I. Social Group Affinity and Feelings about Young People

Social Group Affinity

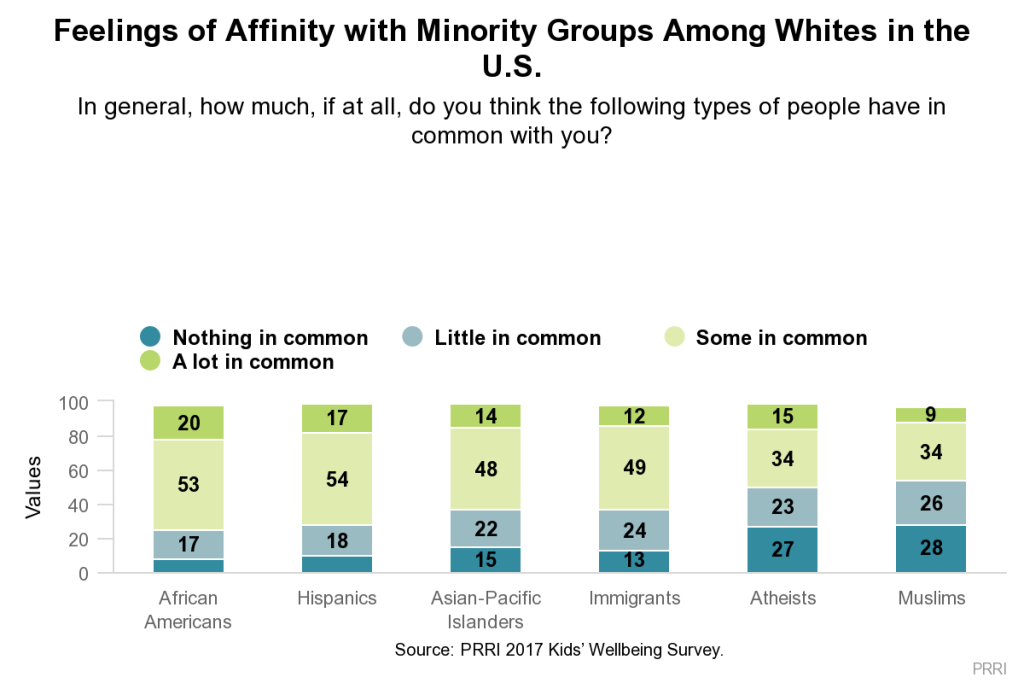

Most white Americans report feeling at least some affinity with members of racial, ethnic, and religious minority communities although relatively few say they have a lot in common. Nearly three-quarters of white Americans say they have either a “lot” (20%) or “some” (53%) in common with African Americans. Similar numbers of whites say they have a lot (17%) or some (54%) in common with Hispanic Americans. Fewer whites report the same with Asian and Pacific-Islander Americans (14% say “a lot” and 48% say “some) or immigrants (12% say “a lot” and 49% say “some” in common). Only 43% of whites, however, say they have a lot or some in common with Muslims, and 49% of whites—including only 39% of white Christians—say they have a lot or some in common with atheists.

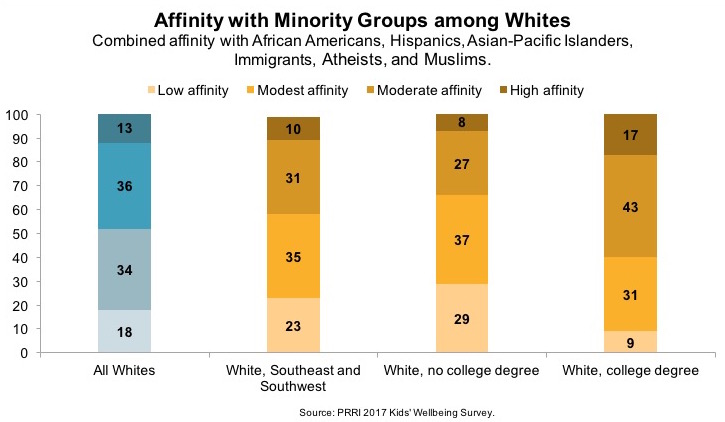

To provide an overall picture of the degree of affinity that white Americans express towards a variety of different groups, we developed the “Group Affinity Scale” by combining responses to all s. questions.1 More than half of white Americans report having “low” (18%) or “modest” (34%) affinity for people of different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. More than one-third (36%) report having “moderate” affinity for these groups, while 13% feel “high” affinity toward them.

To provide an overall picture of the degree of affinity that white Americans express towards a variety of different groups, we developed the “Group Affinity Scale” by combining responses to all s. questions.1 More than half of white Americans report having “low” (18%) or “modest” (34%) affinity for people of different racial, religious, and ethnic backgrounds. More than one-third (36%) report having “moderate” affinity for these groups, while 13% feel “high” affinity toward them.

There are considerable differences among whites by educational attainment. Nearly two-thirds of whites with a college degree have a moderate (45%) or high degree (19%) of affinity toward people of different racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds. Fewer than half of whites without a college degree have a moderate (31%) or high (10%) affinity for such groups.

There are substantial partisan divisions among white Americans on the question. A majority of white Democrats have a moderate (39%) or high (18%) affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups. More than half of white independents also report a moderate (37%) or high affinity (14%). In contrast, only about one-third of white Republicans report having either moderate (29%) or high affinity (6%) for these groups.

The demographic profile of whites with a low affinity for religious, racial, and ethnic minority groups is quite distinct from those who have a high degree of affinity. First, whites with low affinity are somewhat older: A majority (56%) are age 50 or older, compared to 46% of those who have high affinity. A majority (57%) of whites with low affinity have a high school degree or less, compared to only 19% of whites with high affinity. Only 13% of those whites with a low affinity to minority groups have a college degree compared to nearly half (48%) of whites with a high affinity. The ideological outlook of whites also varies between those with a low and high affinity for minority groups. Close to half (46%) of whites with a high affinity identify as liberal, compared to only 11% of those expressing very low levels of affinity.

The demographic profile of whites with a low affinity for religious, racial, and ethnic minority groups is quite distinct from those who have a high degree of affinity. First, whites with low affinity are somewhat older: A majority (56%) are age 50 or older, compared to 46% of those who have high affinity. A majority (57%) of whites with low affinity have a high school degree or less, compared to only 19% of whites with high affinity. Only 13% of those whites with a low affinity to minority groups have a college degree compared to nearly half (48%) of whites with a high affinity. The ideological outlook of whites also varies between those with a low and high affinity for minority groups. Close to half (46%) of whites with a high affinity identify as liberal, compared to only 11% of those expressing very low levels of affinity.

The Southeast/Southwest

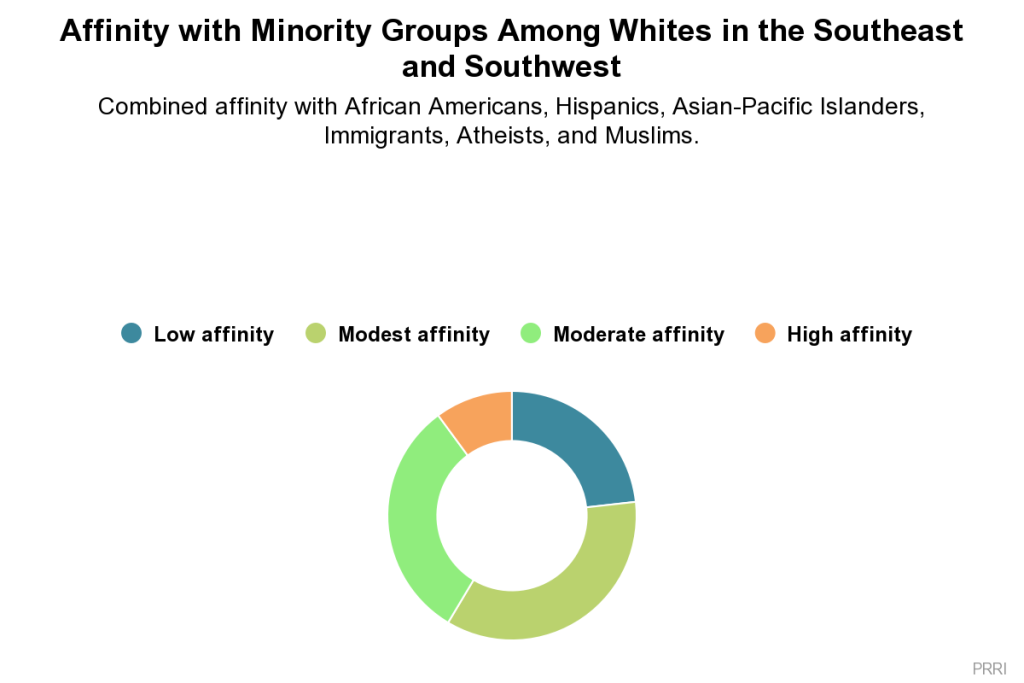

Overall, whites in the Southeast and Southwest region have somewhat less affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups.2 Nearly six in ten whites in these regions have low (23%) or modest (35%) affinity, while about four in ten express moderate (31%) or high affinity (10%).

However, more educated whites in these regions express greater affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups than whites who are less educated. Six in ten whites with a college education express a moderate (43%) or high affinity (17%) for people of different racial, ethnic, and religious backgrounds. Only about one-third of whites without a college degree feel a moderate (27%) or high (8%) degree of affinity.

Partisan differences are more muted in these regions. Fewer than half of white Democratic residents have a moderate (37%) or high (10%) affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups. Fewer than half of white independents also report a moderate (32%) or high affinity (13%). In contrast, only about one-third of white Republicans in these regions report having either moderate (28%) or high affinity (6%) for these groups.

