Listening to conservative religious commentators or even popular LGBTQ media outlets, you might be hard-pressed to find references to religious LGBTQ people. Most of the time, media, religious, and even scientific discourse relies on what I refer to as the Will & Grace paradigm to both depict and evaluate LGBTQ culture. In short, this means popular portrayals and social scientific theories about LGBTQ behavior rest on the assumption that white, wealthy, urbanite, non-religious gay cisgender men are the paradigm of the social category we call LGBTQ. This cannot be further from the truth.

LGBTQ people, especially LGBTQ people of color and transgender people, are more likely to live in poverty than heterosexual and cisgender people are. An increasing proportion of LGBTQ people live in rural areas, especially LGBTQ people with families, who disproportionately live in the southern United States. Furthermore, an increasing proportion of young LGBTQ people identify as nonbinary or bisexual.

Many LGBTQ people are religious. While the importance of religion among LGBTQ people as well as the degree of participation in organized faith traditions are lower among them than among heterosexuals, the proportion of LGBTQ people who both identify with a faith tradition and look to that tradition for guidance in their lives is not insignificant. There are significant differences in which traditions LGBTQ people look to, however.

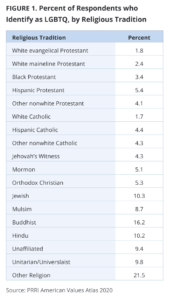

PRRI’s 2020 American Values Atlas (AVA), for example, shows both the diversity of religious experiences among LGBTQ people and also some significant differences between LGBTQ people’s religious affiliations and those of other members of the general population. For example, while about five percent of Americans identify as LGBTQ in the 2020 AVA, about 16% of Buddhists and 10% of Hindus and Jews identify as LGBTQ. On the other hand, about two percent of white mainline (non-evangelical) Protestants, about three percent of Black Protestants, and about five percent of Hispanic Protestants identify as LGBTQ. Less than two percent of white Evangelicals identify as LGBTQ.

So what does all of this mean for politics and policy? First, as I wrote in 2018, religious belief and participation acts as a political resource for LGBTQ people. That is, religiously active LGBTQ people are more likely to participate in politics than non-religiously active LGBTQ people. This is consistent with both contemporary and historical trends in LGBTQ politics.

Since the 1960s, LGBTQ people and their allies have democratized existing religious spaces and even created their own when necessary. Some early organizations like the Council on Religion and the Homosexual sought to educate clergy about the LGBT community. Others, like the Metropolitan Community Church and Unity Fellowship Movement, sought to uplift LGBTQ people who were rejected by their religious communities. Since the 1970s, numerous local congregations and whole denominations have undertaken efforts to become more open and/or affirming with regard to the full participation of LGBTQ members and leaders. In short, the opportunities for LGBTQ people to express their faith and participate within faith communities in the United States have multiplied.

These are not just social or spiritual opportunities, however. Remember, religious participation can facilitate political participation. Why? One theory holds that religiously active people gain specific skills and knowledge that can help them translate their volunteerism into political activism. Another theory holds that religious organizations recruit political participants like they do any other interest group. Still another theory holds that for marginalized people, organizations that offer community connectedness (think religious communities formed by immigrant communities, predominantly African American churches and, yes, LGBTQ community organizations) also foster political activism as members learn about their marginalization, the power of collective action, and the source of their marginalization.

I tested this theory using data from a representative sample of LGBTQ people in the United States. The sample was recruited from Qualtrics, Inc., between November 4 and 14, 2016; while it was not a random sample, I established demographic quotas based on two probability samples of LGBTQ Americans in order to make the sample as representative as possible.

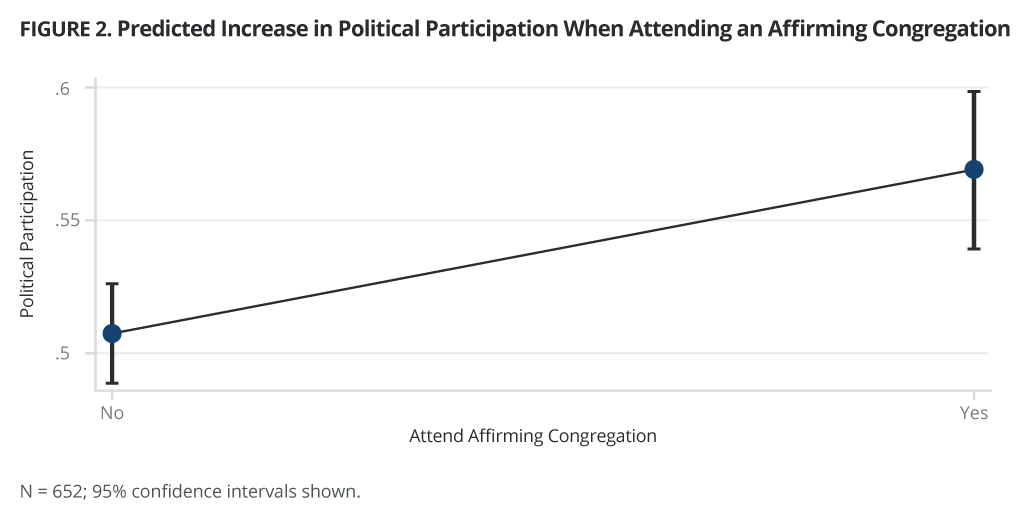

I asked respondents several questions about their LGBTQ identity, their religious affiliation, and whether or not they attended a religious congregation that affirms their LGBTQ identity. I designed the study specifically to determine if political participation differs among religiously active LGBTQ people based on whether or not their religious congregation is “open” or “affirming.” It appears that it does. In short, LGBTQ people who attend a religious congregation that affirms their identity are more likely to engage in political activism than LGBTQ people who do not attend these congregations.

As Figure 2 shows, after controlling for other potential influences, including religious tradition, age, education, income, urban residency, ethnicity, gender, and measures of LGBTQ identity, religiously active LGBTQ people in affirming congregations are more likely to participate in a variety of political activities. Although only shown in the aggregate here, the association holds for voting in primary elections, donating money, volunteering for campaigns, and attending political rallies.

These results are from an exploratory analysis, and there is still a lot we do not know. For example, are religiously active LGBTQ people attending affirming congregations because they are more politically active? I cannot answer that question with these data. But this leads to another important point about how social science is failing religious LGBTQ populations. Because many researchers have been trained under them Will & Grace paradigm, they often do not think to ask LGBTQ people about their religious experiences when designing surveys. So we are often left with an incomplete picture of the lives and experiences of LGBTQ people.

R. G. Cravens III is a member of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.