least once a week as are other non-Christians (9%) and Jewish Americans (5%). Unsurprisingly, just 1% of religiously unaffiliated say they donate to a church or other religious organization at least once a week.

Donating weekly to a church or other religious congregation or charity decreases as age decreases: 22% of seniors 65 or over, 16% of Americans ages 50-64, 12% of Americans ages 30-49, and 7% of Americans under 30. There is little difference by education levels.

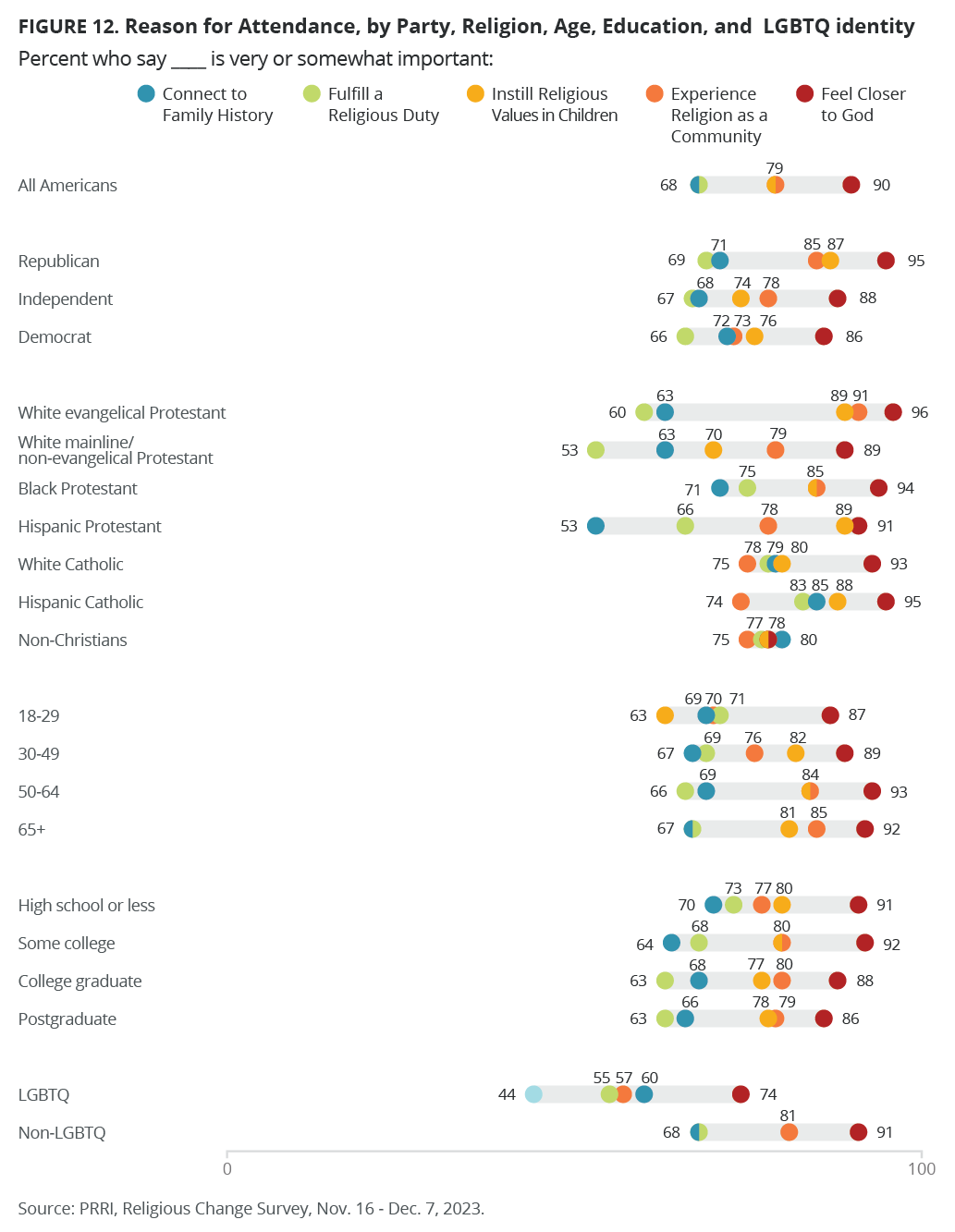

Why Americans Attend Religious Services

Among Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year, solid majorities report feeling closer to God (90%), experiencing religion in a community (79%), and instilling values in their children (79%) as very or somewhat important reasons for their personal attendance. Americans are less likely to report attending to fulfill a duty (68%) or because of a family tradition (68%) as very or somewhat important reasons.

Feeling Closer to God, Experiencing Religion, and Instilling Religious Values in Children

Among Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year, solid majorities across party, religion, age, and education report feeling closer to God, experiencing religion as a community, and instilling religious values in children as very or somewhat important reasons why they attend services. Even among young American attenders under 30, a majority name those three as reasons why they attend religious services (87%, 70%, and 63%, respectively). LGBTQ church attenders are notably less likely to report feeling closer to God than non-LGBTQ church attenders (91% vs. 74%).

Fulfill a Duty and Connect to Family History

Among Americans who attend religious services, there are no differences among partisans. Around seven in ten Republicans (69% and 71%), independents (67% and 68%), and Democrats (66% and 72%) say a very or somewhat important reason for attending religious services is to fulfill a religious duty or obligation and to connect to family history.

Similarly, roughly eight in ten Hispanic Catholics (83% and 85%), white Catholics (78% and 79%), and members of non-Christian religions (77% and 80%) report that very or somewhat important reasons for attending religious services are to fulfill a religious duty or obligation and to connect to family history. Except for Black Protestants (75% and 71%), fewer Protestants report both as reasons for attending religious services, including six in ten or fewer Hispanic Protestants (66% and 53%) and white evangelical Protestants (60% and 63%). For white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants, connecting to family history (63%) is more important than fulfilling a religious duty (53%).

There are little differences by age. About seven in ten Americans across age groups name both as important reasons why they attend religious services. Among Americans with a high school degree or less who attend religious services, 73% name fulfilling a religious duty as important, compared with 68% of Americans with some college, and 63% of those with a college education and postgraduate education. However, there are little differences among Americans with a high school education (70%), a college degree (68%), a postgraduate degree (66%), and those with some college education (64%) who attend religious services to connect to family history.

