To view a PDF of slides presented at the September 28, 2022, livestreamed presentation of the report, click here: Creating More Inclusive Public Spaces: Structural Racism, Confederate Memorials, and Building for the Future. To view a replay of the webinar via YouTube, click here: New Survey Release: The Role of Religion in Creating More Inclusive Public Spaces.

Structural Racism and Discrimination in America

Across the United States over the past decade, there have been heated discussions about Confederate statues and memorials in public spaces. Some cities have removed statues or renamed public spaces memorializing the Confederacy and Confederate leaders, while others remain embroiled in debate. This survey, conducted jointly by PRRI and E Pluribus Unum, examines the role of race and racism in how Americans view Confederate monuments, as well as American attitudes toward creating making public spaces more inclusive.

The Structural Racism Index

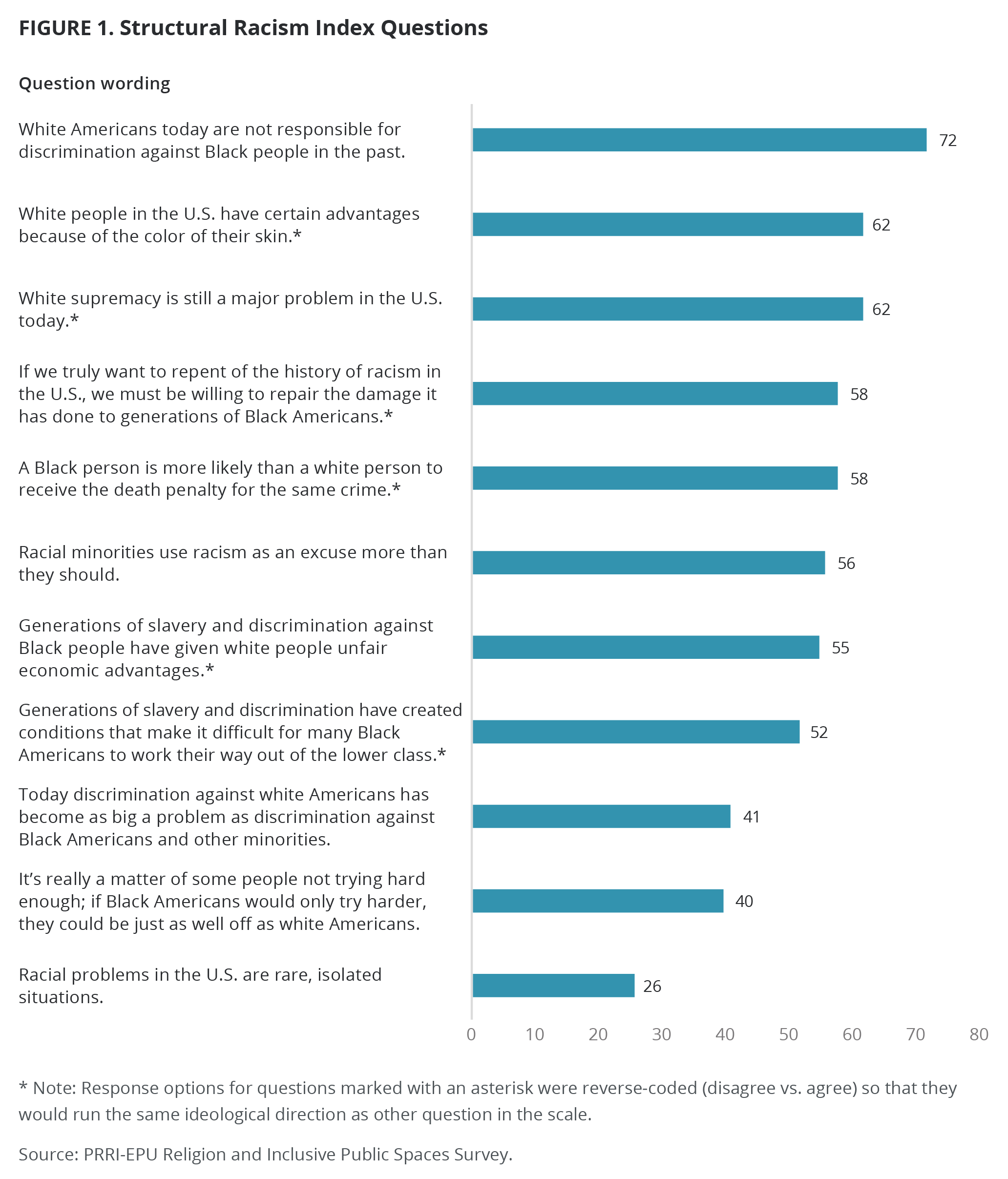

In order to measure Americans’ views on race and structural racism, PRRI asked 11 questions on a range of topics.[1] These questions cover a lot of ground: attitudes about white supremacy and racial inequality, the impact of discrimination on African American economic mobility, the treatment of African Americans in the criminal justice system, general perceptions of race, and whether racism is still significant problem today. The answers across all 11 questions, which are highly correlated, were combined to create a “Structural Racism Index” scale.

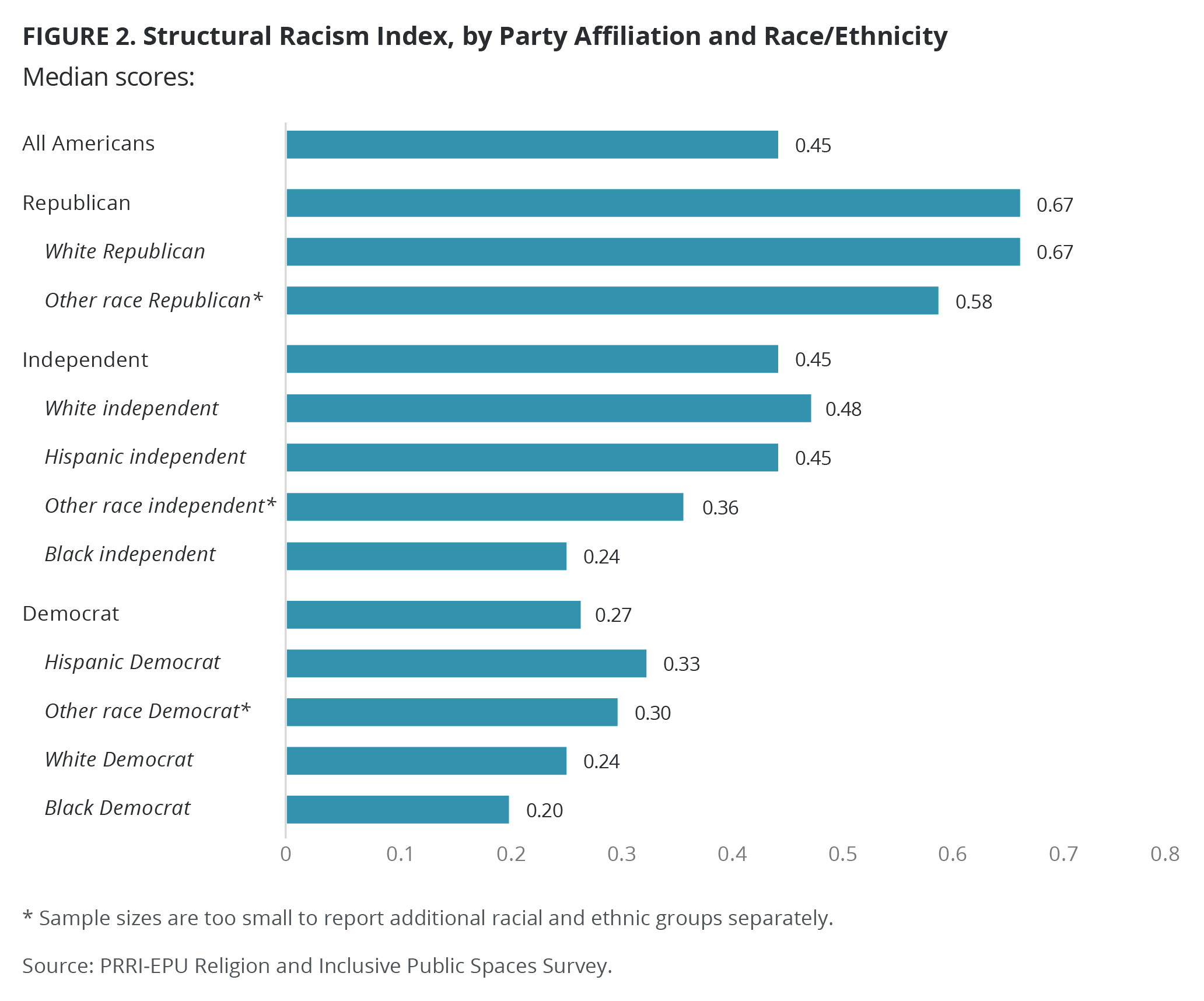

The structural racism index combines answers to these questions and rescales the scores to values from 0 (low) to 1 (high). Among all Americans, the median value on the structural racism index is 0.45, near the center of the scale.

The median score on the structural racism index for Republicans is 0.67, compared with 0.45 for independents and 0.27 for Democrats. By race, white Republicans score 0.67 and Republicans of other races score 0.58. Scores among white independents and white Democrats are much lower (0.48 and 0.24, respectively). Black, Hispanic, and Democrats of all other races also hold relatively low scores on the structural racism index (0.20. 0.33, and 0.30, respectively).

By race and ethnicity, white Americans are the most likely to score high on the structural racism index, with a median score of 0.52. Hispanic Americans have a median score of 0.42, closely followed by multiracial Americans at 0.30 and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) at 0.39. Black Americans have the lowest median score, at 0.24.

White Americans are divided by education, with a median score of 0.58 among those who do not have a four-year college degree and 0.39 among those who have a four-year degree or higher. White Americans under the age of 50 have a lower median score than those over 50 (0.48 vs. 0.55).

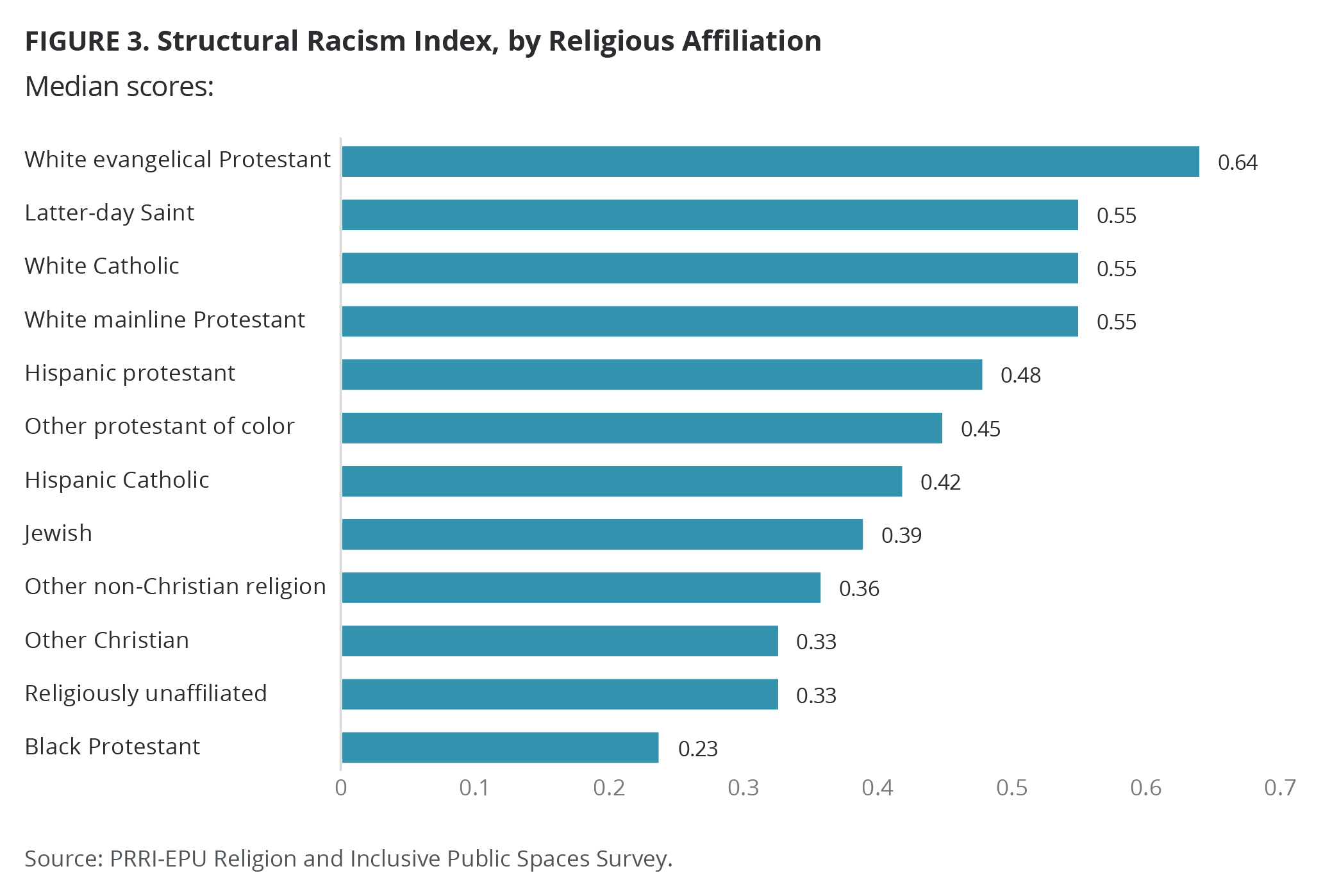

Predominantly white religious groups score highest on the structural racism scale. White evangelical Protestants have the highest median score, at 0.64, while Latter-day Saints, white Catholics, and white mainline Protestants each have a median of 0.55. By contrast, religiously unaffiliated white Americans score 0.33.

Other Protestants of color — those who are not white, Black, or Hispanic — score near the median for all Americans, at 0.45, as do Hispanic Protestants (0.48) and Hispanic Catholics (0.42). Jewish Americans (0.39), other non-Christian religious Americans (0.36), other Christians, who are mostly composed of Jehovah’s Witnesses and Orthodox Christians (0.33), and all religiously unaffiliated Americans (0.33) fall significantly below the national median. Black Protestants score lowest, with a median of 0.26.