The Values and Economic Importance of Young People

Americans generally agree that the future economic success of the United States is dependent on helping minority children succeed. More than three-quarters (77%) of Americans agree that as the number of black and minority children continues to grow, our economic future depends on helping children from these communities be successful.

There is consensus on this issue across racial and ethnic groups. More than three-quarters of white (76%), Hispanic (79%), and black Americans (82%) also endorse the view that the country’s economic future is dependent on helping minority children succeed. Both whites with high and low affinity for minority groups agree that helping minority children is imperative (83% vs. 74%). However, low-affinity whites are about half as likely as high-affinity whites to strongly embrace this belief (25% vs. 49%).

However, most Americans perceive a disconnect between their own values and those of young people. Three-quarters (75%) Americans agree “most young people today do not share the same values I do.”

This view is shared across different racial and ethnic groups. More than eight in ten (85%) black Americans and more than seven in ten white (76%), and Hispanic Americans (73%) say young adults do not share their values.

The disconnect is felt across the political spectrum, although Republicans (87%) are more likely than Democrats (64%) to perceive a values gap between themselves and young adults. Independents largely mirror the general public.

The Southeast and Southwest

Roughly three-quarters (76%) of residents of the Southeast and Southwest regions believe the country’s future is dependent on the success of minority children. Similar numbers of white (74%), Hispanic (74%), and black residents (83%) endorse this view.

Again, political affiliation sees the largest divides on this question. A 20-point gap separates Democrats (84%) and Republicans (64%), although majorities of both groups agree helping minority children is critical to the country’s economic future.

At the same time, residents of the Southeast and Southwest also perceive a sizable gap between their own values and those of young people. Nearly eight in ten (79%) say their values do not align with those of young people today.

Similar numbers of black (83%), white (79%), and Hispanic residents (78%) say their values are largely different from the values of young people today. Among whites, those without a college degree (83%) are more likely than those with a college degree (68%) to perceive differences. Further, whites who express low affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups are far more likely than those with high affinity to believe that young people’s values do not align with their own (91% vs. 58%, respectively).

II. Optimism About the Country’s Future

Are the Country’s Best Days Ahead of or Behind Us?

Americans are about evenly divided on the question of whether the country’s best days are still to come. A majority (52%) of Americans believe the country’s best days are ahead of us, while close to half (46%) say they are behind us.

Racial differences on this issue are stark. Majorities of white (54%) and Hispanic (52%) Americans say America’s best days are still to come, while fewer than four in ten (39%) black Americans feel the same. Whites with a college degree have a somewhat more positive outlook about the future than those without (58% vs. 52%, respectively).

Party differences in optimism about the country are also strong. Roughly two-thirds of Republicans (64%) say America’s best days are still to come, while only 45% of Democrats feel the same. Independents (53%) fall between these two groups. Optimism among partisans has shifted over the past couple of years. In 2015, nearly six in ten (59%) Democrats reported feeling that America’s best days are yet to come while only about four in ten (41%) Republicans expressed this view.3

A majority (54%) of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions believe America’s best days are yet to come. Close to half (45%) say America’s best days are in the past. The demographic patterns in these regions are nearly identical to those seen at the national level.

Concerns Over the Next Generation’s Wellbeing

The general public is split over whether most children growing up today will be better or worse off than their parents. Nearly half (48%) of Americans say most children will grow up to be better off than their parents, while 50% say most children will grow up to be worse off.

Notably, racial differences on the optimism about the future of the country itself do not extend to optimism about the next generation’s wellbeing. Only about half of white (47%), black (48%), and Hispanic Americans (51%) say children will be better off than their parents.

There are modest political differences in optimism about the future of America’s children. A majority (54%) of Republicans believe children in the U.S. are likely to grow up to be better off, compared to fewer than half of independents (47%) and Democrats (46%). There are no major differences across educational, age, or gender groups in views about the future welfare of children.

Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions of the U.S. express nearly identical views as Americans overall. Close to half (47%) of Americans living in these regions say children will be better off than their parents, while a majority (52%) say they will be worse off.

Although there are no generational differences nationally, seniors (age 65 or older) living in the Southeast and Southwest are more pessimistic about the welfare of children. Nearly six in ten (58%) say children will be worse off than their parents.

III. Opportunity and Success

Equal Opportunity

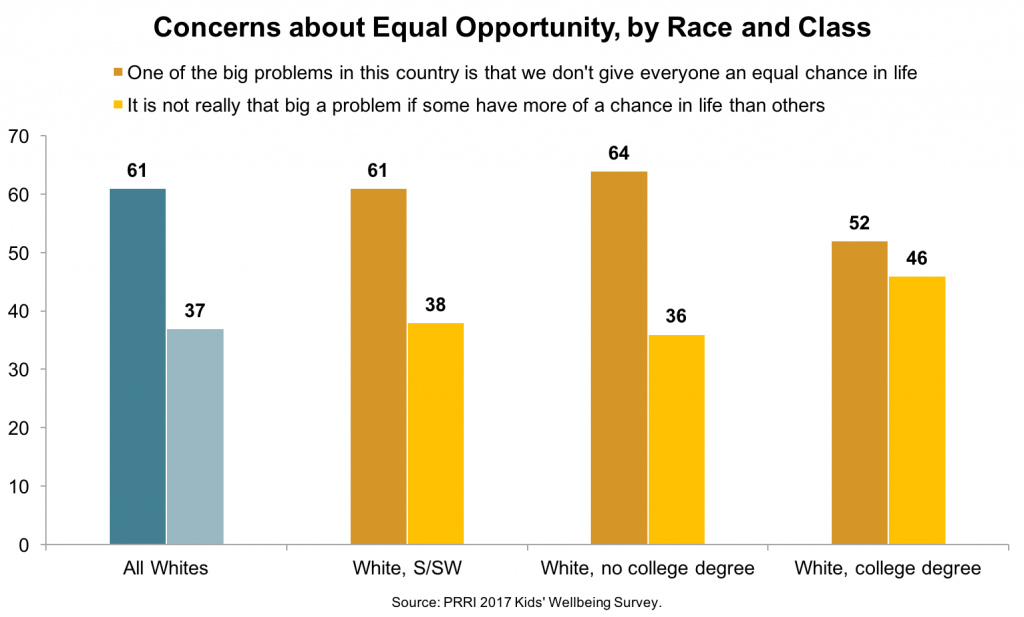

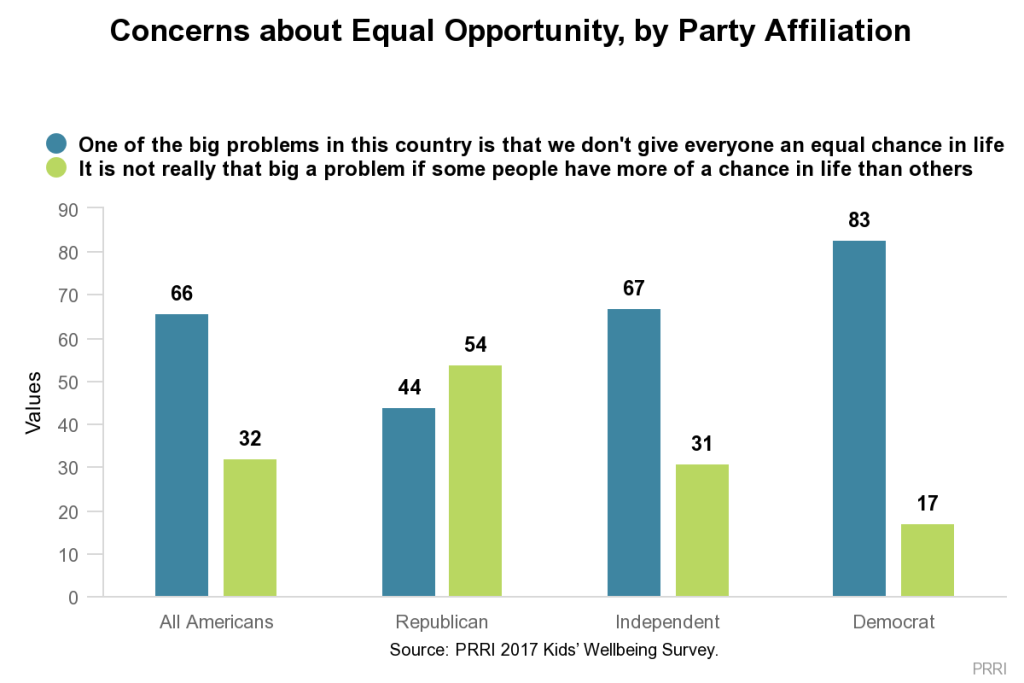

Americans are broadly concerned about equal opportunity in the country. Roughly two-thirds (66%) of Americans believe that “one of the big problems in this country is that we don’t give everyone an equal chance in life,” while only 32% agree that “it is not really that big a problem if some have more of a chance in life than others.”

There is general agreement across major racial and ethnic groups that a lack of equal opportunity is a significant problem in the U.S., although there are differences in the level of concern. More than eight in ten (83%) black Americans, nearly three-quarters (74%) of Hispanic Americans, and roughly six in ten (61%) white Americans say one of the big problems in the U.S. is that not everyone has an equal chance to succeed in life.

White college-educated Americans express less concern about the lack of opportunity than those without a college degree (56% vs. 63%, respectively). But high-affinity whites are about as likely as those with low affinity to express concerns about lack of opportunity (68% vs. 65%, respectively).

White college-educated Americans express less concern about the lack of opportunity than those without a college degree (56% vs. 63%, respectively). But high-affinity whites are about as likely as those with low affinity to express concerns about lack of opportunity (68% vs. 65%, respectively).

There are significant differences across the political spectrum about the extent to which lack of equal opportunity is a problem. More than eight in ten (83%) Democrats believe that not giving everyone an equal chance in life is a major problem in the U.S., while fewer than half (44%) of Republicans agree. A majority (54%) of Republicans say that it is not really a problem if some have more of a chance in life than others. Independents largely reflect the views of Americans overall.