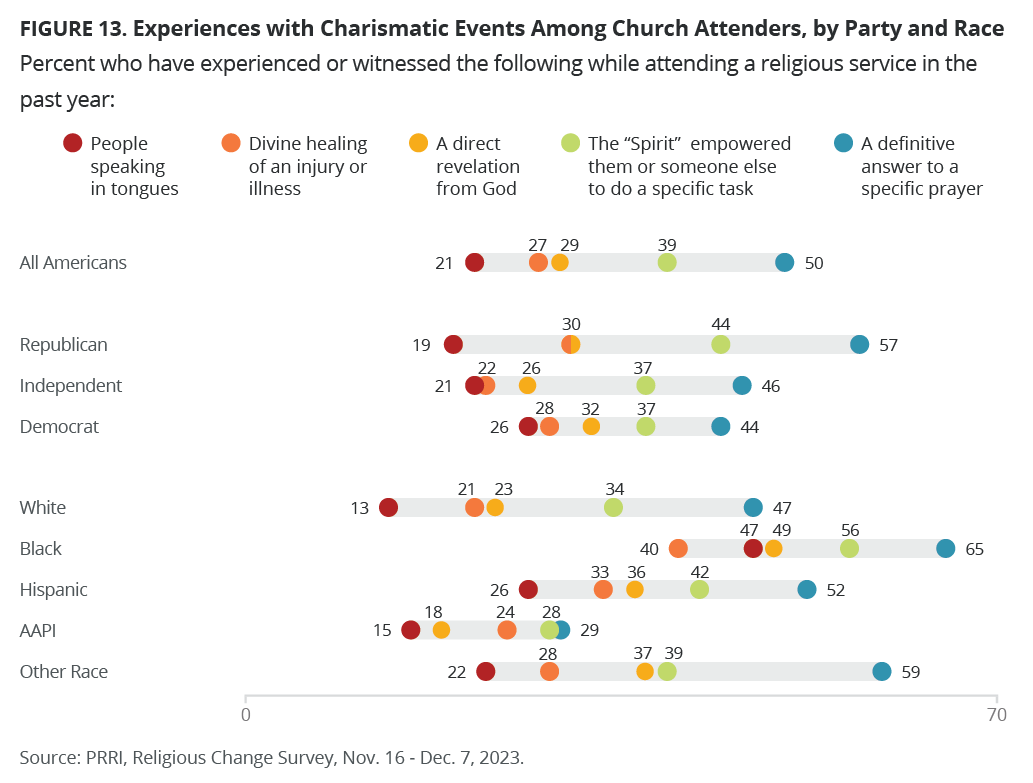

Charismatic Elements in Churches

Christian religious practices that emphasize the work of the Holy Spirit and spiritual gifts, such as faith healing and speaking in tongues, have their earliest roots in Pentecostal denominations formed around the turn of the last century, such as the Assemblies of God and the Church of God in Christ. In the late 1950s, these distinctive Pentecostal worship behaviors crossed over into some mainline Protestant denominations, Catholic churches, and Orthodox churches as part of a larger charismatic movement.[8] We asked Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year whether they have experienced themselves, or witnessed, numerous charismatic elements while attending a religious service in the past year to gauge how prevalent such practices are among Americans today.

Among such American churchgoers, half say they have received a definitive answer to a specific prayer while attending a religious service in the past year (50%). Nearly four in ten church attenders say the “Spirit” has empowered them or someone else to do a specific task (39%). Around three in ten say they have received a direct revelation from God (29%) or have witnessed divine healing of an injury or illness (27%) and roughly two in ten have seen people speaking in tongues (21%) in the past year at religious services.

Among church attenders, Republicans are more likely than independents and Democrats to say they have received a definitive answer to a specific prayer (57% vs. 46% and 44%, respectively) and that the “Spirit” empowered them or someone else to do a specific task (44% vs. 37% both). By contrast, Democrats (26%) are more likely than Republicans (19%) to have witnessed people speaking in tongues, but do not differ meaningfully from independents (21%). Republicans (30%) and Democrats (28%) are more likely than independents (22%) to say they witnessed divine healing of an injury or illness. There are no differences by partisan churchgoers who have received a direct revelation from God.

Black churchgoers are consistently more likely than white, Hispanic, AAPI, and other race churchgoers to report experiences with all charismatic events.