Americans’ Experiences with Discrimination

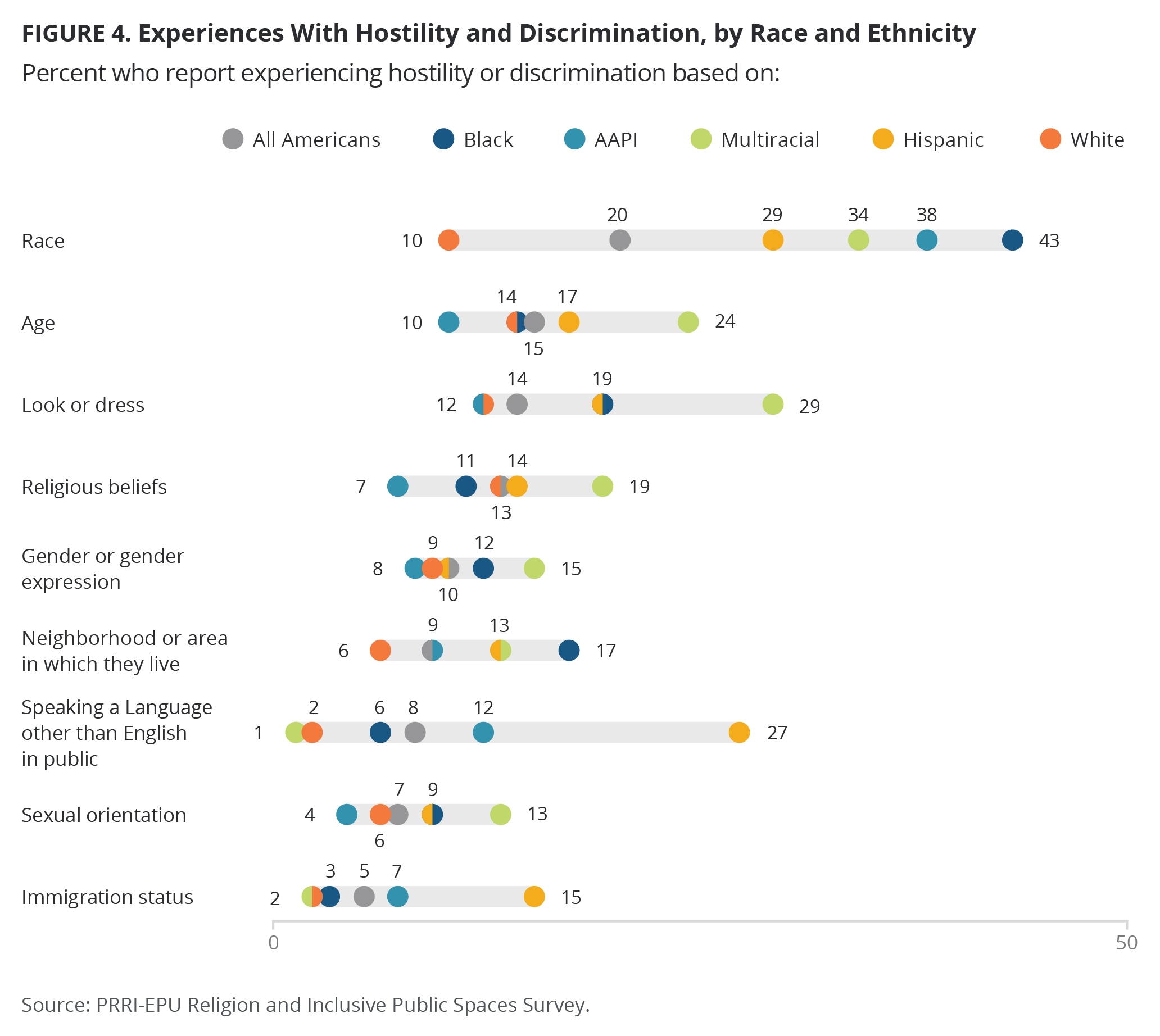

PRRI asked respondents a series of questions about whether they had personally experienced various types of hostility or discrimination during the past few years. Around six in ten Americans (62%) did not report discrimination in any of the prompted categories. White Americans were least likely to report experiencing discrimination in most categories, while substantial portions of Black (43%), AAPI (38%), multiracial (34%), and Hispanic Americans (29%) report experiences with race-based discrimination. Smaller, but meaningful, shares of Americans report other forms of discrimination.

Young Americans in the 18-29 age group are most likely to say they have faced age-based discrimination or hostility (20%), compared with 12% of those ages 30-49, 15% of those ages 50-64, and 14% of those age 65 and over.

More than one in ten Americans (13%) report experiencing discrimination or hostility based on their religious beliefs. Latter-day Saints (43%) and Jewish Americans (33%) were the most likely to experience discrimination of this kind. Nearly one in five white evangelical Protestants (19%) reported experiencing discrimination based on their religious beliefs, along with 17% of Hispanic Protestants, 16% of those belonging to a non-Christian religion other than Judaism, 12% of Black Protestants, and 12% of those following another Christian religion. Around one in ten other Protestants of color (11%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (11%), white Catholics (10%), and Hispanic Catholics (9%) say they have experienced religion-based discrimination. White mainline Protestants (7%) are the least likely to say they have experienced this.

Those who report making less than $25,000 per year are most likely to say they have faced discrimination or hostility because of where they live (21%). Less than one in ten of any other income group report this type of discrimination.

The 'Lost Cause,’ Confederate Memorials, and ‘Southern Pride’

Awareness of ‘Lost Cause’ Symbols and Confederate Memorials

Confederate Flag Displays

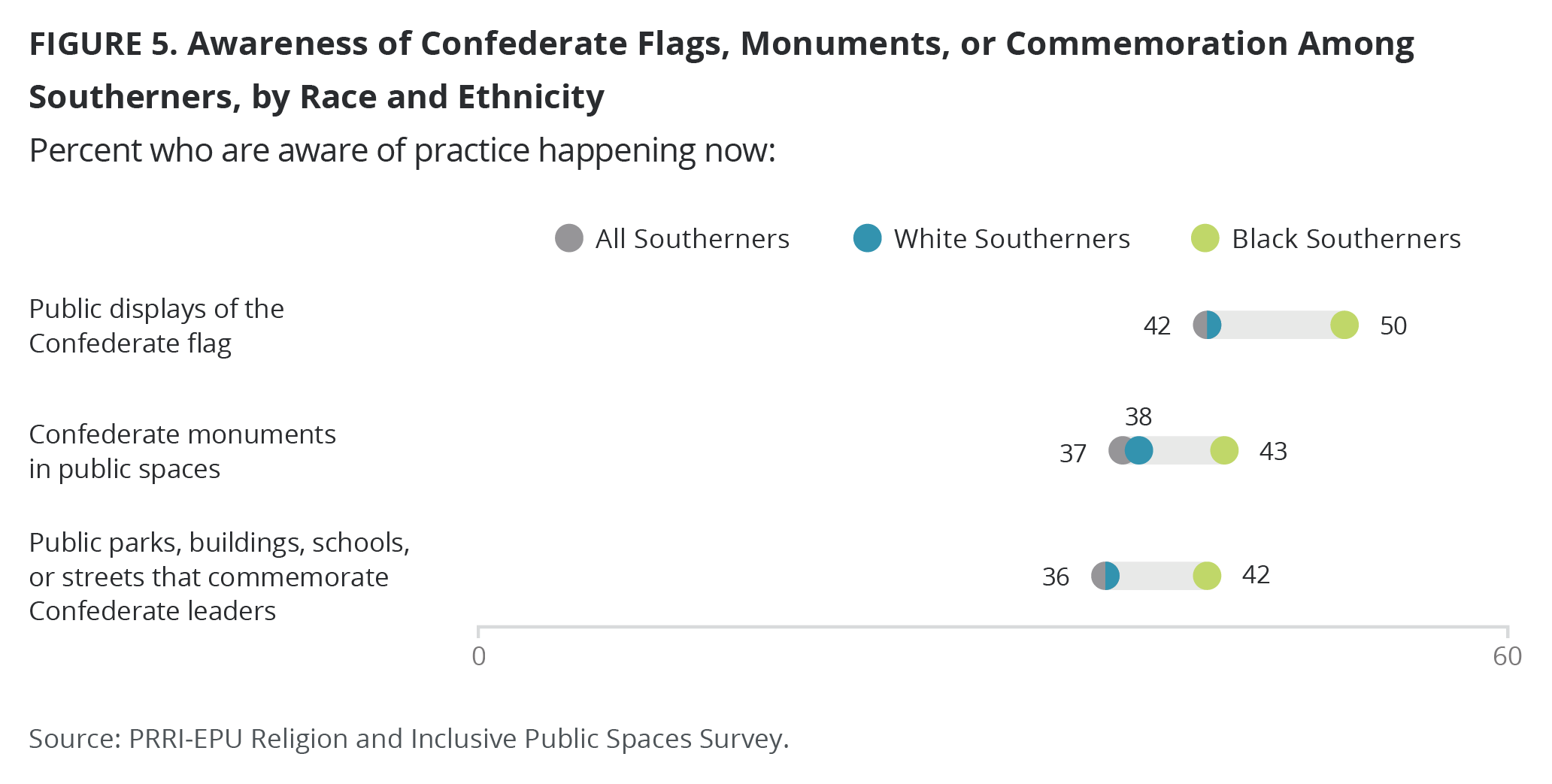

About three in ten Americans (29%) say they are aware of public displays of the Confederate flag in their community right now. One in four say there were displays of Confederate flags in their community in the past but not anymore (24%), and 44% say there have never been displays of Confederate flags in their community. Unsurprisingly, residents of Southern states (42%) are more likely than those in the rest of the country (22%) to report that there are current displays of the Confederate flag in their community.[2]

More Democrats (34%) and independents (29%) than Republicans (24%) say they are aware of Confederate flag displays in their community right now. Republicans (28%) are more likely than independents (24%) and Democrats (21%) to say these displays existed in the past but not anymore. The plurality of all partisan groups say Confederate flag displays never existed in their community, including 42% of Democrats, 45% of independents, and 45% of Republicans. Even in the South, Republicans are less likely than Democrats to say they are aware of Confederate flag displays currently in their community (35% vs 49%).

Black Americans (41%) and multiracial Americans (40%) are more likely than Hispanic Americans (28%), white Americans (27%), or AAPI (23%) to say they are aware of Confederate flags in their community right now. Even in the South, these patterns hold, with Black Southerners significantly more likely than white Southerners to say they are aware of Confederate flags currently on display in their community (50% vs. 42%).

Confederate Monuments

About one in five Americans (22%) say that they are aware of Confederate monuments in public spaces in their community right now, while an additional 22% say there were such monuments in the past, and 52% say there never have been. Residents of the South (37%) are more than twice as likely as those elsewhere (14%) to say there are currently Confederate monuments in their community.

There are no partisan differences in awareness of Confederate monuments in local communities right now, as 24% of Democrats, 22% of independents, and 22% of Republicans report these monuments currently exist. Democrats (22%) and Republicans (23%) are more likely than independents (19%) to say these displays used to exist but don’t anymore, and independents (56%) are slightly more likely than Democrats (50%) and Republicans (53%) to say they never existed in their community. In the South, however, Democrats (41%) are more likely than Republicans (35%) to say Confederate monuments are present now.

More than one-third of Black Americans (36%)—compared with fewer Hispanic Americans (24%), multiracial Americans (22%), AAPI (19%), and white Americans (19%)—say that there are currently Confederate monuments in their community. White Southerners (38%) are more likely than all white Americans to say there are currently local monuments, but they are still less likely than Black Southerners (43%) to say this is true.

Public Places Named for Confederate Leaders

More than one in five Americans (22%) say that they are aware of buildings, parks, schools, or streets that commemorate Confederate leaders in their community right now, while 22% say such memorials used to exist but don’t anymore, and 51% of say there have never been these types of public display in their community. In the South, 36% say these commemorations currently exist and only 28% say they never existed, compared to 15% who say they exist now and 63% who say they never existed in the rest of the country.

There are only small partisan differences in awareness of places named for Confederate leaders in local communities right now, as 24% of Democrats, 23% of independents, and 20% of Republicans report they currently exist. Democrats (23%) and Republicans (25%) are more likely than independents (19%) to say these places existed but don’t anymore, and independents (55%) are slightly more likely than Democrats (49%) and Republicans (52%) to say they never existed in their community. Again, in the South, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say these places exist currently (40% vs. 31%).

Black Americans are the most likely to report that there are currently public spaces named for Confederate leaders (35%), compared with fewer multiracial Americans (27%), Hispanic Americans (25%), white Americans (19%), and AAPI (18%). White Americans in the South are more likely than in the rest of the country to report these places existing now (36%), while Black Southerners are even more likely to say so (42%).

Awareness of Discriminatory and Racist Practices

Public School Segregation

Less than one in ten Americans (7%) say there are currently laws or practices that segregate public schools by race in their community. More than four in ten say there were such laws in the past (43%), and almost half of Americans (47%) say that there have never been laws or practices that segregated public schools in their community. In the South, 9% say these laws or practices exist currently, 52% say they existed in the past, and 36% say they never existed.

Democrats (11%) are more likely than independents (7%) and Republicans (2%) to say they are aware of current laws or practices that segregate public schools by race in their community. Democrats (49%) are also more likely than independents (40%) and Republicans (40%) to say these laws or practices existed in the past but no longer do. Conversely, Republicans (56%) and independents (50%) are more likely than Democrats (38%) to say these laws or practices never existed in their community. Democrats in the South are more likely than Republicans in the South to say these laws or practices exist now (12% vs. 2%) or did in the past (57% vs. 52%).

Black Americans (23%) are more than twice as likely as AAPI (11%), Hispanic (6%), or white Americans (4%) to say that there are currently practices in place in their community that segregate public schools by race. There are not significant differences between responses in the South and nationally.

Housing Segregation

Seven percent of Americans say that there are currently laws or practices in their community that prevent nonwhite people from living in areas of the city designed for whites, while 39% say that they were aware of such practices in the past, and half of Americans say they have never heard of that happening in their community (50%). While similar numbers of people in the South (8%) and in the rest of the country (7%) say these laws or practices exist now, more residents of the South (47%) say they used to exist than those living elsewhere (35%).