Concerns about inequality also vary significantly across lines of gender. Men are less likely than women to say that not giving everyone an equal shot is a major problem in the country (59% vs. 73%, respectively).

Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest mirror the views of the public overall. Nearly two-thirds (65%) say that not providing everyone an equal chance is a major problem.

More than eight in ten (81%) black residents and about six in ten Hispanic (63%) and white residents (61%) of these regions say the lack of equal opportunity is a substantial problem.

Opportunities for Success

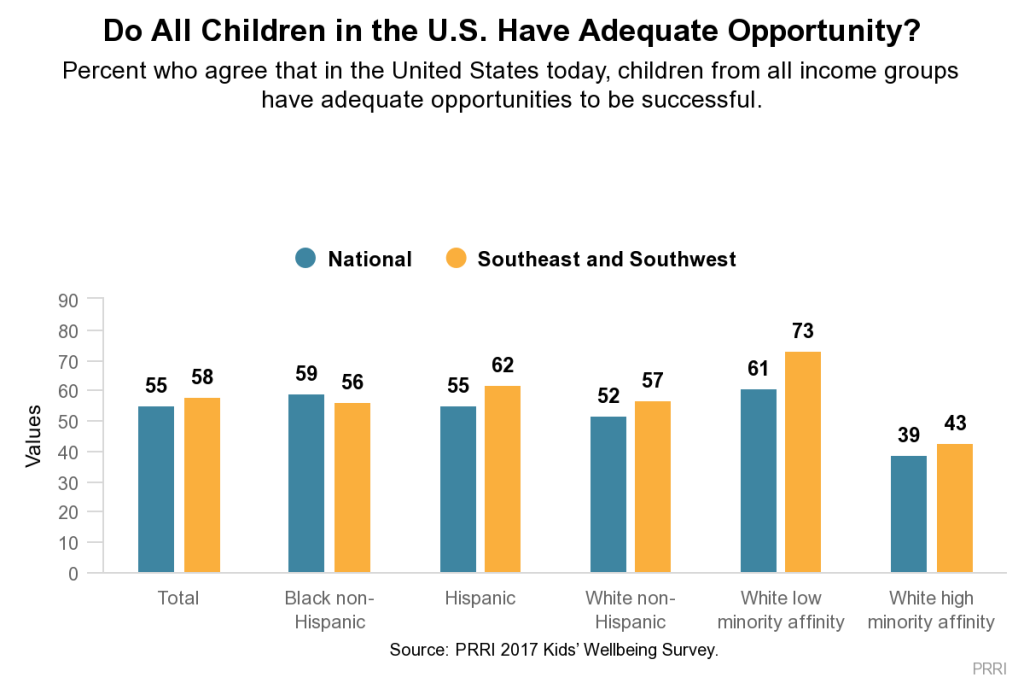

Americans report considerable concern about lack of opportunity in the U.S., but there is disagreement over whether all children have opportunities to be successful. A majority (55%) of Americans agree children from all income groups have adequate opportunities to be successful, while 45% disagreed with this statement.

Racial gaps in perceptions that all children are given adequate chances are fairly modest. A majority of black (59%), Hispanic (55%), and white Americans (52%) agree children from different social classes have adequate opportunities to be successful. Interestingly, whites without a college degree are much more optimistic about the opportunities available to children across the income spectrum. A majority (57%) of whites without a college degree say children of all socio-economic backgrounds have adequate opportunities to be successful, a view shared by only 43% of whites with a college degree. Whites with a low affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minorities are also much more likely than those with a high affinity to say there are adequate opportunities for children to succeed (61% vs. 39%, respectively).

Responses to this question again divide sharply along party lines. Roughly two-thirds (66%) of Republicans say children from all income groups have adequate chances, while fewer than half (44%) of Democrats agree. The gap between those who voted for President Donald Trump and those who voted for Hillary Clinton is even greater: 70% of Trump supporters believe all children have adequate opportunities, while only 41% of Clinton supporters say the same.

Responses to this question again divide sharply along party lines. Roughly two-thirds (66%) of Republicans say children from all income groups have adequate chances, while fewer than half (44%) of Democrats agree. The gap between those who voted for President Donald Trump and those who voted for Hillary Clinton is even greater: 70% of Trump supporters believe all children have adequate opportunities, while only 41% of Clinton supporters say the same.

A similar number (58%) of Americans living the Southeast and Southwest believe children of different income brackets have adequate opportunities. This view is generally shared equally among Hispanic (62%), white (57%), and black residents (56%). However, white residents in these regions without a college degree are more likely than those with a college degree to believe there are adequate opportunities (60% vs. 51%, respectively). There is an even larger affinity gap among whites in these regions—nearly three-quarters (73%) of those with a low affinity say children have suitable opportunities compared to roughly four in ten (43%) whites with a high affinity.

Factors that Affect Success

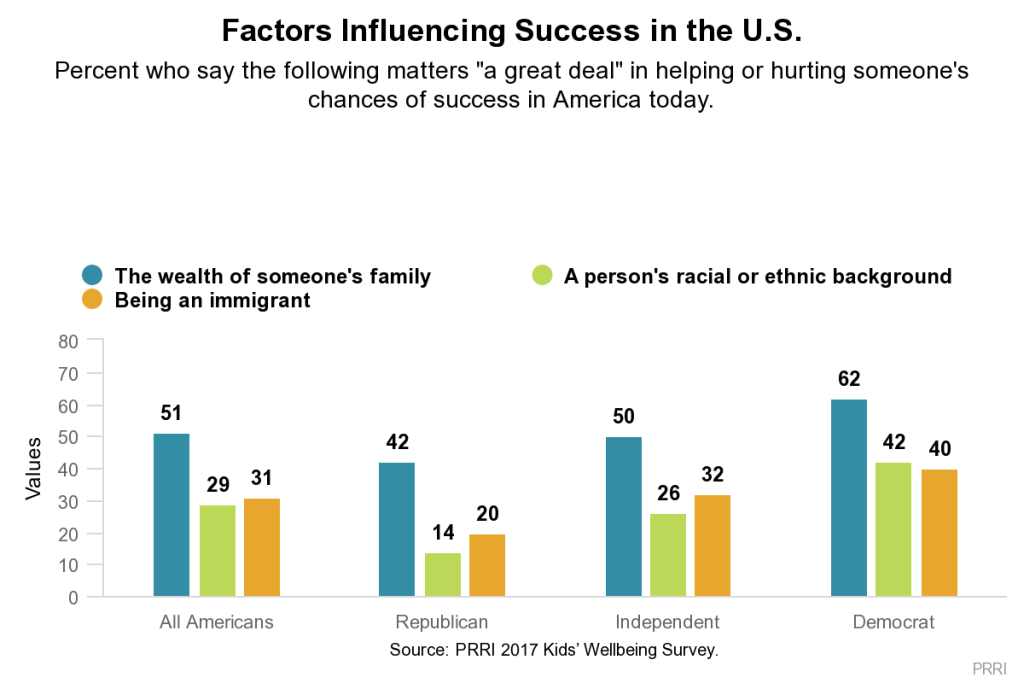

Americans generally agree that there are several factors beyond one’s own merit and hard work that either help or hurt people in their efforts to get ahead. A majority of Americans believe family wealth, racial and ethnic identity, and immigrant status impact the prospects of success.

Family Wealth

A slim majority (51%) of Americans say family wealth matters “a great deal,” while 28% say it matters to some extent. Just 21% of the public report that family wealth matters “little” or “not at all.”

Agreement on this issue extends across racial and ethnic groups, although white Americans (53%) are slightly more likely than black (48%) and Hispanic Americans (48%) to say someone’s family wealth matters a great deal in determining their chances for success. Notably, whites with a low affinity for minority groups are far less likely than those with a high affinity to believe that family wealth matters a great deal (47% vs. 72%, respectively).

There are greater partisan divides on how family wealth impacts success. Democrats (62%) are much more likely than independents (50%) or Republicans (42%) to say that family wealth matters “a great deal.”

Interestingly, there are no significant differences by income. A majority of Americans with household incomes under $30,000 per year and those with incomes in excess of $100,000 say that family wealth matters a great deal (51% vs. 57%, respectively).

Interestingly, there are no significant differences by income. A majority of Americans with household incomes under $30,000 per year and those with incomes in excess of $100,000 say that family wealth matters a great deal (51% vs. 57%, respectively).

White evangelical Protestants (42%) are less likely than other religious Americans to say family wealth matters a great deal. Sixty-three percent of the religiously unaffiliated and at least half of white mainline Protestants (50%), black Protestants (52%), and Catholics (51%) believe family wealth plays an important role in determining one’s chances. Notably, white Catholics are significantly more likely than Hispanic Catholics (55% vs. 45%, respectively) to believe in the role that family wealth plays.

The attitudes of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions match those of the country overall. A slim majority (51%) say an individual’s family wealth matters a great deal. There are no major differences of opinion between residents of different racial, ethnic, or educational backgrounds.

Racial or Ethnic Background

Compared to family wealth, significantly fewer Americans agree that a person’s racial or ethnic background plays much of a role in determining an individual’s success. Fewer than one in three (29%) say a person’s race or ethnic background matters a great deal. Roughly four in ten (38%) say it matters some, while about one-third report that this personal attribute matters little (16%) or not at all (16%).

Not surprisingly, there are sizable racial differences on this issue—though there is no major racial or ethnic group in which a majority believes a person’s racial or ethnic background plays a large role in success. Nearly half (46%) of black Americans, and only 33% of Hispanics, and 25% of whites, believe that racial and ethnic background matters a great deal. Importantly, whites with high affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minorities are not much more likely than low-affinity whites to see a link between a person’s racial or ethnic background and their chances of being successful in the U.S. (34% vs. 25%, respectively).