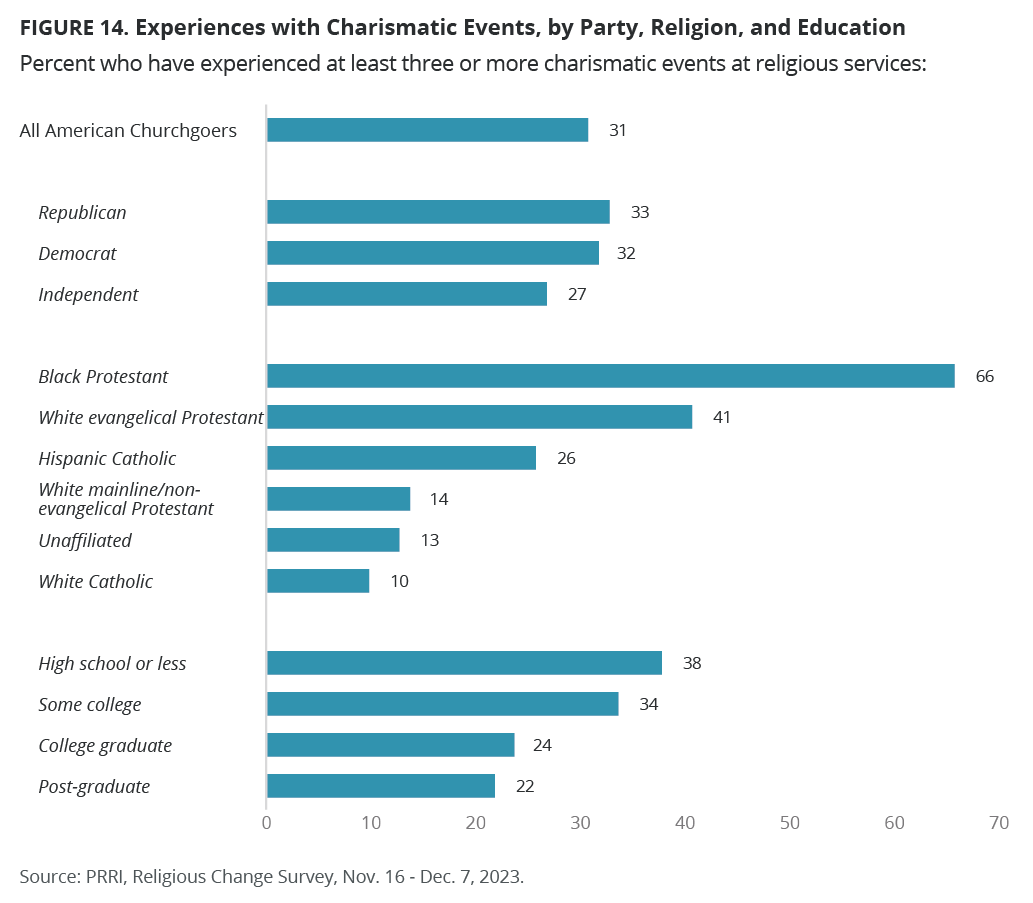

When adding those experiences together, we find that, on average, regular church attenders report experiencing or witnessing 1.7 charismatic elements while attending a religious service in the past year.[9] More than one-third of church attenders (36%) have not experienced any charismatic events while attending church services. Another one-third of attenders (33%) have experienced one or two events and 31% have experienced three or more events.[10]

Isolating our analysis to American churchgoers who report experiencing at least three or more charismatic events, we find no differences among Republicans (33%) and Democrats (32%), though independents (27%) are less likely to have experienced at least three charismatic events during religious services in the past year.

Black Protestants are far more likely than other religious Americans to worship in churches characterized by spirit-filled practices. Two-thirds (66%) of Black Protestant churchgoers report experiencing at least three charismatic events while at church in the past year. Experience with spirit-filled practices is also not uncommon among white evangelical Protestant church attenders (41%). Fewer Hispanic Catholic (26%), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestant (14%), and white Catholic church attenders (10%) report experiencing at least three charismatic events in the past year during religious services.

Church attenders without a college degree (36%) are more likely than those with a college degree (23%) to say they have witnessed three or more charismatic events at their religious services.

Prophetic and Prosperity Theological Beliefs

While our previous section considered the extent to which churchgoers experience or witness charismatic practices during worship, many Americans also hold theological beliefs rooted in prophecy as well as the prosperity gospel, both of which have ties to American Pentecostalism. The prosperity gospel, first popularized by televangelists such as the late Oral Roberts, holds that there is a connection between one’s devotion to God and financial success and good health.