Again, Democrats (13%) are more likely than independents (6%) and Republicans (3%) to say they are aware of current laws or practices that segregate housing by race in their community. Democrats (46%) are also more likely than independents (40%) and Republicans (32%) to say these laws or practices existed in the past but no longer do. Conversely, Republicans (63%) and independents (52%) are more likely than Democrats (38%) to say these laws or practices never existed in their community. These same patterns hold true in the South.

Almost a quarter of Black Americans (24%) say there are currently laws or practices that prevent nonwhite people from living in certain areas of the city where they reside, compared with 9% of Hispanic Americans and 4% of white Americans who say the same. Responses in the South are not different from those nationally.

Support for Preserving the Legacy of the Confederacy

Americans are divided over whether they support or oppose efforts to preserve the legacy and history of the Confederacy through public memorials and statues in their community. A slim majority support preserving Confederate history using memorials and statues (51%), while 46% are opposed. Republicans overwhelmingly back efforts to preserve the legacy of the Confederacy (85%), compared with less than half of independents (46%) and only one in four Democrats (26%). The contrast between white Republicans and white Democrats is stark.

Nearly nine in 10 white Republicans (87%), compared with 23% of white Democrats, support efforts to preserve the legacy of the Confederacy.

Just a quarter of Black Americans (23%), compared with majorities of white Americans (57%) and Hispanic Americans (55%), express support for preserving the history of the Confederacy with memorials and statues.[3]

Among religious groups, white evangelical Protestants are the most likely to support preserving the history of the Confederacy with memorials and statues (76%). Majorities of white mainline Protestants (65%), Latter-day Saints (65%), Hispanic Catholics (63%), white Catholics (60%), and Hispanic Protestants (58%) do as well, along with just under half of other Protestants of color (49%). Around one-third of other non-Christian religious Americans (35%), Jewish Americans (34%), other Christians (33%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (33%) support Confederate preservation. Black protestants are the least likely to support these memorials (29%).

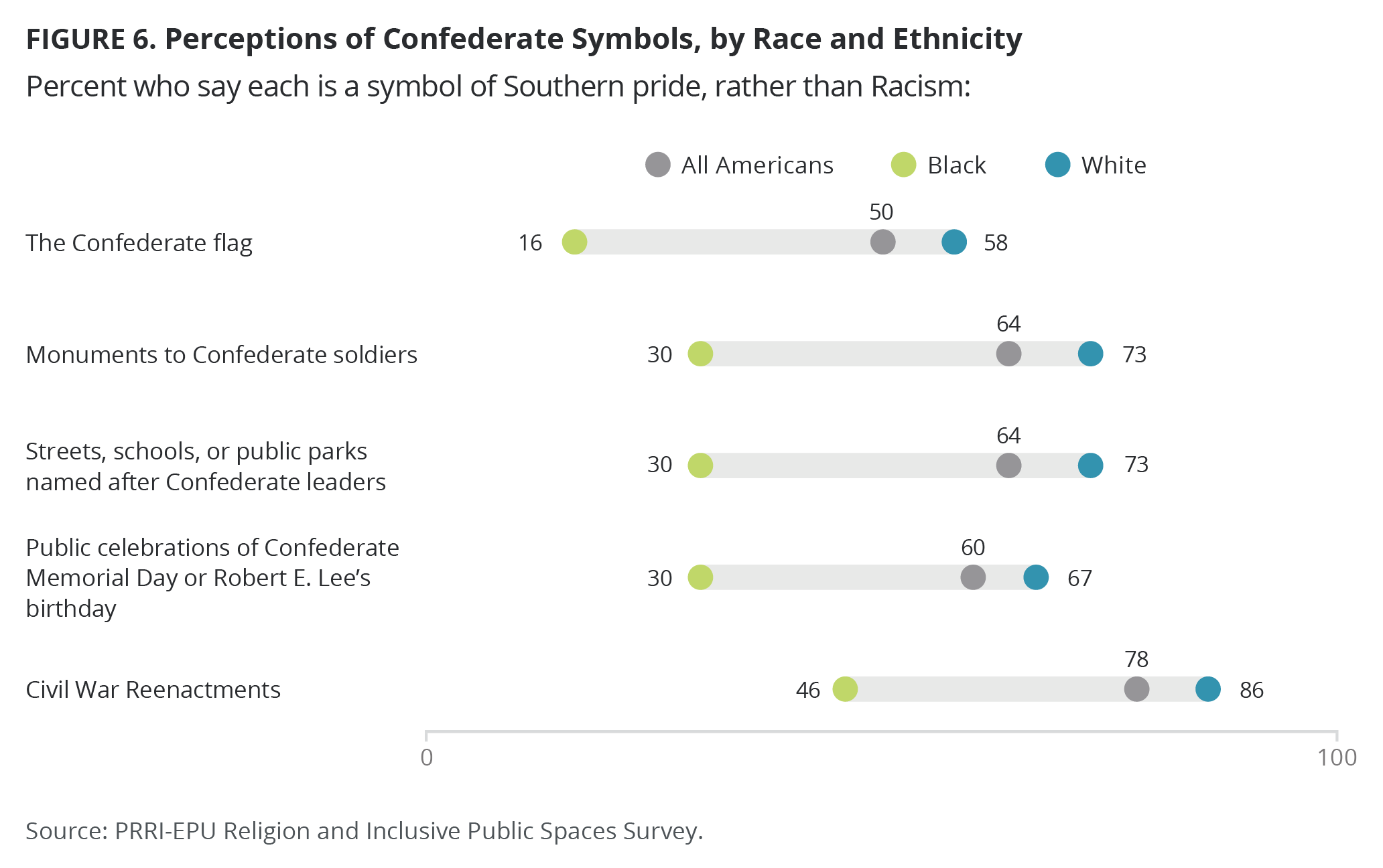

Americans are also divided in their interpretations of the Confederate flag: 50% see it primarily as a symbol of Southern pride, while 47% see it mostly as a symbol of racism. This even division has remained relatively steady since PRRI began tracking this question, in 2015. More than eight in ten Republicans (83%) say it is a symbol of Southern pride, compared with less than half of independents (48%) and one in four Democrats (25%).

A majority of white Americans (58%), compared with less than half of Hispanic Americans (48%), multiracial Americans (43%), and AAPI (35%), and just 16% of Black Americans, say the flag is primarily a symbol of Southern pride.

Americans are less divided over the public presence of other Confederate symbols, however. Around six in ten Americans see monuments to Confederate soldiers (64%); streets, schools, or public parks named for Confederate leaders (64%); and public celebrations of Confederate Memorial Day or Robert E. Lee’s Birthday (60%) as expressions of Southern pride rather than as expressions of racism.

Nine in ten Republicans see each of these as a symbol of Southern pride: 92% say that about monuments to Confederate soldiers, 92% about areas named after Confederate leaders, and 90% about public celebrations of Confederate Memorial Day or Robert E. Lee’s birthday. Majorities of independents also say each of these is an expression of Southern pride (65%, 65%, and 58%, respectively). By contrast, only about four in ten Democrats (42%, 43%, and 39%, respectively) see these public recognitions of the Confederacy as expressions of Southern pride.

Across all three of these Confederate symbols, the perspectives of African Americans strongly diverge from those of white Americans. More than six in ten Black Americans consider them symbols of racism: 63% say that regarding streets, schools, and parks named for Confederate leaders, 63% regarding monuments to Confederate soldiers, and 63% regarding public celebrations of Confederate Memorial Day or Robert E. Lee’s birthday. Half or more of Americans of other races or ethnicities say that each of these is a symbol of southern pride.

Nearly eight in ten Americans (78%) view Civil War reenactments as an expression of Southern pride, versus 18% who say they are symbols of racism. More than nine in ten Republicans (94%), nearly eight in ten independents (79%), and more than six in ten Democrats (64%) say reenactments are an expression of Southern pride. Black Americans are divided, with 46% finding reenactments racist and 46% seeing them as an expression of Southern pride. The views of Hispanic Americans (70%) are closer to those of white Americans (86%), with a strong majority seeing Civil War reenactments as expressions of Southern pride.

Confederacy vs. Diversity in Public Spaces

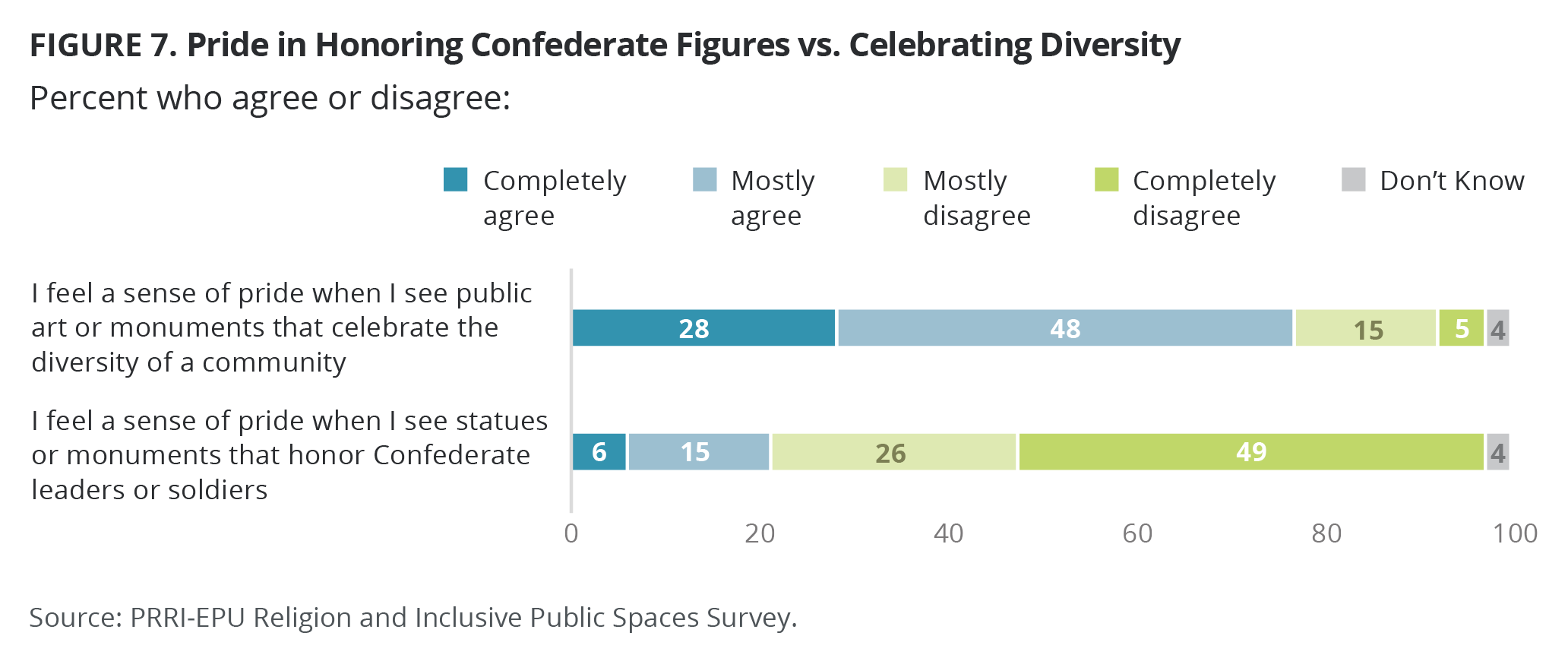

Around one in five Americans (21%) agree with the statement “I feel a special sense of pride when I see statues or monuments that honor Confederate leaders or soldiers,” while three in four disagree (75%), including half who completely disagree (49%). In comparison, 76% of Americans agree with the statement “I feel a special sense of pride when I see public art or monuments that celebrate the diversity of a community,” while 20% disagree.

Republicans (38%) are particularly likely to say that Confederate monuments make them feel proud, compared with significantly fewer independents (16%) and Democrats (14%). Democrats (88%) are more likely than independents (79%) or Republicans (65%) to say they feel pride when they see public art or monuments that celebrate diversity.

Interestingly, AAPI (29%), Hispanic Americans (22%), and white Americans (21%) are similarly likely to agree that Confederate monuments spark a sense of pride, compared with about half as many Black Americans (12%). Majorities of Hispanic Americans (80%), white Americans (76%), and Black Americans (75%) agree that public art or monuments that celebrate diversity make them feel a sense of pride.

Less than one in ten Americans (6%) say that they have volunteered or given money to groups that protect or preserve Confederate monuments in the past year, while 92% say they have not done so. Americans are much more likely to report that they have volunteered or given money to groups supporting racial equality (34%), while 63% have not. Around half of Black Americans (49%), compared with around one-third of Hispanic Americans (33%), AAPI (32%), and white Americans (32%) say they have volunteered or given money to groups supporting racial equality.

Six percent of Americans say that they have flown or displayed a Confederate flag in the past year, while 91% say they have not. Comparatively, a majority of Americans (55%) have flown or displayed an American flag over the past year. Slightly more Democrats (95%) and independents (94%) than Republicans (89%) say they have never flown a Confederate flag. A majority of Democrats (58%), compared with 43% of independents and 21% of Republicans, say they have not flown the American flag in the last year. White Americans (65%) are more likely than Hispanic Americans (42%) and Black Americans (32%) to report that they have displayed or flown an American flag.