There are also significant differences in the perceived importance of racial background between partisans. Democrats (42%) are three times as likely as Republicans (14%) to believe racial background matters a great deal for success. Forty-five percent of Republicans—but only 23% of Democrats—say racial background matters very little or not at all.

Fewer than one in three (29%) residents of the Southeast and Southwest believe a person’s racial or ethnic background impact their chances of getting ahead. Black residents (54%) are far more likely to say a person’s racial or ethnic background matters “a great deal” than Hispanic (28%) or white residents (22%).

Immigration Status

A similar number of Americans believe immigration status impacts one’s chances of getting ahead in life. Roughly three in ten (31%) believe it matters a great deal for one’s chances of getting ahead in life. Approximately four in ten (38%) report that immigrant status matters some while fewer than one-third say it matters a little (16%) or not at all (13%).

There is a significant disparity between black, white, and Hispanic Americans about the role that immigration status plays in achieving success in American society. Hispanics (43%) are more likely than black (35%) and white Americans (27%) to believe that being an immigrant matters a great deal for one’s ability to get ahead. Among whites, there are no significant differences between those with a high and low affinity.

Opinions on the role of immigration status also diverge sharply by party affiliation, with Democrats (40%) more likely than either independents (32%) or Republicans (20%) to say that being an immigrant matters a great deal.

In the Southeast and Southwest regions, one-third (33%) of residents say someone’s immigration status has a major impact on their chances of success. Black (43%) and Hispanic residents (39%) are more likely to believe this than white residents (27%).

Children Living in Poverty

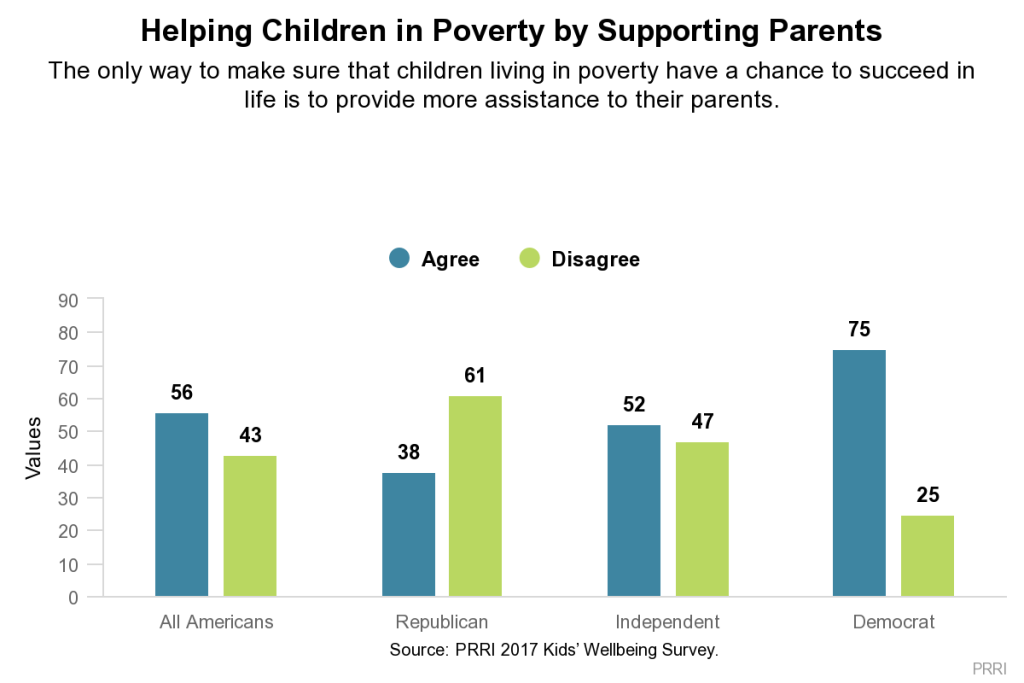

A majority (56%) of Americans endorse the belief that the only way to help children escape poverty is to provide more assistance to their parents. More than four in ten (43%) Americans disagree with this statement.

White Americans are significantly less likely than other racial and ethnic groups to think that assisting parents is critical to helping low-income children succeed. Whites are divided over whether providing more help to parents is the best way to help children escape poverty: 48% agree and 51% disagree. In contrast, more than seven in ten black (78%) and Hispanic Americans (73%) say parental assistance is critical. Importantly, there is a substantial cleavage of opinion among white Americans.

White young adults (age 18-29) are much more likely than white seniors (age 65 or older) to say that helping parents is the only way to provide low-income children a path to succeed (57% vs. 42%, respectively).

There are also strong partisan divisions. Only about four in ten (38%) Republicans agree with the idea that family assistance is the only way to help children out of poverty, while a majority (52%) of independents and three-quarters (75%) of Democrats say the same.

There are also strong partisan divisions. Only about four in ten (38%) Republicans agree with the idea that family assistance is the only way to help children out of poverty, while a majority (52%) of independents and three-quarters (75%) of Democrats say the same.

Nearly six in ten (57%) residents of the Southeast and Southwest regions say providing additional assistance to parents is the best way to help children escape poverty. Whites in these regions are closely divided: 48% agree with the statement and 51% disagree. More than three-quarters (76%) of black residents and more than two-thirds (68%) of Hispanic residents in the Southeast and Southwest believe parental assistance is pivotal.

IV. Cultural Anxiety

Discomfort with Non-English Speakers

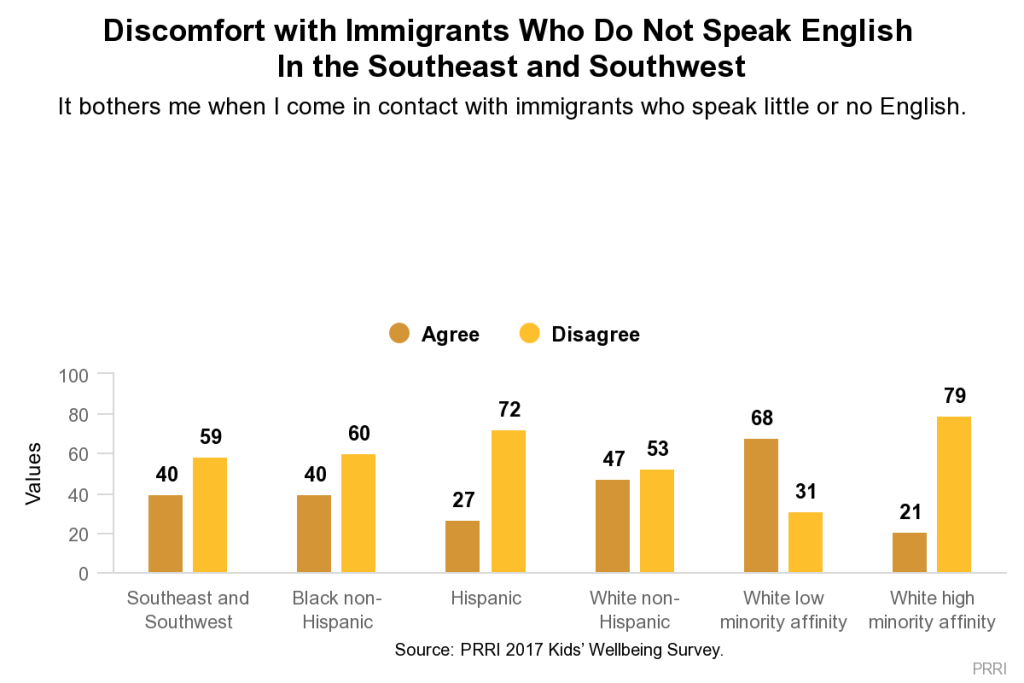

A majority (59%) of Americans say they are not bothered when they come into contact with immigrants who speak little to no English, while four in ten (40%) say they are bothered during these interactions.

Views about immigrants vary markedly by race and ethnicity. Only 22% of Hispanic Americans, but 41% of black Americans and 45% of white Americans, report being bothered by coming into contact with immigrants who speak no English. There are considerable differences of opinion among whites by social affinity. Low-affinity whites are roughly five times more likely than high-affinity whites to report being bothered when interacting with non-English-speaking immigrants (66% vs. 13%, respectively).

Differences along partisan lines are also significant: Six in ten (60%) Republicans, but only 36% of independents and 29% of Democrats, are bothered by such interactions.

Southeast and Southwest

An identical number (59%) of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions also say they are not bothered when they come into contact with immigrants who speak little or no English; 40% say it would bother them.

Racial differences seen among Americans in the Southeast and Southwest regions mirror those nationally. Nearly half (47%) of whites and four in ten (40%) black Americans say that contact with non-English speaking immigrants bothers them, compared to roughly one-quarter (27%) of Hispanics in these regions. White residents with a college degree are significantly less likely to be bothered by interactions with non-English speaking immigrants than those without a college degree (38% vs. 49% respectively). There is a similar gaping difference in attitudes of high- and low-affinity whites in these regions. Nearly seven in ten (68%) low-affinity whites, compared to 21% of high-affinity whites, say it bothers them when they come into contact with immigrants who do not speak English.

Partisan differences are also large in these regions. A majority (55%) of Republicans in these regions are bothered by coming into contact with immigrants who do not speak English, but only 36% of independents and 33% of Democrats feel the same.

Partisan differences are also large in these regions. A majority (55%) of Republicans in these regions are bothered by coming into contact with immigrants who do not speak English, but only 36% of independents and 33% of Democrats feel the same.

Among religious groups these regions, white evangelical Protestants are by far the most likely to be bothered by interactions with non-English speaking immigrants. A majority (57%) of white evangelical Protestants say they are bothered by such interactions, compared to 49% of white mainline protestants, 35% of Catholics, and 29% of those with no religious affiliation.