Specifically, over four in ten Americans agree that “God reveals his plans for the future to humans as a prophecy” (45%). Roughly one-third of Americans agree with the statements that “God has given some people the power to heal others through prayer and the ‘laying on of hand’” (36%), “modern-day prophets continue to reveal God’s plan to humanity” (31%), and “God always rewards those who have good faith with good health, financial success, and fulfilling personal relationships” (31%). Across all these theological beliefs measures, Republicans are more likely than independents and Democrats to agree. Similarly, Black Americans tend to agree more with all these theological beliefs than white, Hispanic, AAPI, and other race Americans.

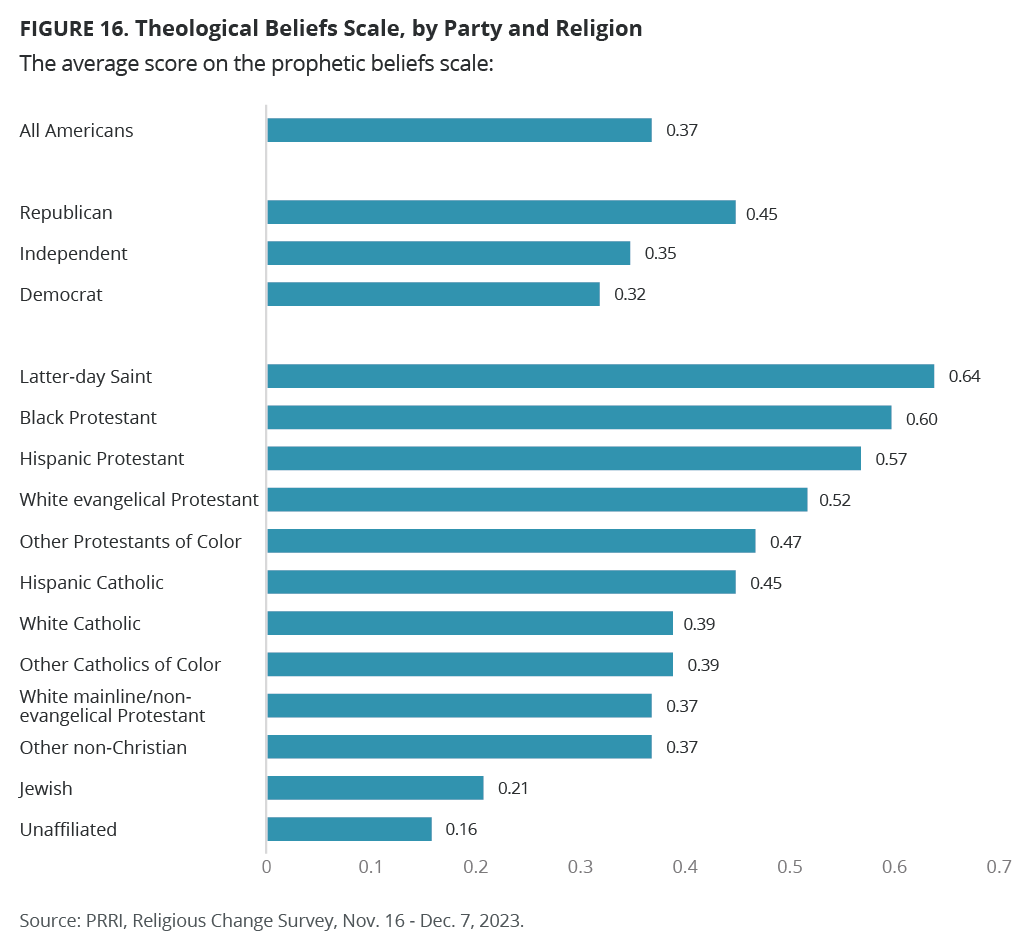

Developing a Prophetic and Prosperity Theological Beliefs Scale

To better understand which groups are more likely to believe in these theological concepts, PRRI developed an additive scale that combines the four aforementioned beliefs, normalizing their values to a score between 0 and 1. A score of 0 indicates strong disagreement to every belief, while a score of 1 indicates strong agreement for every belief. Examining mean scores for different demographic groups allows us to directly compare how likely Americans from a given group are to believe in these ideas.[11]

There are significant partisan differences among Americans with respect to prophetic and prosperity beliefs. Republicans (0.45) score higher on the prophetic beliefs scale than all Americans (0.37), independents (0.35) or Democrats (0.32). Significant racial differences also emerge on these beliefs, with Black (0.54) and Hispanic Americans (0.43) scoring higher on the scale than multiracial (0.36), white (0.33), and AAPI Americans (0.31).