Confederate Memorials and Consensus for Change

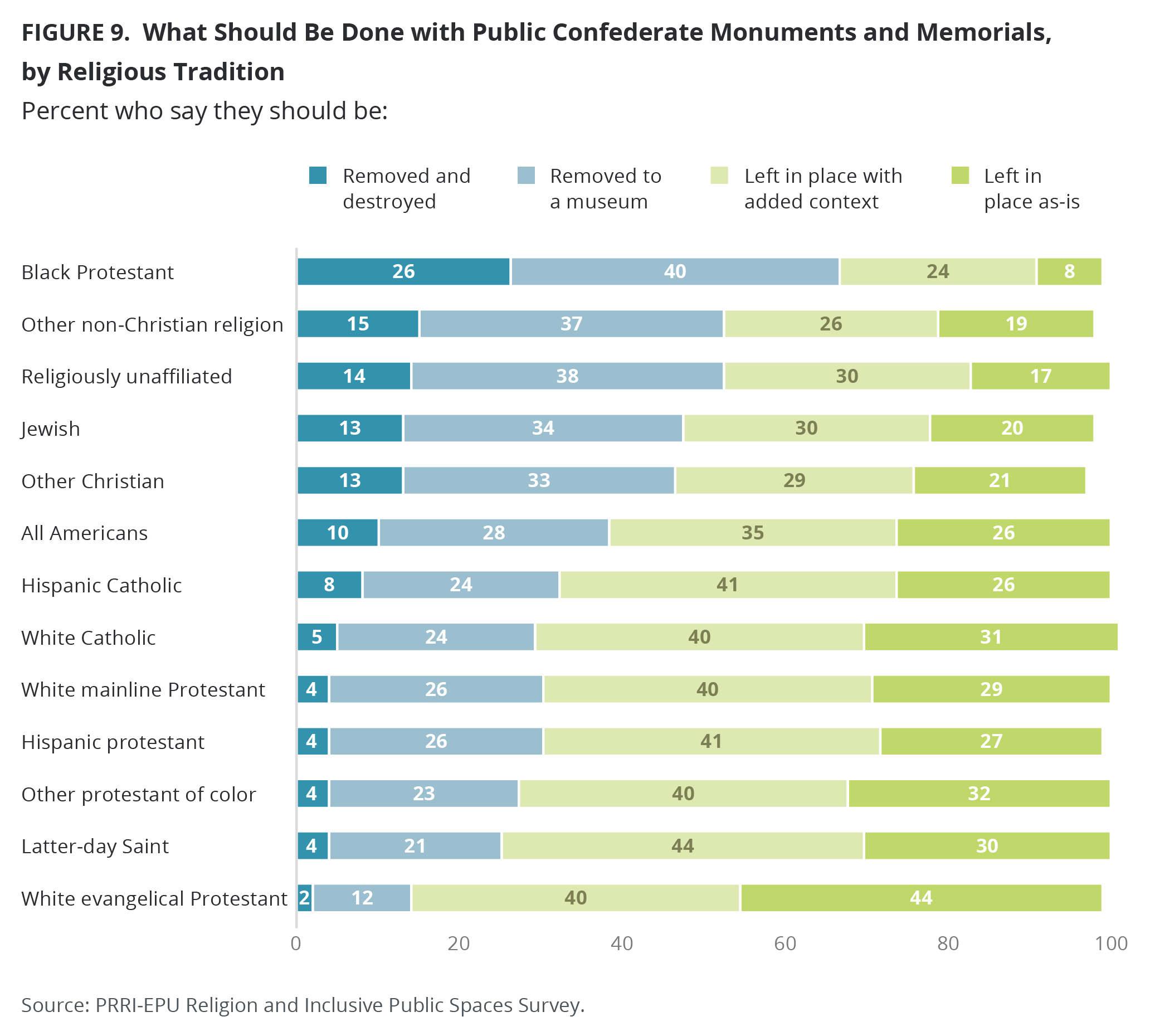

What Should Be Done with Confederate Memorials?

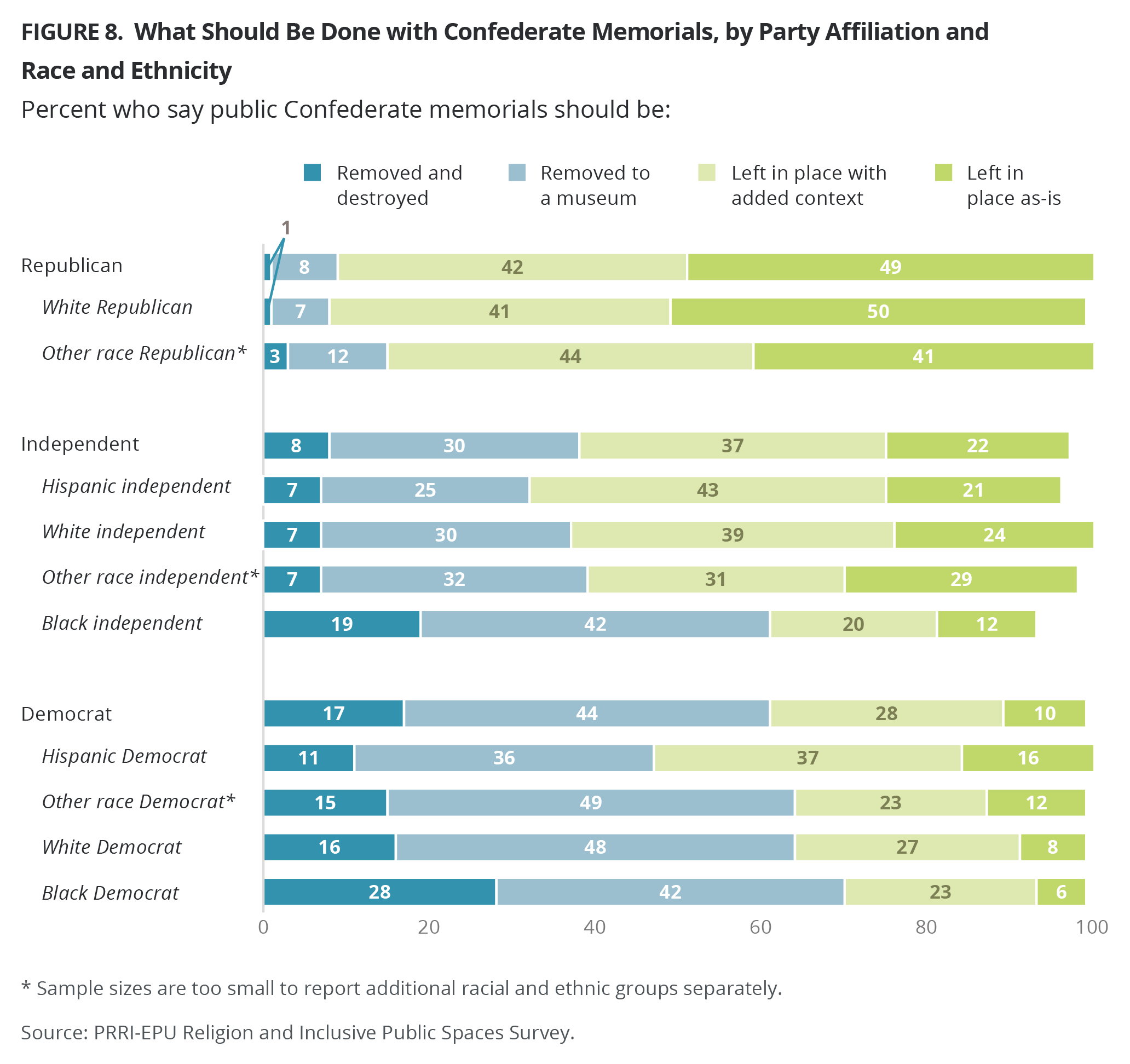

Americans are divided over what to do with Confederate memorials and monuments. Around a quarter of Americans say they should be left in place as they are (26%), one-third say they should be left in place with added information about the history of slavery and racism (35%), 28% say they should be removed and put in a museum, and 10% say they should be removed and destroyed.

Republicans are the least supportive of taking action on Confederate monuments and memorials. Just 1% of Republicans say monuments should be removed and destroyed, compared with 8% of independents and 17% of Democrats. A plurality of Democrats (44%) support moving monuments to museums, compared to 30% of independents and just 8% of Republicans. Roughly four in ten Republicans (42%) and independents (37%) support adding context to monuments, along with 28% of Democrats. Half of Republicans (49%) support leaving monuments as they are, compared with 22% of independents and 10% of Democrats.

Black Democrats (28%) are more likely to support removing and destroying Confederate monuments than white Democrats (16%) or Hispanic Democrats (11%). Just less than half of white Democrats (48%), compared with 42% of Black Democrats and 36% of Hispanic Democrats, support moving monuments to museums. The same race trends hold among independent Americans. One in five Black independents support removing and destroying monuments (19%), and four in ten support moving them to a museum (42%), compared with fewer white independents (7% and 30%, respectively), Hispanic Americans (7% and 25%), and independents of other races and ethnicities (7% and 32%). There are no significant differences by race among Republicans.

Black Americans are the most supportive of removing Confederate memorials: 25% say they should be removed and destroyed, and an additional 39% say they should be placed in a museum. Meanwhile, 23% say they should remain in place with added context, and less than one in ten (9%) say they should remain in place as they are. By contrast, only a third of white Americans say that memorials should be removed, with 7 % saying they should be destroyed and 26% saying they should be placed in museums. Nearly seven in ten white Americans say either that monuments should remain in place with added context (37%) or that they should remain in place as they are (30%).

White Americans are divided along educational lines in their attitudes toward monuments. White Americans with at least a four-year college degree are about twice as likely as those without a degree to say monuments should be removed and destroyed (11% vs. 5%) or removed and placed in a museum (36% vs. 19%). Whites without four-year degrees are slightly more likely than those with four-year degrees to support leaving monuments in place with added context (39% vs. 33%) or leaving them in place as they are (36% vs. 20%).

Non-Black Christian groups are the least likely to support removing monuments. Just 2% of white evangelical Protestants say statues should be removed and destroyed, along with 4% of white mainline Protestants, 4% of Hispanic Protestants, 4% of other Protestants of color, 5% of white Catholics, and 8% of Hispanic Catholics. More than one in ten other Christians (13%), Jewish Americans (13%), other non-Christian religious Americans (15%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (14%) favor destroying Confederate monuments. Black Protestants are the religious group most likely to want Confederate monuments removed and destroyed (26%).

Again, with the exception of Black Protestants, among most Christian groups, roughly a quarter of most Christian groups favor moving Confederate monuments to museums. This includes 23% of other Protestants of color, 24% of white Catholics, 24% of Hispanic Catholics, 26% of Hispanic Protestants, and 26% of white mainline Protestants. Only 12 % of white evangelical Protestants support moving the monuments to museums. More than one-third of other Christians (33%), Jewish Americans (34%), other non-Christian religious Americans (37%), or religiously unaffiliated Americans (38%) say monuments should be moved to museums. Again, Black Protestants stand out with 40% saying monuments should be relocated.

Just one-quarter of Black Protestants (24%) say monuments should remain in place with added context, compared with four in ten members of other Christian denominations, including 40% of white evangelical Protestants, 40% of white mainline Protestants, 40% of other Protestants of color, 40% of white Catholics, 41% of Hispanic Catholics, and 41% of Hispanic Protestants. Around three in ten Jewish Americans (30%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (30%), other Christians (29%), and other non-Christian religious Americans (26%) say monuments should remain in place with added context.

Finally, just 8% of Black Protestants support leaving monuments in place as they are now, compared with a plurality of white evangelical Protestants (44%), 32% of other Protestants of color, 31% of white Catholics, 29% of white mainline Protestants, 27% of Hispanic Protestants, and 26% of Hispanic Catholics. Around one in five other Christians (21%), Jewish Americans (20%), other non-Christian religious Americans (19%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (17%) favor leaving monuments as they are now.

A Typology of Attitudes Toward Monument Reform

To better understand Americans’ attitudes toward removing Confederate symbols and reimagining public spaces, PRRI created a four-point “monument reform” scale. See appendix A for the methodology used to create the scale.

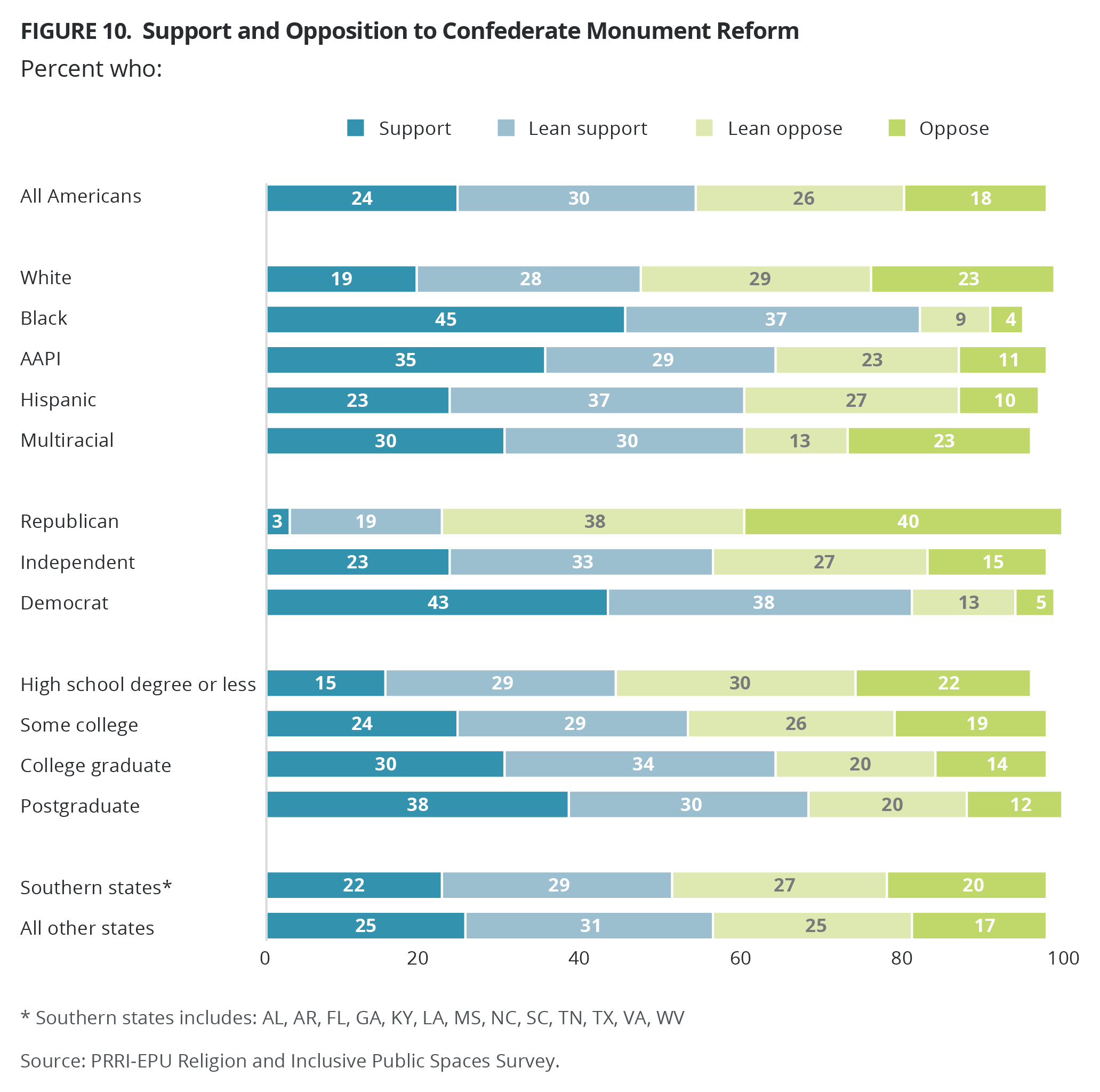

Around one in four Americans (24%) are full supporters of monument reform. This group sees Confederate monuments and the Confederate flag as expressions of racism and strongly supports reforming public spaces and removing Confederate symbols and names. On the opposite end of the scale, just under one in five Americans (18%) are full opponents of monument reform. This group sees Confederate monuments and the Confederate flag as expressions of Southern pride and supports keeping monuments in place as they are. Three in ten Americans (30%) have mixed views but generally lean toward reform. Around one in four Americans (26%) have mixed views on Confederate monuments but lean against reform.