Stranger in My Own Country

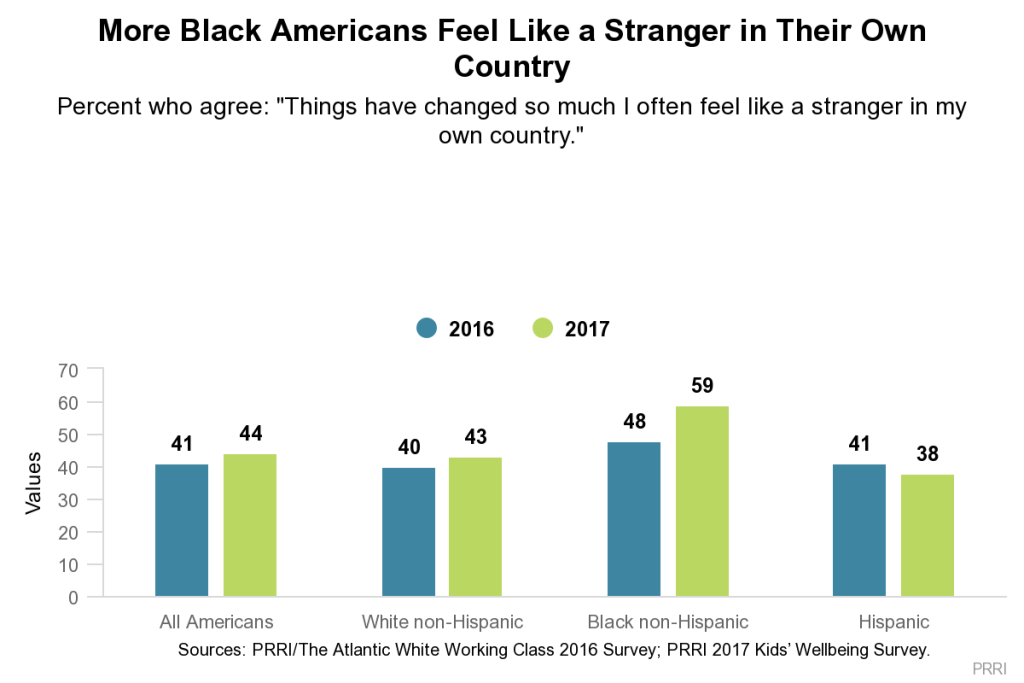

Almost half of Americans (44%) agree that things have changed so much that they often feel like strangers in their own country. A majority (55%) of the public disagrees.

Nationally, black Americans (59%) are significantly more likely than white (43%) or Hispanic Americans (38%) to say they feel like strangers in their own country. Black Americans have become increasingly likely to affirm this statement. In 2016, fewer than half (48%) of black Americans reported that they felt like a stranger in their own country.4 The views of whites did not change over the same time period, with roughly as many (40%) in agreement with the statement last year.

Young people are significantly less likely than older Americans to report that they feel like strangers in their own country. Only about one-third (34%) of Americans under the age of 30 agree with this statement, compared to a majority (53%) of those age 65 or older.

Young people are significantly less likely than older Americans to report that they feel like strangers in their own country. Only about one-third (34%) of Americans under the age of 30 agree with this statement, compared to a majority (53%) of those age 65 or older.

The Southeast and Southwest

Close to half (48%) of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions say they feel like a stranger in their own country. A slim majority (51%) disagree.

There is broader agreement across racial and ethnic groups in these regions. A majority (54%) of black residents and close to half of Hispanic (45%) and white residents (49%) report feeling this way. However, low-affinity whites are far more likely than high-affinity whites to say they feel like a stranger in their own country (71% vs. 27%, respectively).

Both age and education play a strong role in shaping whether the attitudes of whites in the region. A majority (53%) of whites without a college degree say they often feel like a stranger, compared to only 38% of whites with a four-year college education. And while more than half (55%) of white seniors say they often feel like a stranger in their own country, only 39% of white young adults express the same view.

There is surprisingly little difference between partisans. Roughly half of Republicans (52%), independents (48%), and Democrats (48%) in these regions report that they often feel like strangers in their own country.

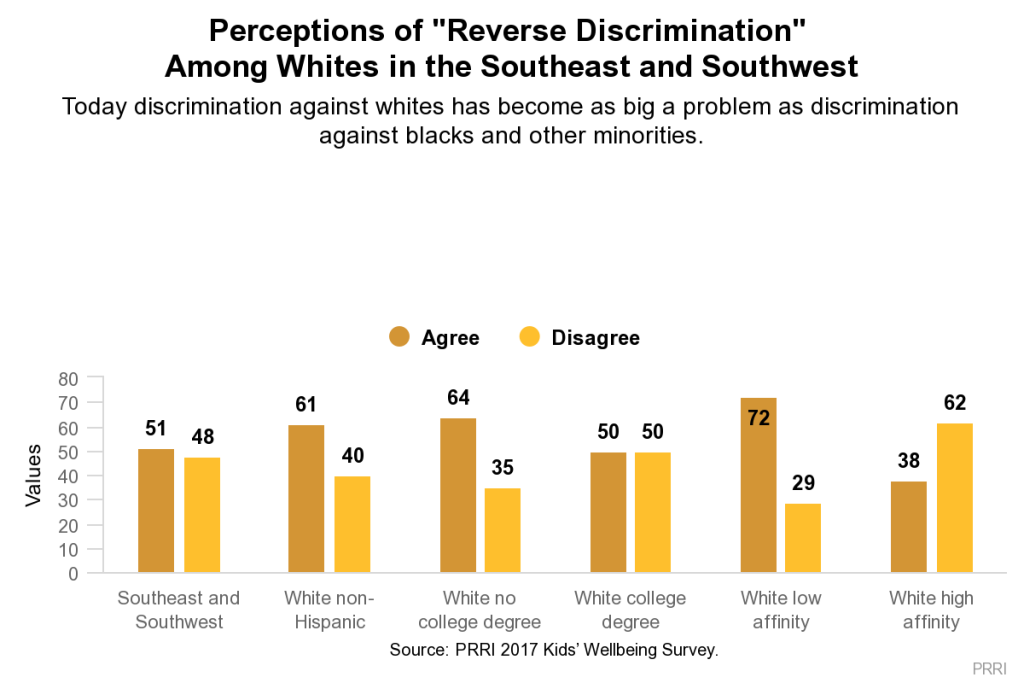

Discrimination Against Whites

Nearly half (48%) of all Americans—and a majority (54%) of white Americans—believe that discrimination against whites has become as big of a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. Only about one-third (36%) of Hispanic Americans and 28% of black Americans agree. Among whites, those who feel a strong affinity to racial, ethnic, and religious minorities are far less likely to express this view than those with weak affinities (30% vs. 69%, respectively).

Nationally, attitudes about “reverse discrimination” are more tied to partisanship than they are to race. Seven in ten (70%) Republicans agree discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against minorities, a view shared by fewer than half (46%) of independents and only about three in ten (31%) Democrats.

White Christians also tend to be much more apt to think that discrimination against whites has become as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities. Roughly two-thirds (66%) of white evangelical Protestants, 56% of white Catholics, and 53% of white mainline Protestants feel this way, compared to fewer than four in ten religiously unaffiliated (36%), Hispanic Catholics (34%), and black Protestants (28%).

The Southeast and Southwest

A slim majority (51%) of Americans in the Southeast and Southwest regions say discrimination against whites is as big of a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities.

Whites in these regions are even more likely to agree that reverse discrimination is a problem. More than six in ten (61%) whites across these regions perceive discrimination against whites to be as big of a problem as discrimination against nonwhites, compared to 40% of Hispanic residents and 32% of black residents. Whites who feel little affinity to minority groups are much more likely to express concerns about reverse discrimination than those who have much greater affinity (72% vs. 38%, respectively).

Among whites in these regions, there are significant age differences in how widely reverse discrimination is perceived as a problem. Only 41% of white residents under the age of 30 say discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against nonwhites, while six in ten (60%) white seniors agree.

Among whites in these regions, there are significant age differences in how widely reverse discrimination is perceived as a problem. Only 41% of white residents under the age of 30 say discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against nonwhites, while six in ten (60%) white seniors agree.

Education also matters a great deal. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of whites without a college degree say reverse discrimination is a serious problem, compared to half (50%) of whites with a college degree.

Perceptions of Effort and Success

Most Americans reject the idea that inequality between white and black Americans is primarily due to a lack of effort among black Americans to improve their condition. A majority (55%) of Americans disagree with the statement that “if blacks would only try harder, they would be just as well off as whites.” However, a significant minority (43%) agree.

A majority of every racial and ethnic group rejects the notion that effort is the driving force behind racial inequality. A majority of black (68%), Hispanic (57%), and white Americans (53%) disagree that blacks could be as well off as whites if they only put forth more effort. However, more than two-thirds (68%) of low-affinity whites say blacks would be as well off as whites if they would try harder; only 26% of high-affinity whites agree.

There are yawning political differences on this question. Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to agree that inequality is caused by a lack of effort among black Americans (60% vs. 30%, respectively). The views of independents mirror the general public.

The Southeast and Southwest

Southeast and Southwest residents are more divided on this issue. Close to half (47%) of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions agree that racial inequality is primarily the result of lack of effort among black Americans. A slim majority (51%) disagree.

A majority (52%) of white residents in these regions agree that if blacks would only try harder they would be just as well off as whites. More than four in ten (44%) Hispanics, and more than one-third (37%) of black Americans agree with this statement as well. Low-affinity whites in these regions are more than twice as likely as high-affinity whites to say inequality is due to lack of effort among blacks (67% vs. 33%, respectively).

Among white Americans, gaps across educational lines are evident in these regions, although they are smaller than they are nationwide. A majority (55%) of whites without a college degree believe that gaps between blacks and whites are due to effort, a view shared by 42% of college-educated whites.