Members of some religious affiliations score much higher on the prophetic and prosperity beliefs scale, especially Latter-day Saints (0.64) and Black Protestants (0.6), who score the highest among religious traditions. Hispanic Protestants (0.57), white evangelical Protestants (0.52), other Protestants of color (0.47), and Hispanic Catholics (0.45) score around the middle of the scale. White Catholics (0.39), other non-white Catholics (0.39), white mainline/non-evangelical Protestants (0.37), and other non-Christians (0.37) share a similar score on the prophetic scale. Jewish Americans (0.21) and religiously unaffiliated Americans (0.16) score the lowest on the scale.

Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, those who identify as nothing in particular (0.20) are more than twice as likely as those who identify as agnostic (0.1) or atheist (0.05) to score higher on the prophetic beliefs scale.

Religion and the MAGA Movement

The Role of Charismatic Christianity in the Republican Party

When the Christian Right first emerged as a major influence within the Republican Party starting in the late 1970s, charismatic elements and views about prophecy or the prosperity gospel did not play an outsized role among its leaders. It was not until the late televangelist Pat Robertson, an independent Baptist minister with strong ties to Pentecostal and charismatic Christians, unsuccessfully sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1988 that American Pentecostal-charismatics were more welcomed into the GOP’s religious tent. Former President Donald Trump has spent more time than any previous Republican president cultivating support among prominent Pentecostal-charismatic leaders.[12] Retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn, a former, if short-lived, national security advisor to Trump, helped launch the ReAwaken America Tour in 2021, a Christian nationalist grassroots organization that often holds events in prominent Pentecostal churches.

Our survey allows us to take a deeper dive into the extent to which Republicans are attending religious services marked by charismatic experiences, as well as the prevalence of prophecy and prosperity gospel views among Americans who are part of the GOP.

Approximately one-third of Republicans who attend church at least a few times a year indicated that they attended a religious service where they had experienced themselves, or witnessed, at least three charismatic elements. However, just 19% of Republicans overall, which includes Republicans who rarely, if ever attend church, have experienced such charismatic elements in the past year, showing that such experiences are relatively uncommon among rank-and-file Republicans nationally.

There is also little support for the idea that Republican churchgoers who view Trump favorably are more likely to experience charismatic religious practices on a regular basis (35%) compared with those Republican churchgoers who view Trump unfavorably (39%). Expanding the lens to all Republicans, just one in five Republicans with favorable views of Trump experience high levels of charismatic religious practice (19%), largely similar to those Republicans nationally who view Trump unfavorably (18%). In other words, charismatic Christians make up a relatively small portion of Republicans who view Trump favorably.

While 37% of Republican churchgoers who most trust Fox News report having had at least three charismatic experiences at church in the past year, this percentage is not significantly higher than Republican churchgoers who trust other media sources. Republicans who most trust Fox News or far-right news and who experience charismatic elements at religious services regularly make up around just 20% of Republicans nationally.

Republican church attenders who qualify as Christian nationalism Adherents and Sympathizers, however, are more significantly likely than those who qualify as Skeptics and Rejecters to have witnessed or experienced at least three charismatic events in the past year. Yet, charismatic Christian nationalism Adherents and Sympathizers make up roughly one in four Americans who identify as Republican.