These distributions do not vary by region — Americans living in the South are similarly situated as all Americans.

Support for Monument Reform

A majority of Americans (54%) support monument reform, including roughly one in four (24%) who are fully supportive of monument reform and another 30% who lean toward supporting monument reform. Full supporters see Confederate symbols as expressions of racism and nearly universally support reimagining public spaces with an eye to their community’s diversity. Americans in the South are as likely to fully support monument reform (22%) as Americans nationally. Those who lean toward supporting reform believe that Confederate figures should not be memorialized and feel that context should be added to existing memorials.

More than four in ten Democrats (43%) fully support monument reform, along with an additional 38% who lean toward support. In comparison, fewer independents fully support reform (23%), while a plurality (33%) lean toward supporting reform. Just 3% of Republicans fully support reform, and an additional 19% lean toward reform. White partisan groups express minimal differences when compared with the partisan groups as a whole.

More than four in ten Black Americans fully support monument reform (45%), and 37% lean toward support. A majority of AAPI either fully support (35%) or lean toward support (29%), and the same is true of Hispanic Americans (23% fully support, 37% lean toward support) and multiracial Americans (30% fully support, 30% lean toward support). Just less than half of white Americans either fully support monument reform (19%) or lean toward support (28%).

There are some key divisions along education lines in support for monument reform. White Americans who don’t have a four-year college degree (13% fully support, 25% lean toward support) are much less likely to support monument reform than white Americans with at least a four-year college degree(29% fully support, 32% lean toward support). Black Americans without a four-year college degree (42% fully support, 38% lean toward support) are also less likely than those with at least a four-year degree (54% fully support, 36% lean toward support) to be in favor of monument reform. This pattern is similar among Hispanic Americans (20% of those without a four-year degree fully support, 37% of those with a four-year degree fully support).

Christians of color, non-Christians, and the religiously unaffiliated are some of the most likely to fully support monument reform, including Black Protestants (46% fully support, 41% lean support), religiously unaffiliated Americans (38% fully support, 30% lean support), non-Christian religious Americans (37% fully support, 28% lean support), other Christians (37% fully support, 33% lean support), and Jewish Americans (29% fully support, 34% lean support). By comparison, Hispanic Catholics (18% fully support, 39% lean support), Hispanic Protestants (17% fully support, 43% lean support), white mainline Protestants (15% fully support, 28% lean support), white Catholics (14% fully support, 31% lean support), Latter-day Saints (11% fully support, 33% lean support), and white evangelical Protestants (6% fully support, 22% lean support) are less likely to support monument reform.

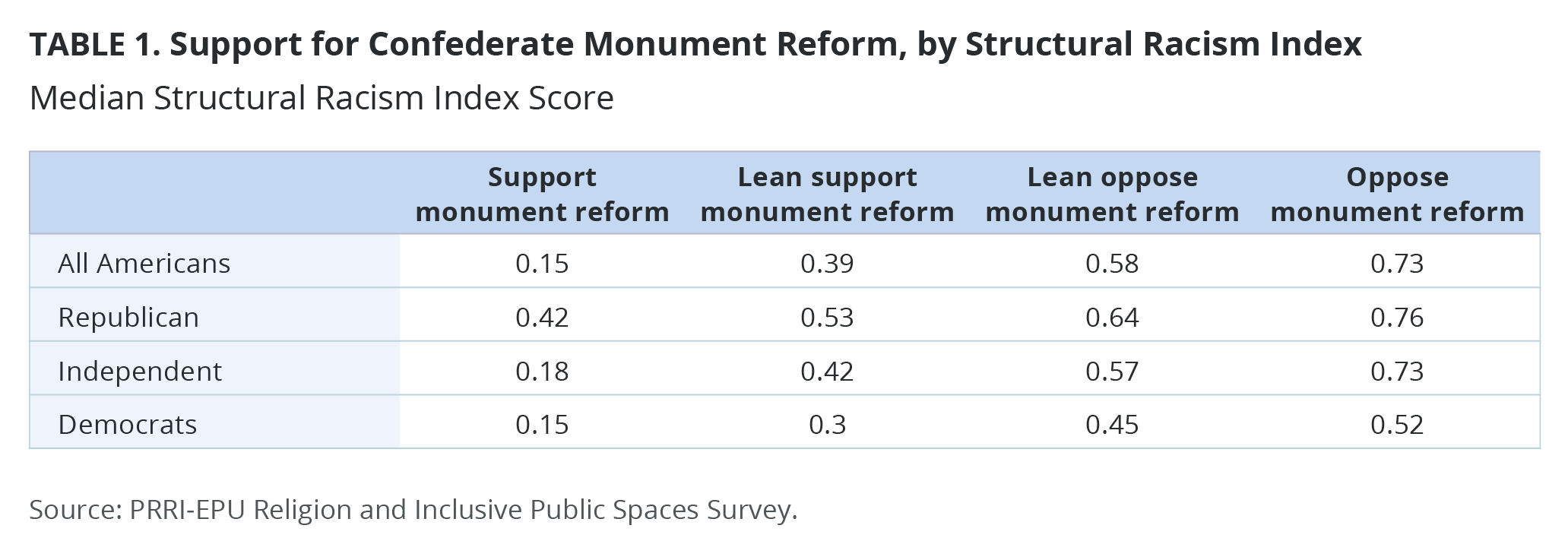

Relationships Between the Structural Racism Index and Support for Monument Reform

Attitudes toward monument reform and structural racism are highly correlated. Americans who fully support monument reform have a median structural racism index score of just 0.15, far below the median score of the general population (0.45). Similarly, Americans who lean toward supporting monument reform have a median structural racism index score of 0.39, while Americans who lean against monument reform have a median score of 0.58, and Americans who oppose monument reform have a median score of 0.73.

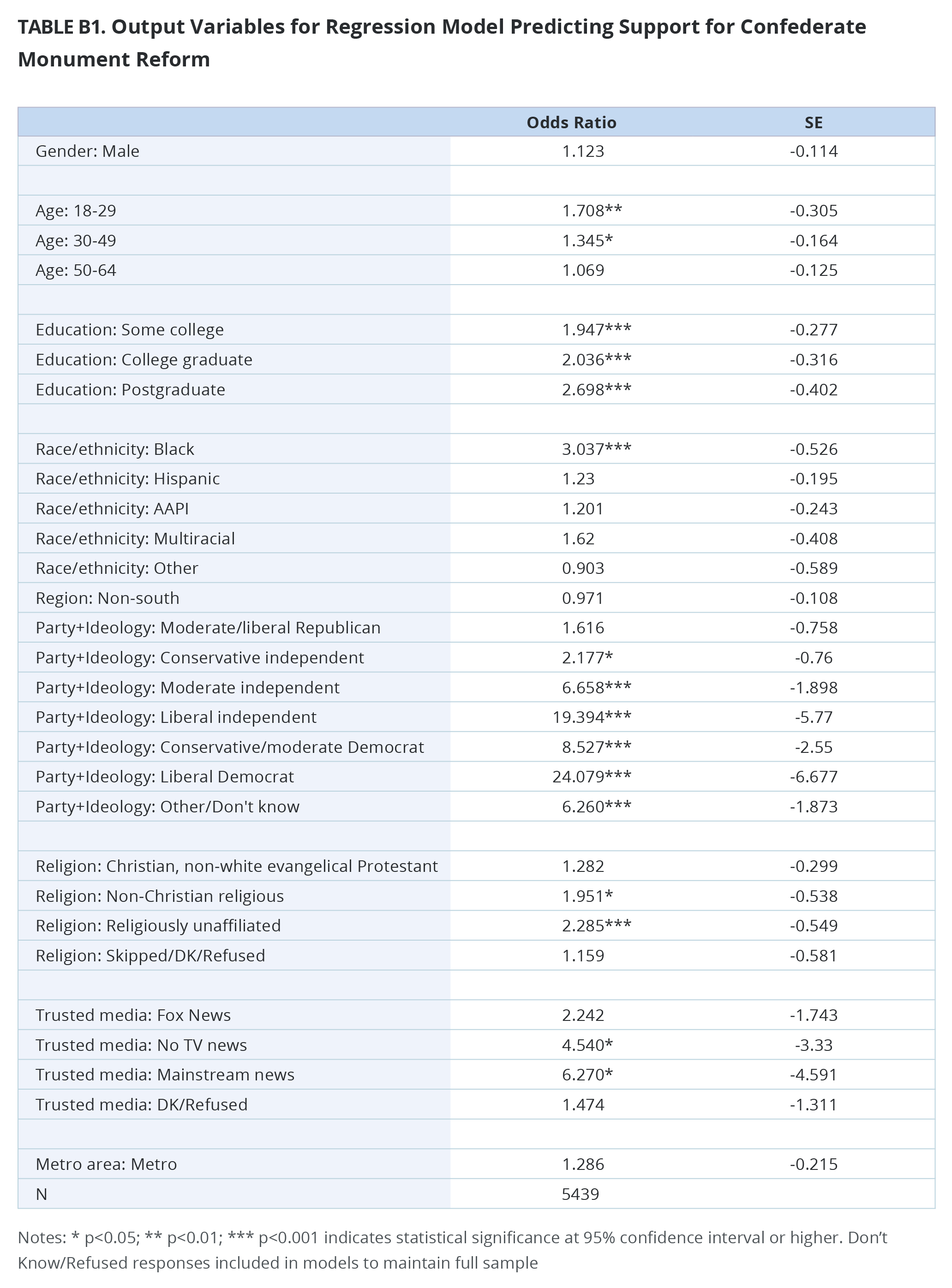

Explaining Support for Monument Reform

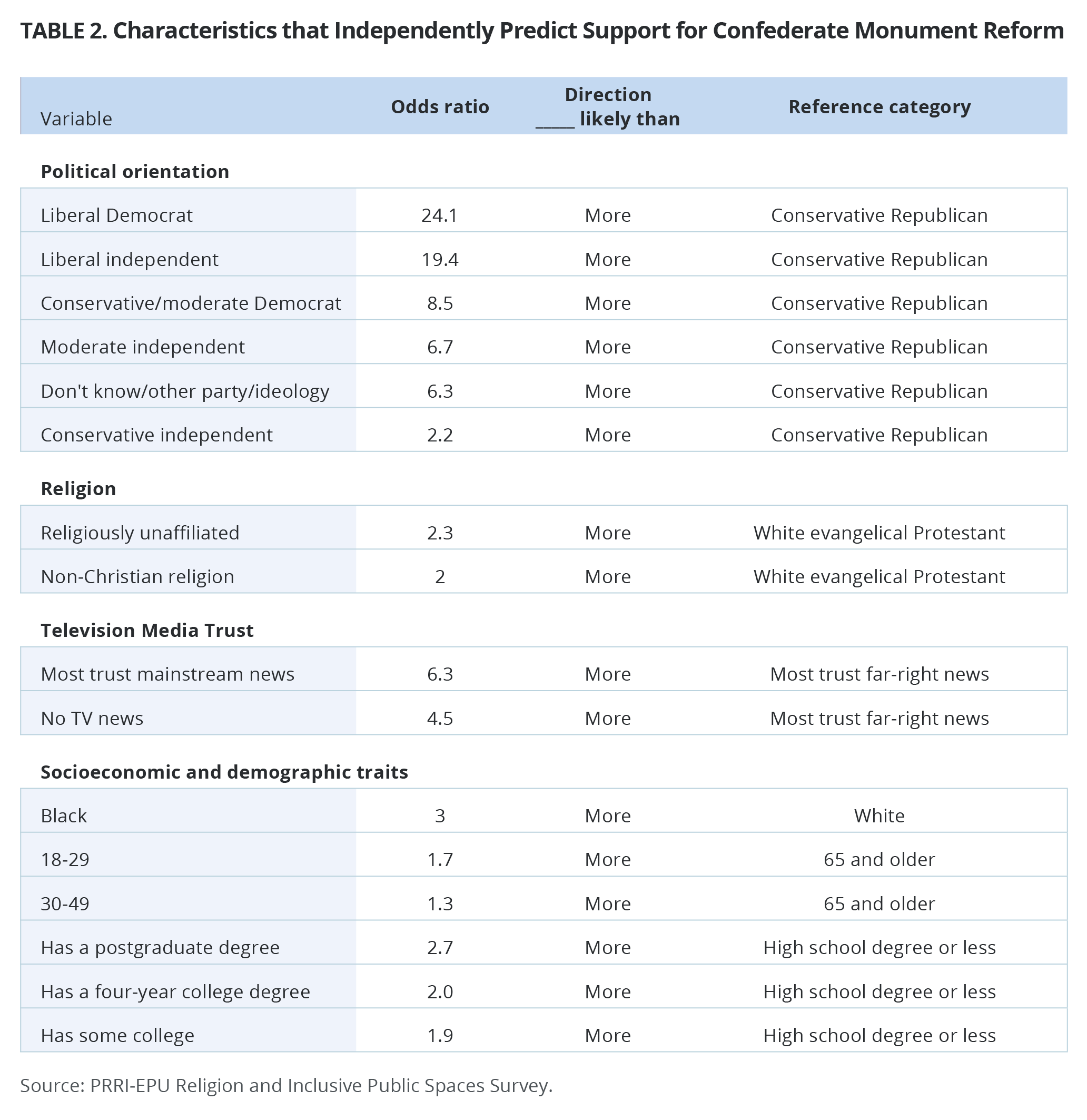

PRRI constructed a logistical regression model to explain which characteristics are most associated with being a full supporter of monument reform.[4]

Partisanship and ideology are the strongest independent predictors of whether someone supports monument reform. Liberal Democrats and liberal independents are more than 20 times more likely than conservative Republicans to fully support monument reform. Conservative and moderate Democrats are more than eight times more likely than conservative Republicans to support monument reform, and moderate independents are more than six times more likely. Even conservative independents are more than twice as likely as conservative Republicans to fully support reform.