There is a wide disparity in the views of Republicans and Democrats in the region. Republicans are roughly twice as likely as Democrats to think that blacks would be more equal if they only tried harder: 65% vs. 33%, respectively.

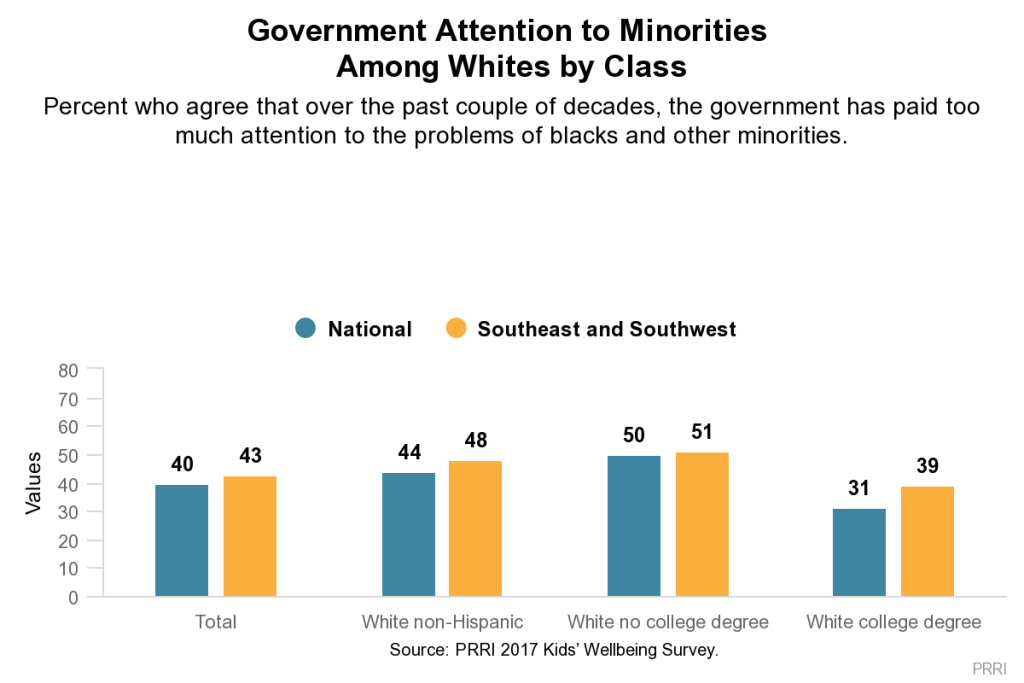

Government Attention to the Problems of Minorities

Most Americans do not believe the government has paid too much attention to the problems of blacks and other minorities over the past couple of decades. A majority (58%) of the public reject this statement, while four in ten (40%) embrace it.

A majority of black (68%), Hispanic (60%), and white Americans (54%) disagree the government has been too focused on the problems confronting blacks and other minorities over the past several decades. More than four in ten (44%) white Americans agree the government has paid too much attention to minority groups in the recent past, while fewer Hispanics (37%) and blacks (28%) agree. Among whites there are divisions by education and affinity. Half (50%) of whites without a college degree agree that government has prioritized too highly the problems of racial and ethnic minorities, compared to 31% of college-educated whites. Low-affinity whites are also much more likely than those with a high affinity to say that the government has paid too much attention to the issue facing black Americans (64% vs. 26%, respectively).

As with other racial attitudes, views about government assistance to minorities are sharply polarized by political affiliation. Nearly six in ten (59%) Republicans believe the government has focused too much attention on the problems of blacks and other minorities, a view shared by only 27% of Democrats. Independents largely mirror the general public.

As with other racial attitudes, views about government assistance to minorities are sharply polarized by political affiliation. Nearly six in ten (59%) Republicans believe the government has focused too much attention on the problems of blacks and other minorities, a view shared by only 27% of Democrats. Independents largely mirror the general public.

The Southeast and Southwest

Most (55%) residents in the Southeast and Southwest regions also reject the notion that the government has paid too much attention to the challenges facing blacks and other minorities. However, more than four in ten (43%) agree.

Opinions on whether the government pays too much attention to the problems of racial minorities vary by race and ethnicity. Roughly half (48%) of white residents in these regions agree the government pays too much attention to the problems of racial minorities, while 40% of Hispanics residents and 30% of black residents report the same.

Among whites in these regions, attitudes vary by educational attainment. A slim majority (51%) of whites without a college degree agree with this statement, compared to 39% of those with a college degree.

Police Treatment of Black Americans and Minority Groups

A majority (57%) of Americans do not believe that police treat black Americans and members of other minority communities generally the same as whites. Roughly four in ten (42%) Americans believe police treat these groups equally. Opinions on whether police officers generally treat blacks and minorities the same as whites vary dramatically by race, ethnicity, and party affiliation.

White Americans are about evenly divided over whether the police treat minority communities the same as whites: 49% agree vs. 51% disagree. More than eight in ten (83%) black Americans and nearly two-thirds (65%) of Hispanic Americans do not believe blacks and other minorities are treated the same by police as whites. Whites without a college degree are only slightly more likely than those with a four-year degree to believe police officers are equitable in their treatment of minority communities (50% vs. 44%, respectively). In contrast, whites with a low affinity for racial, ethnic, and religious minorities are much more likely than high-affinity whites to say the same (61% vs. 36%, respectively).

Though racial differences in views of policing are large, they are dwarfed by differences across political lines. Nearly two-thirds (66%) of Republicans say whites and minorities are treated the same by police, while only 42% of independents and 26% of Democrats say the same. Differences across presidential vote choice are even larger. Roughly seven in ten (71%) Trump supporters think police treat people of all races equally, compared to only fewer than one-quarter (23%) of Clinton supporters.

The Southeast and Southwest

Views about police treatment of minority groups are similar among residents in the Southeast and Southwest. A majority (55%) of the region’s residents do not believe that black Americans and other minority groups receive equal treatment by the police, while 44% agree that they do.

Racial gaps in views on policing are even larger in the Southeast and Southwest than they are elsewhere. A majority (52%) of white residents believe police generally treat people of all races equally, compared to only 16% of black residents. Fewer than four in ten (37%) Hispanics believe police treatment is equitable. Interestingly, there is a smaller gap among whites in these regions by social affinity—fewer than six in ten (58%) whites with low affinity say police officers treat all people equally compared to 42% of those with a high affinity.

As is the case nationally, Republicans and Democrats within these regions hold dramatically different views on the issue of policing equality. More than two-thirds (68%) of Republicans, but only 24% of Democrats in these regions, feel police treat people of all races the same.

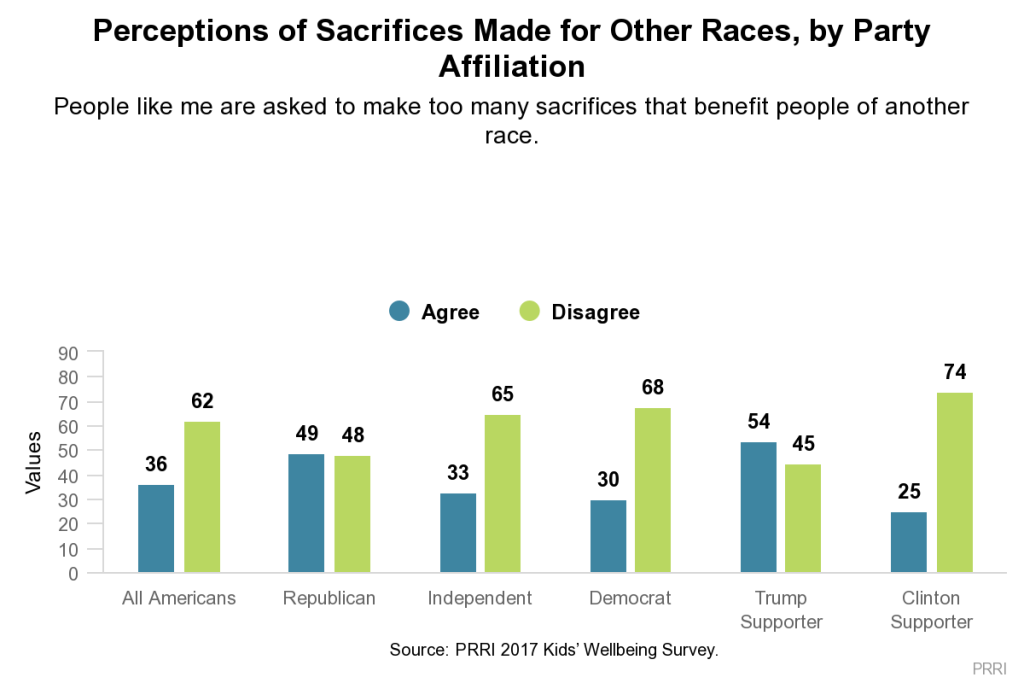

Making Sacrifices to Benefit Other Racial Groups

Americans generally doubt they are required to make sacrifices that benefit other racial and ethnic groups. More than six in ten (62%) Americans do not believe they are being asked to make too many sacrifices to benefit people of another race, while 36% agree.

Interestingly, responses to this question vary little by racial or ethnic identity. Notably, black Americans (42%) are more likely than white (36%) and Hispanic Americans (31%) to agree with this statement.

Political affiliation matters a great deal on this issue. Nearly half (49%) of Republicans and a majority (54%) of Trump supporters feel they are being asked to make too many sacrifices that benefit people of other races. No more than one-third of independents (33%), Democrats (30%), and Clinton supporters (25%) believe they are being asked to make too many sacrifices.

Political affiliation matters a great deal on this issue. Nearly half (49%) of Republicans and a majority (54%) of Trump supporters feel they are being asked to make too many sacrifices that benefit people of other races. No more than one-third of independents (33%), Democrats (30%), and Clinton supporters (25%) believe they are being asked to make too many sacrifices.