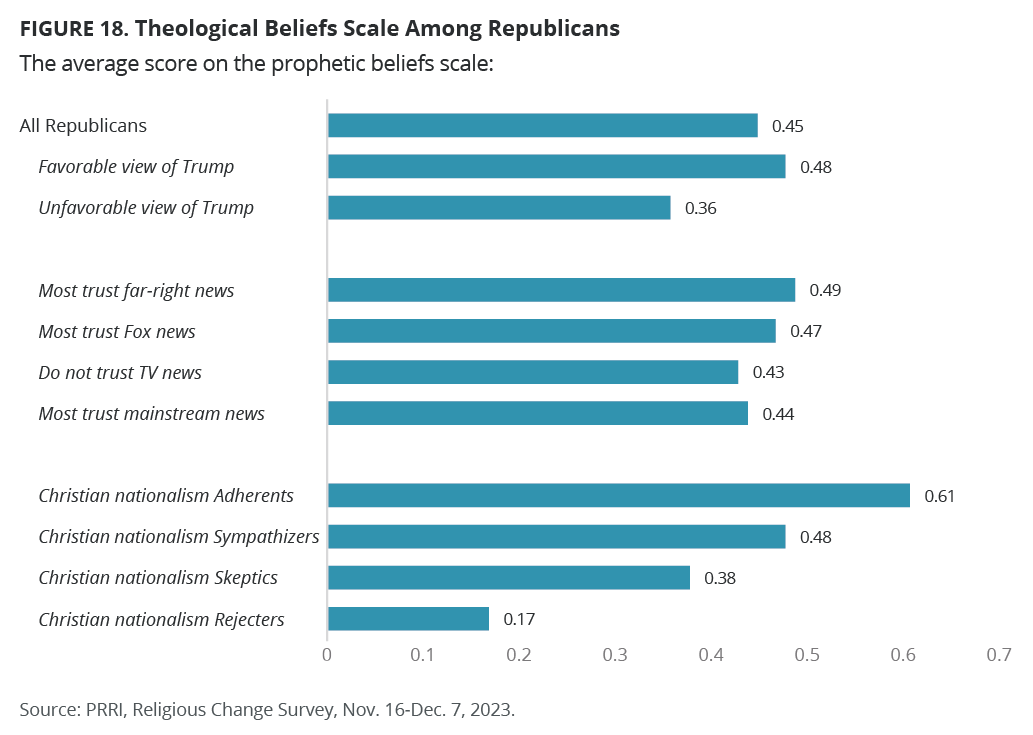

Turning away from experiences in church, however, we find that Republicans who hold a favorable view of Trump score higher on the prophetic and prophecy belief scale.

Among Republicans, those with a favorable view of Trump (0.48) score higher on the prophetic beliefs scale than those with an unfavorable view of Trump (0.36). Similarly, Republican Christian nationalism Adherents (0.61) and Sympathizers (0.48) score substantially higher on the prophetic beliefs scale than Skeptics (0.38) and Rejecters (0.17). However, Republicans’ belief in the prophecy and the prosperity gospel is largely unlinked to whether they view far-right news outlets or Fox News.