Which news sources Americans most trust is also an important factor. Americans who most trust mainstream news outlets are six times more likely to support monument reform than those who most trust far-right news outlets like One America News or Newsmax, while those who do not trust any TV news are more than four times as likely.[5]

To a lesser degree, religious affiliation is also an important factor. Religiously unaffiliated Americans and non-Christian religious Americans are about twice as likely as white evangelical Protestants to fully support monument reform.

Finally, there are some key socioeconomic and demographic traits that help predict full support of monument reform. Black Americans are three times more likely than white Americans to be full supporters, and Americans with at least some education at the college level are about twice as likely as those with a high school degree or less to support monument reform. Finally, younger Americans under the age of 50 are slightly more likely than those over 65 to support reform.

Visions for the Future

Principles for Shaping Public Spaces

Support for Broadly Welcoming Spaces

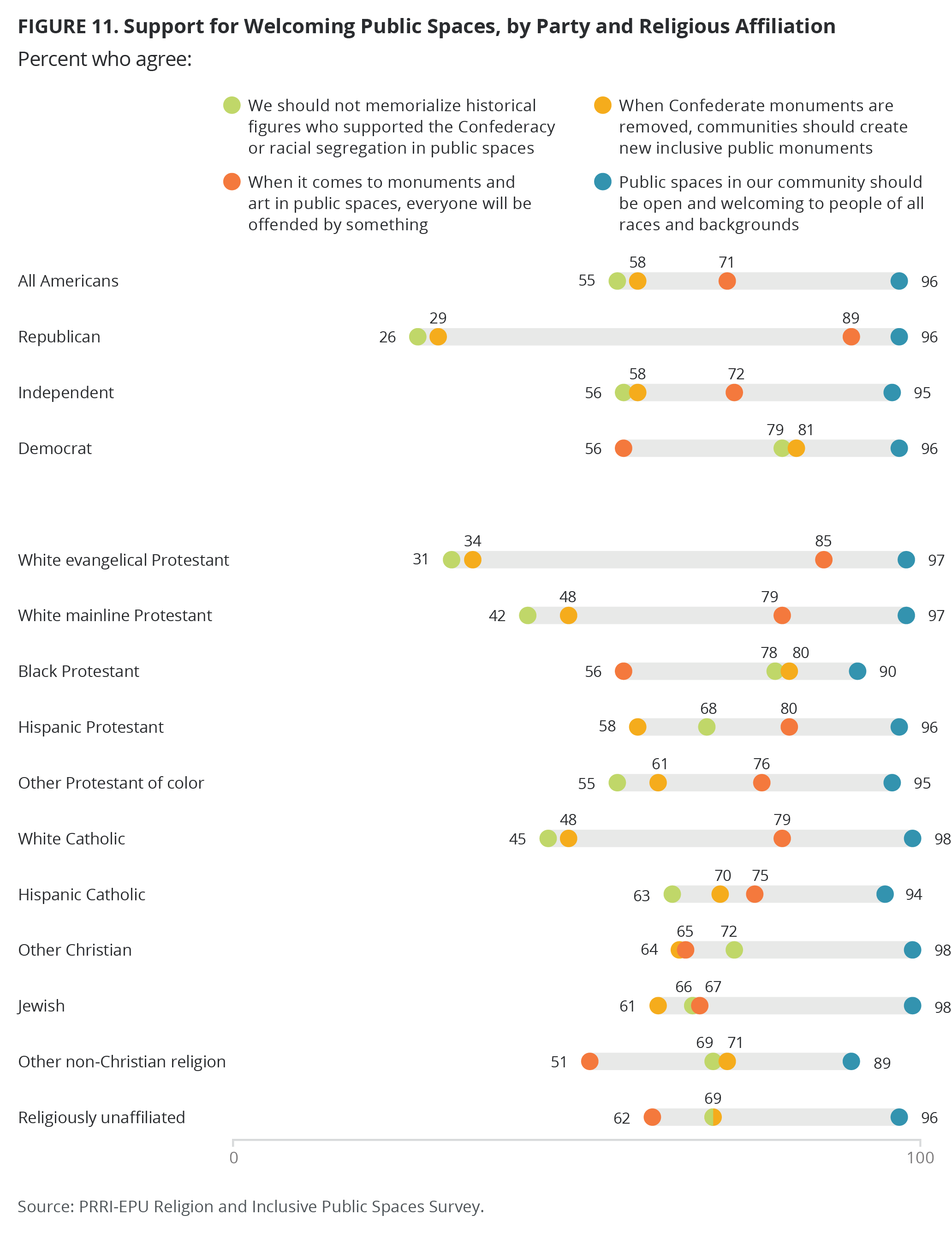

Nearly all Americans (96%) agree with the statement “public spaces in our community like parks, libraries, government buildings, and public university campuses should be open and welcoming to people of all races and backgrounds.” Vast majorities of Americans, across categories of party, religion, race, and education, agree with this statement.

However, views are more mixed when it comes to the current presence of memorials to the Confederacy, what should be done after Confederate monuments are removed, and the possibility of designing public spaces to include everyone.

Creating New Public Monuments

Americans are divided over their responses to the statements “we should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces” (55% agree vs. 42% disagree) and “when Confederate monuments are removed, communities should create new public monuments and art that represent the values of racial equality and inclusivity (58% agree vs. 39% disagree). Democrats (79% and 81%, respectively, agree with the statements) are about three times as likely as Republicans (26% and 29%) to agree with both statements. Independents are in between (56% and 58%).

White Americans are the least likely to agree with both statements (48% and 51%), compared to majorities of multiracial Americans (53% and 55%), two-thirds of Hispanic Americans (67% and 69%), and three in four AAPI (75% and 74%) and Black Americans (76% and 77%).

With the exception of white Christian groups, majorities of members of all religious groups agree with both statements: Black Protestants (78% and 80%), other Christians (72% and 64%), members of other non-Christian religion (69% and 71%), religiously unaffiliated (69% both), Hispanic Protestants (68% and 58%), Jewish (66% and 61%), Hispanic Catholics (63% and 70%), and other Protestants of color (55% and 61%). Less than half of white Catholics (45% and 48%) and white mainline Protestants (42% and 48%) agree with these statements, and only about one third of white evangelical Protestants (31% and 34%) agree with both statements.

Signs of Fatigue and Cynicism: Everyone Will Be Offended by Something

A sizeable majority of Americans (71%) agree with the statement “when it comes to monuments and art in public spaces, everyone will be offended by something; there is no point in trying to please everyone.” This includes 35% who strongly agree, compared with 28% who disagree. Nearly nine in ten Republicans (89%) agree, compared with 56% of Democrats. Independents (72%) resemble Americans overall.

A slim majority of Black Americans (51%) agree that everyone will be offended by something, compared with 62% of multiracial Americans, 67% of AAPI, 73% of Hispanic Americans and 75% of white Americans. There is variation by education, however. Americans without a college degree are more likely than Americans with a college degree to agree with this statement across all race categories: white (80% vs. 66%), Hispanic (75% vs. 62%), and Black Americans (55% vs. 42%).[6]

With the exception of members of non-Christian religions (51%) and Black Protestants (56%), at least six in ten members of other religious groups agree that everyone will be offended by something, including religiously unaffiliated Americans (62%), other Christians (65%), Jewish people (67%), Hispanic Catholics (75%), and Protestants of color (76%). Hispanic Protestants (80%) and white Christians groups—including white evangelical Protestants (85%), white Catholics (79%), and white mainline Protestants (79%)—are the most likely to agree with this statement.

Cynicism about the possibility of creating inclusive public spaces is positively correlated with higher scores on the structural racism index. Those who agree that everyone will be offended by something have a median structural racism index score of 0.52, compared with a median score of 0.22 among those who disagree with that statement.

Changes in the Community

Renaming Public Schools and Mascots

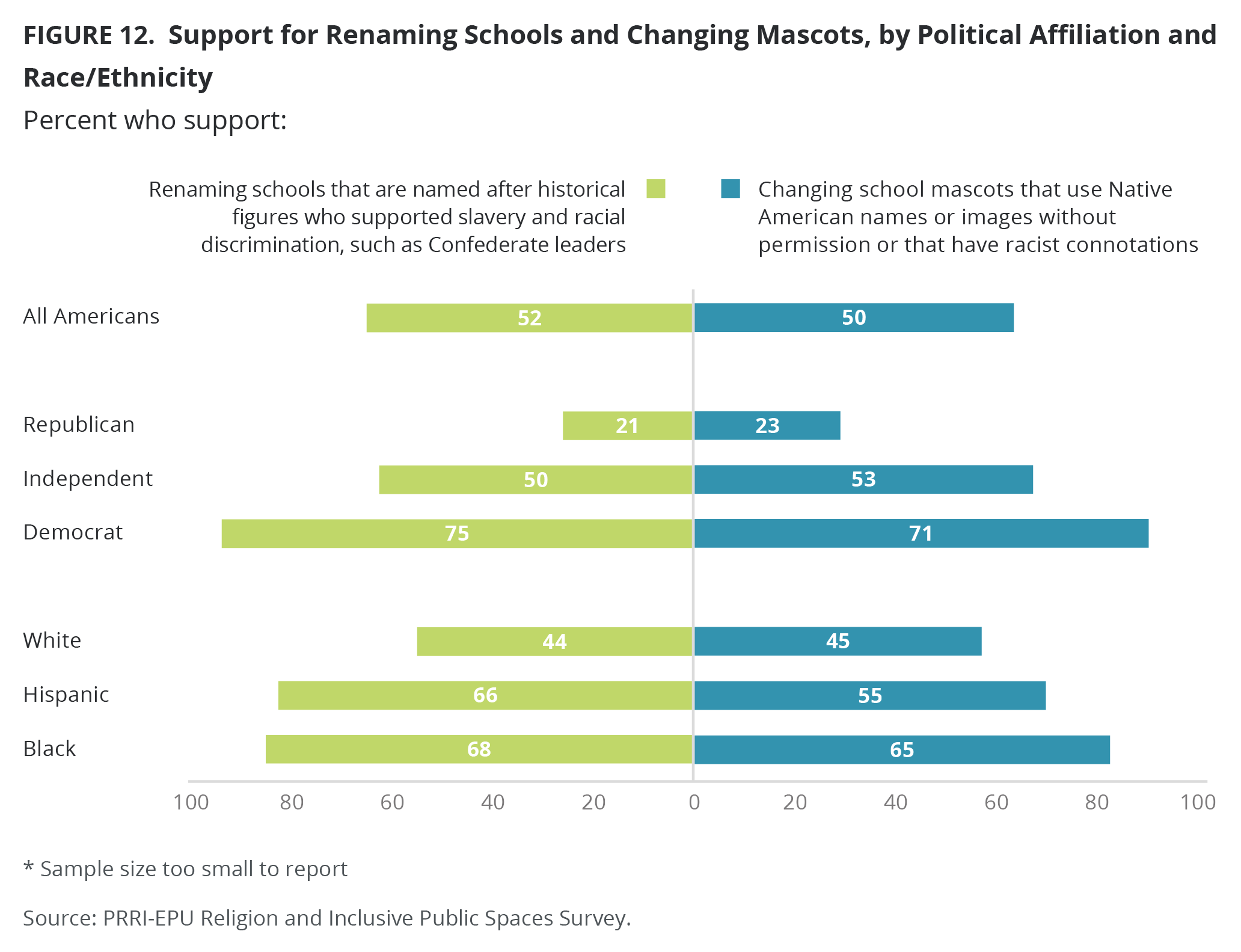

Americans are fairly divided on the question of renaming public schools and mascots that have racist connotations. A slim majority of Americans (52%) favor renaming schools that are named after individuals who supported slavery and racial discrimination, compared with 45% of Americans who oppose such actions. A similar share of Americans (50%) support changing school mascots that use Native American names or images without permission, have racist connotations, or are offensive to certain groups. Less than half (47%) of Americans oppose such measures.

Democrats are the most likely to support renaming schools (75%) and changing mascots that have racist connotations (71%). Around half of independents support each of these initiatives (50% for renaming schools, 53% for changing mascots). Republicans are the least supportive of such measures, with only 21% supporting renaming schools and 23% supporting changing mascots.

Broad majorities of AAPI (71%), Black Americans (68%), and Hispanic Americans (66%) support renaming schools, compared with 44% of white Americans. A slim majority of white Americans (53%) oppose renaming schools. Black Americans (65%) are the most likely to support changing Native American mascots, followed by 55% of Hispanic Americans and 45% of white Americans. However, whites with a college degree are notably more likely than whites without a college degree to support renaming schools (57% vs. 36%) and changing mascots (56% vs. 38%).

Support for renaming schools and changing mascots is not notably lower in the South (50% and 47%) than the whole country.

As age increases, Americans are less likely to support renaming schools or changing school mascots. For ages 18-29, the levels of support for the two propositions are 64% and 58%, respectively; for ages 30-49, support is at 54% for both; among those ages 50-64, it is 49% and. 47%; and for senior Americans 65 and over it is 41% and 43%.

Hispanic Catholics are the most likely to support renaming schools (68%), yet only 46% support changing mascots. Two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated people support renaming schools (66%) and changing mascots (66%). Black Protestants (65% and 67%) and those who follow other non-Christian religions (63% and 66%) show similar levels of support.