The Southeast and Southwest

Whites in the Southeast and Southwest regions are more likely than whites nationally to say they have been asked to make too many sacrifices for people of different races. More than four in ten (42%) whites in these regions agree they have been asked to make too many sacrifices, compared to roughly one-third of black (35%) and Hispanic residents (32%).

Among whites in the Southeast and Southwest, there are notable differences by education level. Whites without a college degree (45%) are more likely than whites with a degree (32%) to say they have been asked to make too many sacrifices for people of another race. White men (45%) are also somewhat more likely than white women (38%) to say they have been asked to make too many sacrifices.

Partisan differences are considerable in these regions. Republicans (49%) are substantially more likely than independents (37%) and Democrats (34%) to say they are having to make too many concessions.

V. Views of Government

Is Government Wasteful?

Americans are generally skeptical of the government’s ability to efficiently and effectively deliver services to citizens. More than six in ten (63%) Americans agree things run by the government are usually inefficient and wasteful. Only 36% of the public disagree.

Views about the efficiency of government vary by race and ethnicity, although majorities of every major group perceive its inefficiency. Approximately two-thirds (66%) of white Americans say the government is usually inefficient and wasteful, compared to 56% of black Americans and 53% of Hispanic Americans.

There are strong partisan differences in perceptions of government’s efficiency. Republicans (74%) and independents (67%) are more likely than Democrats (51%) to agree the government is inefficient and wasteful. It’s notable that even among Democrats, fewer than half (47%) disagree with the statement.

Americans are also not generally inclined to give government the benefit of the doubt. Fewer than half (46%) of the public say the government generally does a better job than it is given credit for, while 53% believe that it does not.

There are no racial or ethnic differences on this issue. Fewer than half of Hispanic (47%), white (45%), and black Americans (44%) say the government does not receive the credit it deserves.

The Southeast and Southwest

Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest U.S. closely resemble the rest of the country on attitudes toward the government. Close to two-thirds (64%) say programs run by the government are usually inefficient and wasteful and fewer than half (45%) say government deserves more credit for the job it does than it gets.

The racial divide is somewhat larger in these regions than it is nationally. Seven in ten (70%) white Americans in these regions agree the government is usually wasteful, a view shared by fewer Hispanic (54%) and black Americans (51%). White residents (41%) are also less likely than black (50%) and Hispanic residents (51%) to say that government does a better job than it gets credit for.

Among residents of the regions, differences in attitudes toward government are stark across lines of party affiliation. Three-quarters (75%) of Republicans say the government is inefficient and wasteful while slightly more than half (52%) of Democrats agree. Importantly, Democrats are only somewhat more likely than Republicans to say the government often does a better job than it gets credit for—52% vs. 40%, respectively.

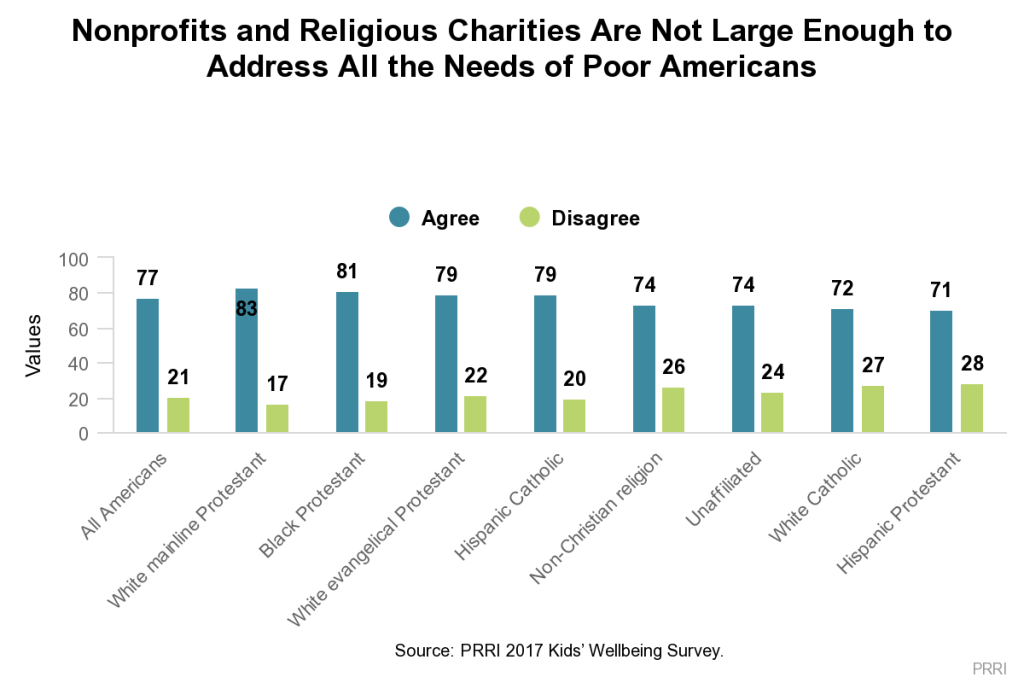

Is Private Charity Enough?

Despite generally negative views about how the government operates, Americans of all types still see a role for government in helping the poor. Only 36% agree the government is providing too many social services that should be left to religious groups and private charities. More than six in ten (62%) disagree. In addition, more than three-quarters (77%) of the public agree nonprofit and religious groups are not large enough to address the needs of poor Americans.

There are modest differences by race and ethnicity in views about the government’s role in the administration of social services. White Americans (39%) are somewhat more likely than Hispanic (29%) and black Americans (28%) to say the government is doing more than it should in this area. But roughly equal numbers of whites (78%), blacks (78%), and Hispanics (74%) agree secular and religious nonprofits do not have the capacity to address the needs of poor Americans.

Republicans and Democrats are sharply at odds in views about the role the government should play in providing social welfare. More than six in ten (61%) Republicans agree the government is doing more than it should, while only 19% of Democrats agree. The views of political independents closely track those of the general public.

There is greater cross-partisan consensus about the inability of nonprofits and religious charities to address the needs of poor Americans. High majorities of Democrats (81%), independents (78%), and Republicans (71%) agree religious and secular charities are not large enough to meet the needs of those living in poverty.

Across different religious denominations and traditions, there is widespread agreement that religious charities and nonprofits are not able to sufficiently address poverty. Roughly eight in ten white mainline Protestants (83%), black Protestants (81%), and white evangelical Protestants (79%), along with roughly three-quarters (76%) of Catholics, agree nonprofits and charities cannot adequately address the needs of poor Americans. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans also agree.

The Southeast and Southwest

Americans living in the Southeast and Southeast express similar views about government’s role in society. About four in ten (42%) Americans living in these regions say government is doing too much, while a majority (57%) disagree.

In the Southeast and Southwest regions, white Americans are more likely to perceive the government as being too involved in the provision of social services. Nearly half (48%) of whites in these regions say government is doing too much, compared to 38% of Hispanics and 29% of black residents. However, there are no significant differences across racial lines in the belief that nonprofit charities are large enough to address the needs of the poor. Roughly three-quarters of black (76%), white (74%), and Hispanic residents (74%) say such organizations are not large enough to address all the needs of poor Americans.

The opinion gap between Republicans and Democrats in these regions is roughly the same as it is nationally. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Republicans in the Southeast and Southwest regions say the government has been too involved in providing social services, a view shared by only one-quarter (25%) of Democrats. There is a political consensus about the inability of nonprofits and religious charities to address all the needs of poor Americans, with at least two-thirds Democrats (81%), independents (73%), and Republicans (69%) expressing agreement.

Does Government Help the People it is Designed to Help?

Two-thirds (67%) of the public agree the government is too often helping the wrong people, while roughly one-third (32%) of the public disagree.

Notably, there is little divergence in opinion across racial and ethnic lines. About two-thirds of Hispanic (65%), white (66%), and black Americans (70%) agree the government too often helps the wrong people.

There are important differences by political affiliation on the issue. More than three-quarters (77%) of Republicans say the government often helps the wrong people, compared to 64% of independents and 61% of Democrats.

The Southeast/Southwest

Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions are similarly inclined to believe the government is helping people it should not. Close to seven in ten (68%) residents in those regions say government too often helps the wrong people.

Views are similar across racial and ethnic lines: Roughly two-thirds of white (69%), black (66%), and Hispanic residents (65%) agree the government is assisting people it should not.

Among white residents, those without a college degree are more likely than those with one to think the government helps the wrong people. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of whites without a college degree say the government too often helps the wrong people, compared to about six in ten (61%) whites with college degrees who say the same.

Among residents in the Southeast and Southwest, there are meaningful differences across party lines, although majorities across the political spectrum agree the government too often helps the wrong people. Republicans (76%) are more likely than independents (68%) or Democrats (61%) to say the government often helps the wrong people.

Views of Government Aid Recipients

Americans are roughly evenly divided on whether people who receive welfare payments from the government are genuinely in need of aid (53%) or taking advantage of the system (45%).

White Americans are even more closely divided over the issue than Americans overall. Half (50%) of white Americans say people receiving welfare need the assistance, while roughly as many (48%) say they are taking advantage of the system. Six in ten black (60%) and Hispanic Americans (60%) say people who receive welfare are genuinely in need of help.

Views of welfare recipients differ drastically by political affiliation. Only 32% of Republicans believe welfare recipients are genuinely in need of help, while a majority of independents (53%) and Democrats (69%) say that they are.

The Southeast/Southwest

Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest are similarly divided in their view of welfare recipients. Nearly half (49%) of residents in these regions say welfare recipients are genuinely in need of assistance, while roughly as many (48%) say they are abusing the system.