Survey Methodology

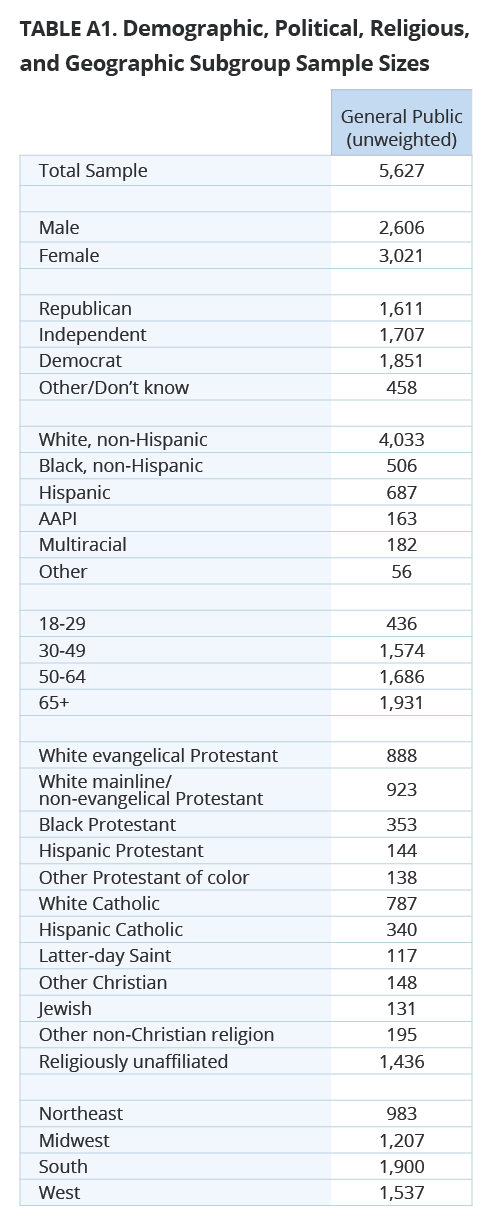

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. The survey was carried out among a representative sample of 5,627 participants (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Among those, 5,303 are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 324 were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Interviews were conducted online between November 16 and December 7, 2023.

Respondents are recruited to the Knowledge-Panel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS—a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

The initial sample drawn from the Knowledge-Panel was adjusted using pre-stratification weights so that it approximates the adult U.S. population defined by the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey. Next, a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling scheme was used to select a representative sample.

To reduce the effects of any non-response bias, a post-stratification adjustment was applied based on demographic distributions from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS). The post-stratification weight rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, Census division, metro area, education, and income. The sample weighting was accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights were trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results. In addition to an overall national weight, separate weights were computed for each state to ensure that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. The state-level post-stratification weights rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, and income.

The margin of error for the national survey is +/- 1.79 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence, including the design effect for the survey of 1.88. In addition to sampling error, surveys may also be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects. Additional details about the Knowledge Panel can be found on the Ipsos website: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solution/knowledgepanel.

[1] Robert Putnam and David Campbell estimated the rate of religious switching to be between 35 and 40% of the United States population. See Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell. “American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us.” New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

[2] Ex-Catholics who now identify with other Christian religions include Jehovah’s Witnesses (2%), Black Protestants (2%), and Latter-day Saints (2%). Ex-Catholics who now identify as non-Christians include Unitarian Universalists (1%), Buddhists (1%), Jewish Americans (1%), and other non-Christian religions (2%).

[3] Catholics of all races are combined as the numbers of cases for white, Hispanic, and other Catholics of color are too small to report separately (N=77).

[4] This statement wasn’t asked in 2016. PRRI asked “a traumatic event in your life” and 18% of unaffiliated Americans noted this reason then.

[5] The number of cases for Black unaffiliated and other unaffiliated of color is too low to report.

[6] The numbers of cases for Latter-day Saints, Hispanic Protestants, other Protestants of color, and Jewish Americans in 2013 are too small to report.

[7] The number of cases for other religious groups who report attending religious services at least once a week for 2013 is too small to report.

[8] For more on the history of this movement, see Roger G. Robins, Pentecostalism in America. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2010.

[9] Factor analysis shows that all these five items load on one dimension.

[10]About 13% of church attenders experienced three out of five charismatic events, 9% experienced four out of five charismatic events, and 9% experienced all five charismatic events.

[11] Respondents’ answers across all four questions are highly correlated, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, indicating a high degree of reliability for the scale.

[12] Particularly those who strongly tout the prosperity gospel, such as Paula White-Cain, Mark Burns, and Kenneth Copeland.

Acknowledgments

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. We would like to thank Drs. Fanhao Nie, Flavio Rogerio Hickel Jr., Leah Payne, and Tarah Williams for their help in drafting the questions about charismatic experiences used in the survey.