Support for changing school names and mascots is lowest among white Christian groups. Around four in ten white mainline Protestants support these measures (43% for renaming, 40% for changing mascots), and support is similar among white Catholics (40% and46%). White evangelical Protestants are the least likely to support renaming schools or changing mascots (22% and 26%).

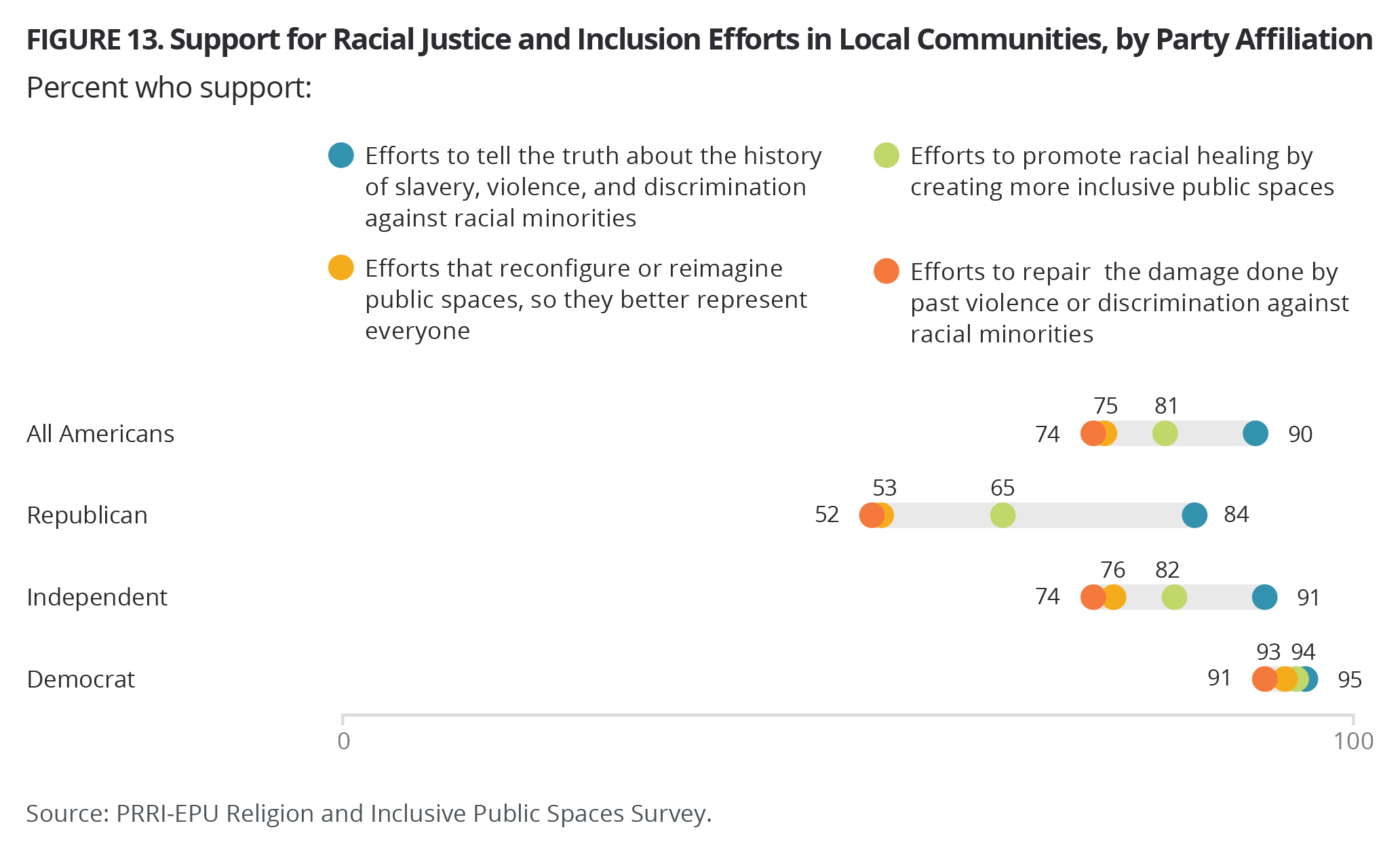

Efforts at Truth-Telling, Racial Healing, Reimagining Public Spaces, and Repairing the Damage from Past Discrimination

Nearly all Americans support “efforts to tell the truth about the history of slavery, violence, and discrimination against racial minorities in your community” (90%) as well as “efforts to promote racial healing by creating more inclusive public spaces in your community” (81%). Additionally, three quarters or more support “efforts that reconfigure or reimagine public spaces so they better represent everyone” (75%) and “efforts to repair the damage done by past violence or discrimination against racial minorities” (74%).

If you exclude Americans who hold the highest scores on the structural racism index, majorities of all other Americans support all four of these efforts. But among Americans who score 0.75 or above on the structural racism index, the only initiative that garners majority support is efforts to tell the truth about the history of slavery, violence, and discrimination against racial minorities (70%). Less than half support the other three efforts: efforts to promote racial healing by creating more inclusive public spaces (42%); efforts that reconfigure or reimagine public spaces (33%); and efforts to repair the damage done by past violence or discrimination against racial minorities (31%).

Nearly all Democrats support with all four propositions (95%, 94%, 93%, and 91%, respectively), compared with fewer Republicans, who are more likely to support efforts to tell the truth about the history of slavery, violence, and discrimination against racial minorities (84%) and efforts to promote racial healing by creating more inclusive public spaces (65%) than to support efforts that reconfigure or reimagine public space (53%) or “efforts to repair the damage done (52%). Independents closely resemble all Americans (91%, 82%, 76% and 74%, respectively).

Vast majorities of all religious groups support efforts to tell the truth about the history of slavery, violence, and discrimination against racial minorities and efforts to promote racial healing. However, among religious groups, support for efforts that reconfigure or reimagine public spaces and efforts to repair the damage done by past violence or discrimination against racial minorities tends to be lower in white Christian groups: white evangelical Protestants (54% and 59%), white Catholics (69% and 67%), white mainline Protestants (71% and 68%), religiously unaffiliated (82% and 79%), members of other non-Christian religions (87% and 80%), Hispanic Catholics (89% and 86%), and Black Protestants (91% and 93%). More than three in four Hispanic Protestants (77%), other Christians (77%), other Protestants of Color (76%) and 70% of Jewish Americans support efforts to repair the damage done by past violence or discrimination against racial minorities.[7]

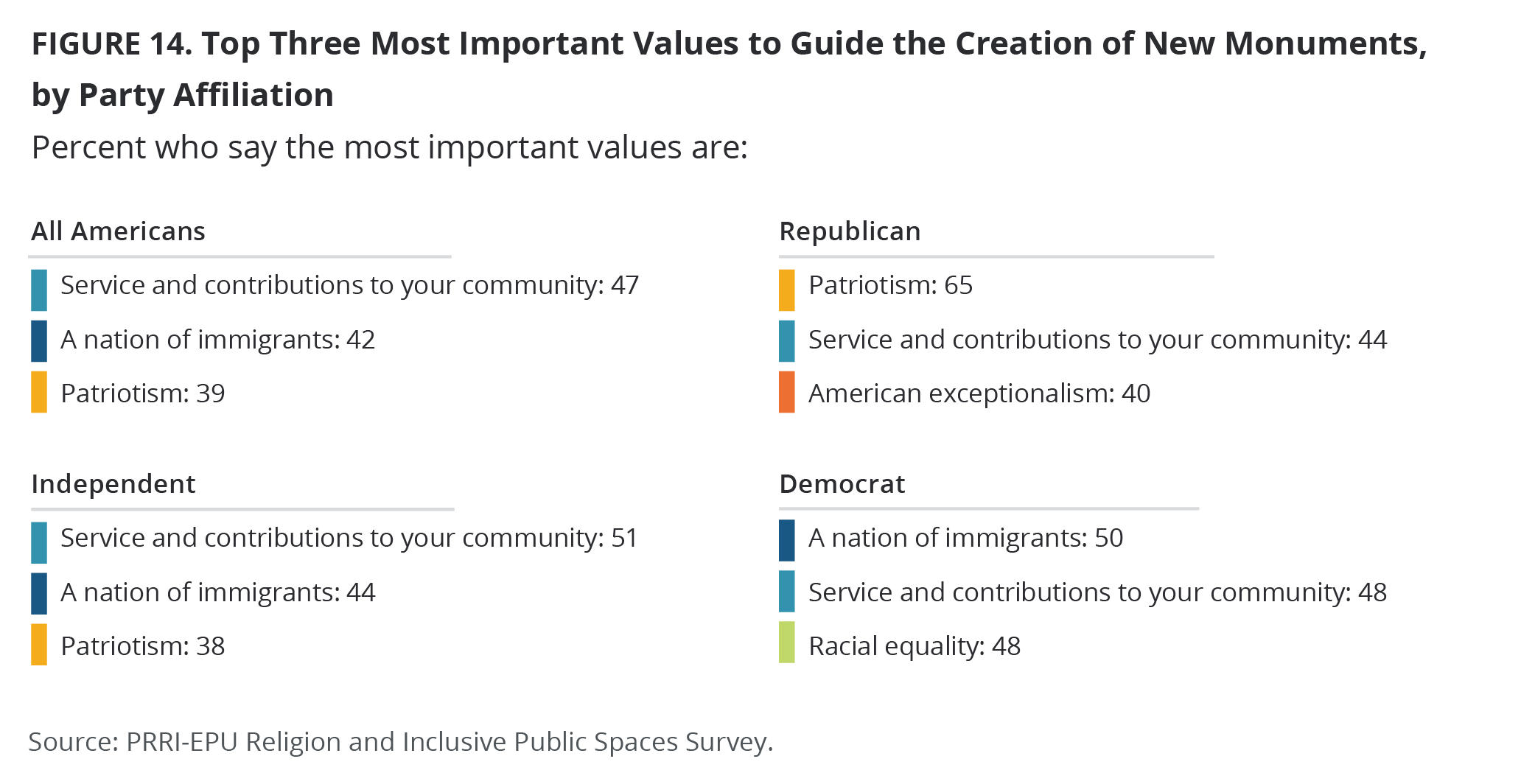

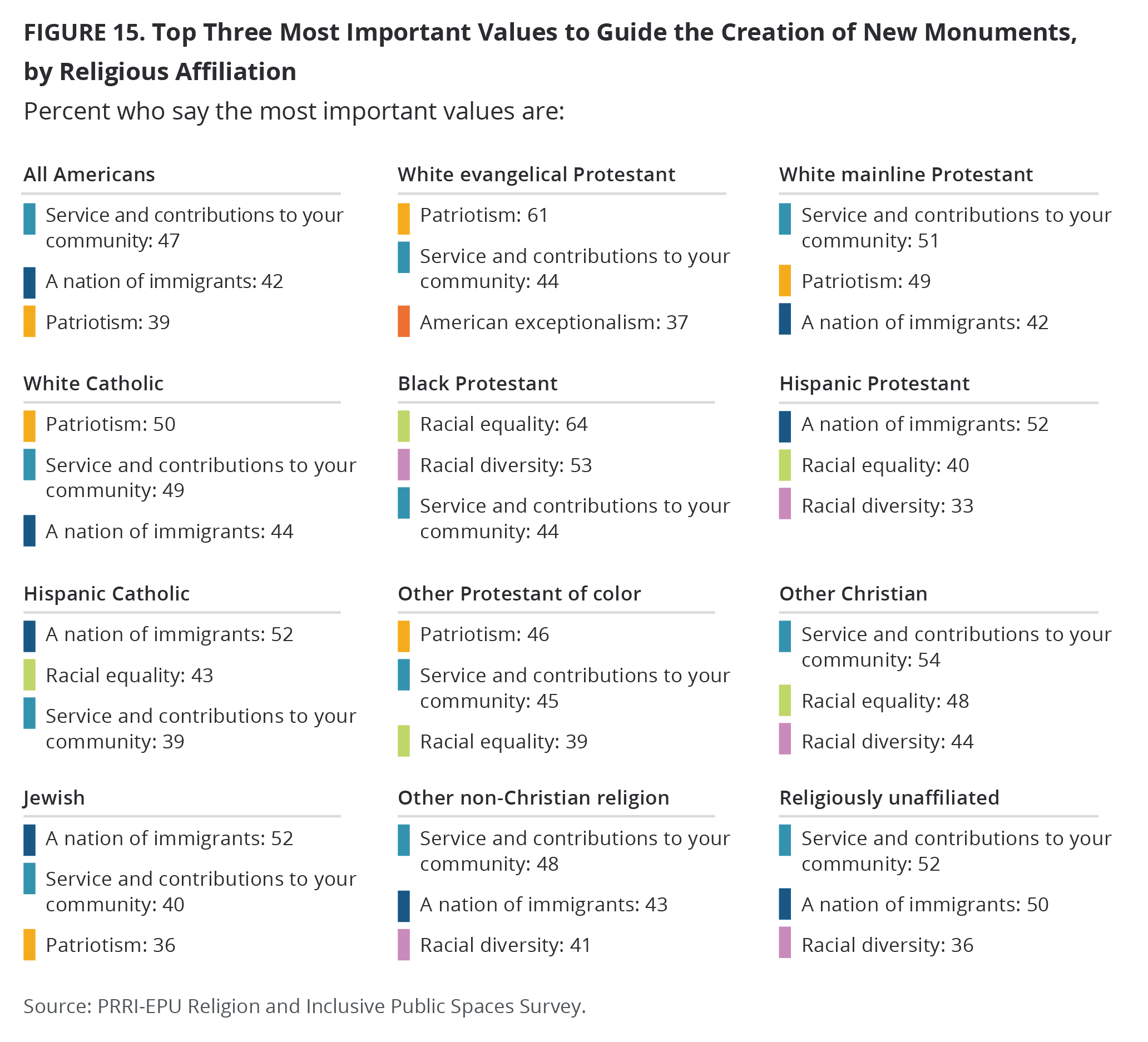

Priorities For New Monuments

We asked Americans to select three values, out of a list of 12, that they believe would be the most important in guiding the creation of new monuments and art in public spaces. The values garnering the most support were service and contributions to the community (47%), the idea of a nation of immigrants (42%), and patriotism (39%). Around three in ten Americans selected racial equality (33%), racial diversity (29%), and American exceptionalism (28%) among their three most important values, compared with smaller proportions who selected religious diversity (14%), gender diversity (12%), Judeo-Christian heritage (4%) or European heritage and civilization (3%).

Interestingly, 21% of Americans selected the American story beginning in 1776 as a top value, compared with 16% of Americans who selected the American story beginning in 1619.

Priorities for New Monuments by Party Affiliation

The values considered most important for the creation of new monuments and art in public spaces vary considerably by partisan affiliation. In fact, there is little overlap in what partisans consider the most important values. The value of service and contributions to the community is the only value that is among the top three for Republicans (44%), Democrats (48%), and independents (51%).

Among Republicans, 65% say that patriotism is among their top values, and 40% selected American exceptionalism. In addition, more than one-third of Republicans (36%) say the American story beginning in 1776 is one of their top three values. By contrast, about half of Democrats rate a nation of immigrants (50%) and racial equality (48%) among their top three values. In addition, 44% of Democrats say racial diversity is a top value. Among independents, 44% chose nation of immigrants and 38% chose patriotism as top three values.

Priorities for New Monuments by Religious Affiliation

The values rated highest by white Christian groups in thinking about the creation of new monuments and art in public spaces are very different from those selected by Christians of color, non-Christian religious Americans, and religiously unaffiliated Americans. The values most often placed in the top three for white evangelical Protestants are patriotism (61%), service and contributions to their communities (44%), and American exceptionalism (37%). About half of white mainline Protestants say service and contributions to their communities (51%), patriotism (49%) and a nation of immigrants (42%) are in the top three most important values. About half of white Catholics say patriotism (50%), service and contributions to their communities (49%), and a nation of immigrants (44%) are among the top three values.

Black Protestants are more likely to select racial equality (64%), racial diversity (53%), and service and contributions to their communities (44%) among their top three most important values. A slim majority of Hispanic Protestants and Hispanic Catholics select a nation of immigrants (52% each) as in their top values, with racial equality (40% and 43%, respectively), and racial diversity (33% and 37%, respectively) also among their top three values.

About four in ten other Protestants of color select patriotism (46%), service and contributions to their communities (45%), and racial equality (39%) among their top three values. The top three values among other Christians are service and contributions to their communities (54%), racial equality (48%), and racial diversity (44%).

The top three values for Jewish Americans are a nation of immigrants (52%), service and contributions to their communities (40%), and patriotism (36%). Finally, members of other non-Christian religions and the religiously unaffiliated rate service and contributions to their communities (48% and 52%), a nation of immigrants (43% and 50%), and racial diversity (41% and 36%) among their top three most important values.

Support for Policies That Would Compensate Descendants for Past Harm

Mortgage Assistance

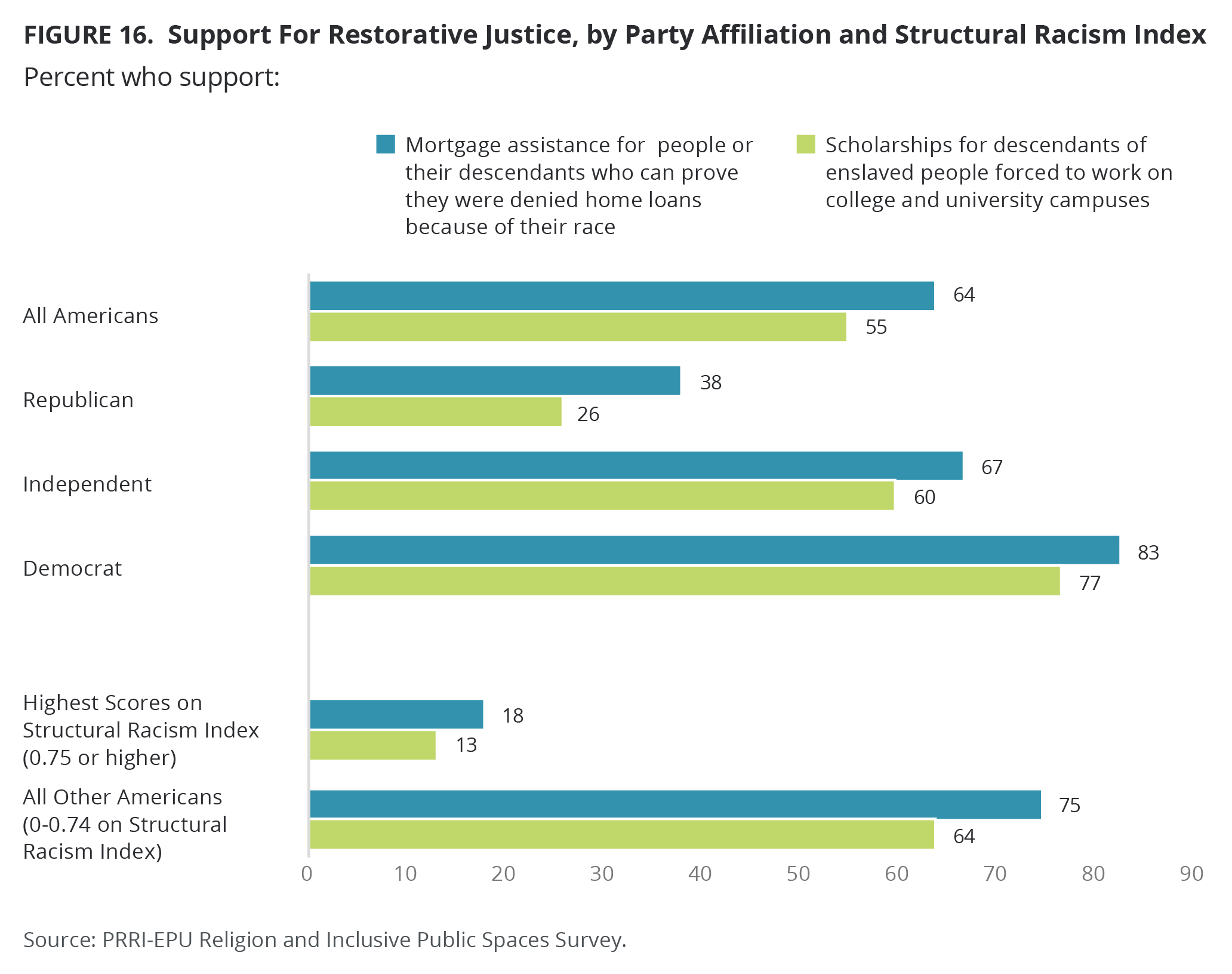

Nearly two-thirds of Americans (64%) favor the idea of local governments providing mortgage assistance for people or descendants of people who can prove they were denied home loans because of their race, including one in four who strongly favor it (25%). Less than one third oppose such a policy (31%).

Only about four in ten Republicans (38%) agree with this idea, compared with more than eight in ten Democrats (83%). Independents fall in between, at 67%.

Black Protestants (83%) are the most likely to agree, followed by Hispanic Catholics (78%), the religiously unaffiliated (73%), and members of other non-Christian religions (72%).[8] White Christian groups have the lowest rates of agreement, including 59% for white mainline Protestants, 54% for white Catholics, and 44% for white evangelical Protestants.

Nearly six in ten white Americans (59%) favor this idea, compared with larger majorities of AAPI (70%), Hispanics (74%), and Black Americans (81%). However, white Americans with a college degree are notably more likely than white Americans without a college degree to be in favor (66% vs. 53%).[9]

There is an inverse relationship between scores on the structural racism index and support for this mortgage assistance policy. When Americans who score the highest on the index are excluded, majorities of all other groups favor a mortgage assistance policy for those who were discriminated against on the basis of race. But among Americans who score 0.75 or higher on the structural racism index, only about one in five (18%) favor mortgage assistance for past discrimination.

Scholarships for Colleges and Universities

A majority of Americans (55%) favor colleges and universities providing scholarships for descendants of enslaved people who were forced to construct buildings and work on their campuses, compared with 41% who oppose such actions. Democrats (77%) are three times as likely as Republicans (26%) to favor these efforts, while independents fall in between (60%).

White Christian groups are the least likely to favor this idea, with only 46% of white mainline Protestants, 44% of white Catholics and 35% of white evangelical Protestants expressing support. At least six in ten Black Protestants (75%), Hispanic Catholics (72%), religiously unaffiliated people (64%), and members of other non-Christian religions (63%) favor this idea.[10]

About half of white Americans (48%) favor these scholarships, compared with solid majorities of Black Americans (68%) and Hispanic Americans (70%). However, white Americans with a college degree are notably more likely than white Americans without a college degree to favor the idea (58% vs. 42%).[11]

There is a strong negative correlation between scores on the structural racism index and support for these efforts. Strong majorities of Americans who score on the lower half of the structural racism index support colleges and universities providing scholarships for descendants of enslaved people, but support drops to approximately one in three among those who score on the higher half of the structural racism index.

Appendix A. Definitions of Monument Typology

Supporters of monument reform

- Agree with the statement “We should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces” AND;

- Say both Confederate flags and monuments are symbols of racism AND;

- Say Confederate statues and memorials should be removed and either put in a museum or destroyed.

Opponents of monument reform:

- Disagree with the statement “We should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces” AND;

- Say both Confederate flags and monuments are symbols of Southern pride AND;

- Say Confederate statues and memorials should be kept in place as they are.

Those with mixed views who lean toward supporting reform:

- Are not in either the full supporter or the full opponent group and fall into one of the following response patterns:

- Agree with the statement “We should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces.”

- Say Confederate monuments should be left in place but have information added about the history of slavery and racism AND see both Confederate flags and monuments as symbols of racism.

Those with mixed views who lean toward opposing reform:

- Are not in either the full supporter or full opponent group and fall into one of the following response patterns:

- Say Confederate statues and memorials should be kept in place as they are.

- Say Confederate monuments should be left in place but have information added about the history of slavery and racism AND disagree with the statement “We should not memorialize historical figures who supported the Confederacy or racial segregation in public spaces.”

- Say Confederate monuments should be left in place but have information added about the history of slavery and racism AND see Confederate flags and monuments as Southern pride.

Appendix B. Output Variables for Regression Model Predicting Support for Monument Reform

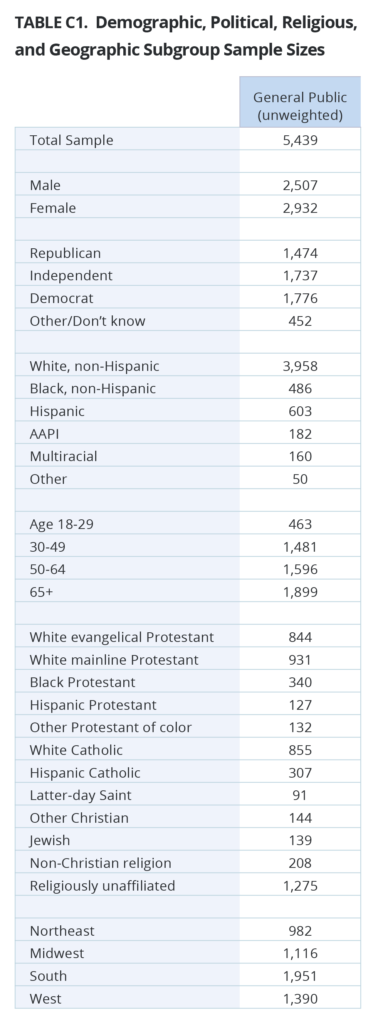

Appendix C. Survey Methodology

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. The survey was made possible through the generous support of the Mellon Foundation. The survey was conducted among a representative sample of 5,021 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States, who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 418 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Interviews were conducted online between June 10 and 29, 2022.

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI. The survey was made possible through the generous support of the Mellon Foundation. The survey was conducted among a representative sample of 5,021 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States, who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 418 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. Interviews were conducted online between June 10 and 29, 2022.

Respondents are recruited to the KnowledgePanel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS – a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

The initial sample drawn from the KnowledgePanel was adjusted using pre-stratification weights so that it approximates the adult U.S. population defined by the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey. Next, a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling scheme was used to select a representative sample.

To reduce the effects of any non-response bias, a post-stratification adjustment was applied based on demographic distributions from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS). The post-stratification weight rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, Census division, metro area, education, and income. The sample weighting was accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights were trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results. In addition to an overall national weight, separate weights were computed for each state to ensure that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. The state-level post-stratification weights rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, and income.

The margin of error for the national survey is +/- 1.7 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence, including the design effect for the survey of 1.6. In addition to sampling error, surveys may also be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects. Additional details about the KnowledgePanel can be found on the Ipsos website: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solution/knowledgepanel

Endnotes

[1]The methodology for creating the Structural Racism Index was first developed in PRRI President Robert P. Jones’s 2020 book “White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity,” using data collected in PRRI’s 2018 American Values Survey. The Structural Racism Index created here uses seven of the original fifteen questions, plus four new questions. Because the question battery has changed, trends are not directly comparable. Only respondents who completed at least six of the 11 items are included in the scale, n=5,317. The 11 questions have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93, indicating that responses are highly correlated and scaling is appropriate.

[2]For the purposes of this report, the South is defined as the 13 key states for this project: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

[3]The number of cases for AAPI and multiracial Americans is too small to report in this section since the questions were only asked of half the sample.

[4]The dependent variable is the full support group. The table in this section shows all statistically significant results. Full regression output results can be found in the table in the appendix.

[5] Mainstream outlets include NBC, CBS, ABC, CNN, MSNBC, local broadcast news, and public television.

[6] The number of cases for Latter-Day Saints and Americans of other race categories by education is too small to report.

[7] The number of cases for these groups for the statement “efforts that reconfigure or reimagine public spaces so they better represent everyone in your community” is too small to report since the question was only asked of half the sample.

[8] The number of cases for Hispanic Protestants, other Christians, other Protestants of Color, Latter-Day Saints and Jewish Americans is too small to report.

[9] The number for multiracial Americans and Americans of color by education is too small to report for this question.

[10] The number of cases for Hispanic Protestants, other Christians, other Protestants of Color, Latter-Day Saints and Jewish Americans is too small to report.

[11] The number for multiracial Americans, AAPI, and Americans of color by education is too small to report for this question.