White Americans in the Southeast and Southwest regions have considerably more negative attitudes than whites overall toward recipients of welfare. A majority (55%) of whites in these regions say welfare recipients are abusing the system, while 42% say they are in need of help. A majority (55%) of Hispanics and nearly two-thirds (65%) of black Americans say people who receive welfare are truly in need of such assistance.

The views of whites are stratified by educational attainment. Whites without a college degree are much less likely than those with a college degree to say welfare recipients are genuinely in need of help (38% vs. 53%, respectively).

The political gulf in views of welfare recipients eclipses racial and ethnic differences. Democrats are more than twice as likely as Republicans to say welfare recipients are genuinely in need of the assistance (67% vs. 30%, respectively). Independents are closely divided in their views of recipients of welfare.

Trust in Government

Trust in the U.S. government has been stagnant or declining for several decades, and clear majorities of Americans do not trust the federal government to do what is right. Opinions are somewhat more positive, though, when it comes to trust in state and local governments.

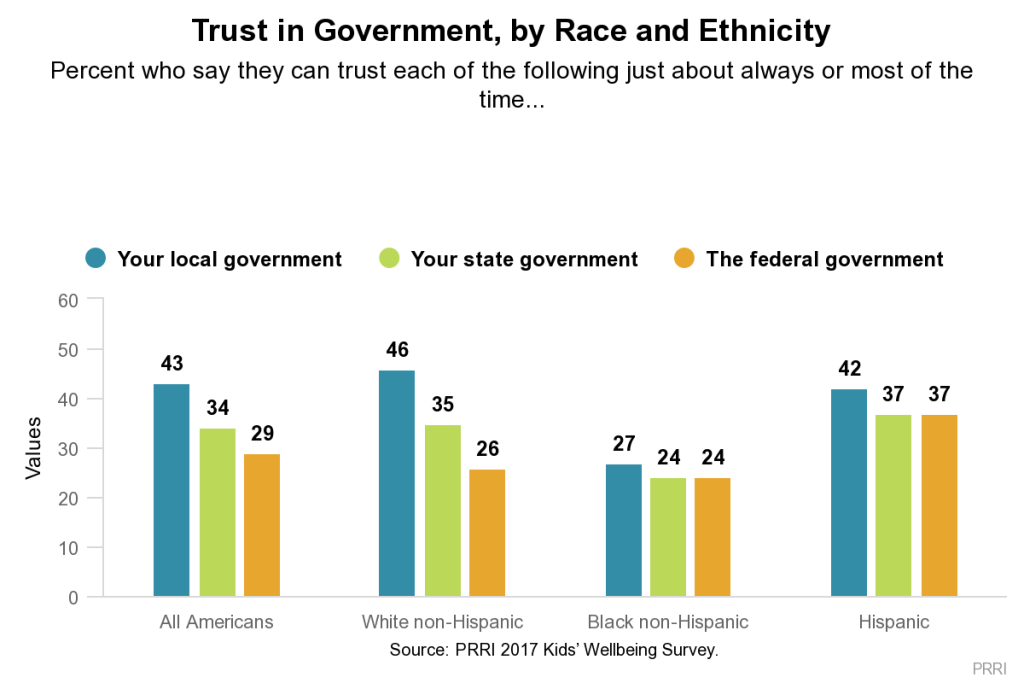

Less than three in ten (29%) Americans say they trust the federal government to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time.” A majority (56%) say it can be trusted “only some of the time,” and 15% say it can be trusted “none of the time.”

Americans exhibit only slightly more confidence in their state governments. Roughly one-third (34%) say they trust their state government most of the time or nearly always. About half (51%) say they trust their state government some of the time, while 14% say they never trust it. More than four in ten (43%) Americans say they trust their local government most of the time or nearly always. Roughly as many (45%) say their local government can be trusted some of the time, and 10% say they never trust it.

Trust in government does vary markedly across racial lines—especially for lower levels of government. Black and white Americans are roughly equally distrusting of the federal government: Only 26% of whites and 24% of blacks say they trust the federal government always or most of the time. More than one-third (37%) of Hispanics report trusting the federal government at least most of the time. In contrast, Hispanic and white Americans are more likely than black Americans to express trust in their state government (37% vs. 35% vs. 24%, respectively). Similarly, while more than four in ten (42%) Hispanics and close to half of white Americans (46%) trust their local government at least most of the time, only 27% of black Americans feel similarly.

The Southeast/Southwest

The Southeast/Southwest

Americans in the Southeast and Southwest regions report similar levels of trust in federal (30%), state (36%), and local governments (42%).

Disparate levels of trust exist in the Southeast and Southwest among racial and ethnic groups. Hispanic residents of these regions (38%) are the most likely to have high levels of trust in the federal government, while trust in the federal government is roughly equal among black (29%) and white residents (27%) of these regions. When it comes to state governments, however, Hispanics (41%) and whites (36%) in these regions are considerably more trusting than black residents (27%). The trust gap is even larger on the local level, with more than four in ten Hispanics (46%) and whites (43%) expressing trust in their local government, compared to fewer than three in ten (28%) black residents.

Notably, partisan differences in trust are relatively modest. More than three in ten Republicans (37%) and Democrats (31%) say they can trust the federal government at least most of the time. Far fewer independents (23%) feel the same. The trust gap grows significantly larger in views about state and local government. Half (50%) of Republicans—compared to fewer than one-third of independents (31%) and Democrats (31%)—say they trust their state government at least most of the time. Similarly, while a majority (55%) of Republicans say they trust their local government at least most of the time, only 34% of independents and 39% of Democrats report similar levels of trust.

VI. Issue Priorities and Community Problems

Critical Issues in the Country

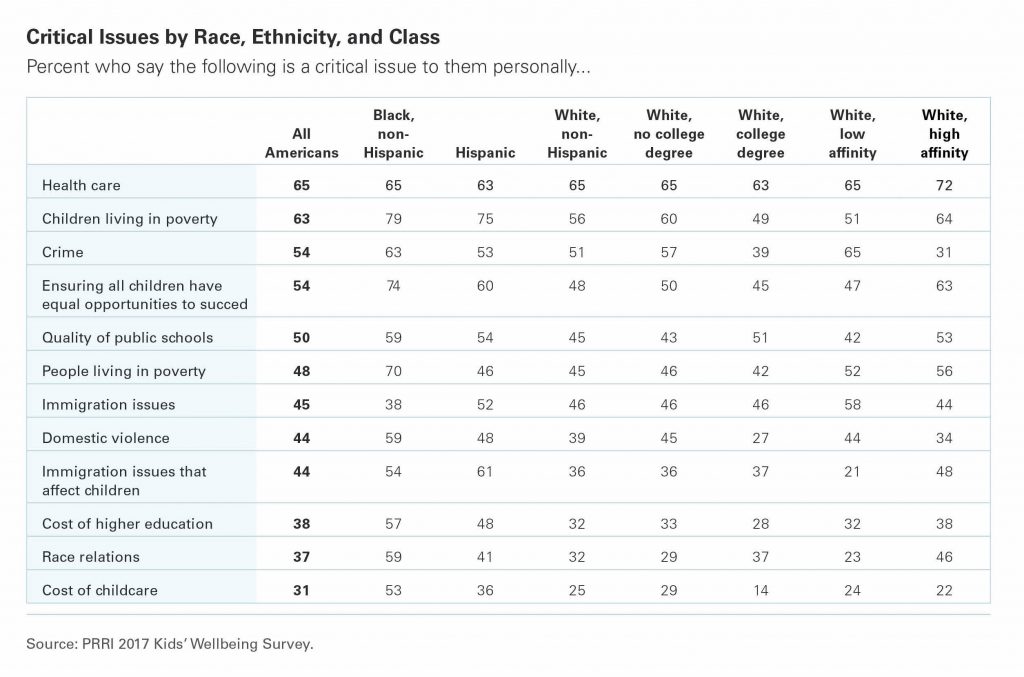

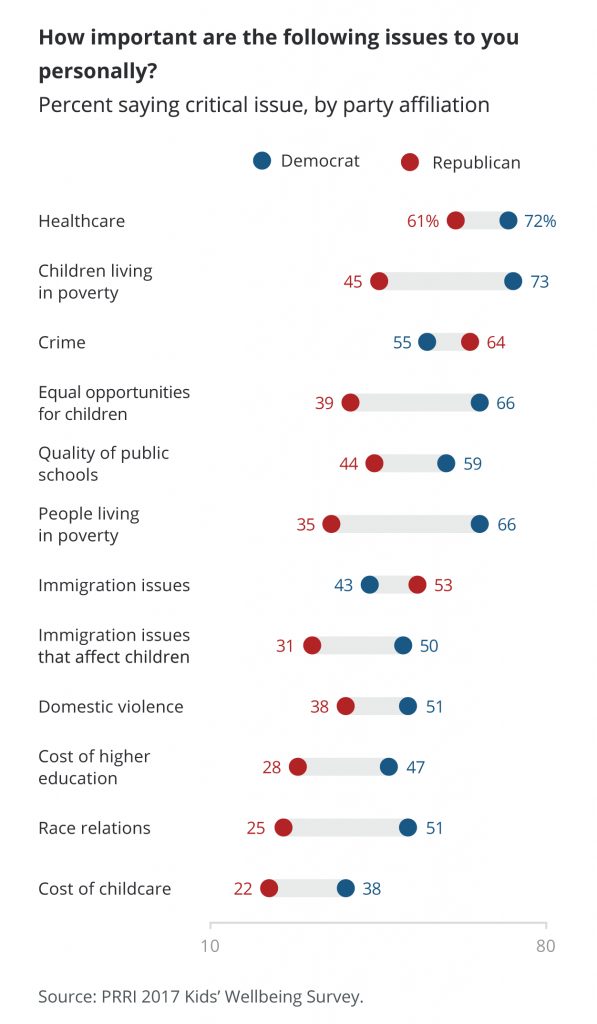

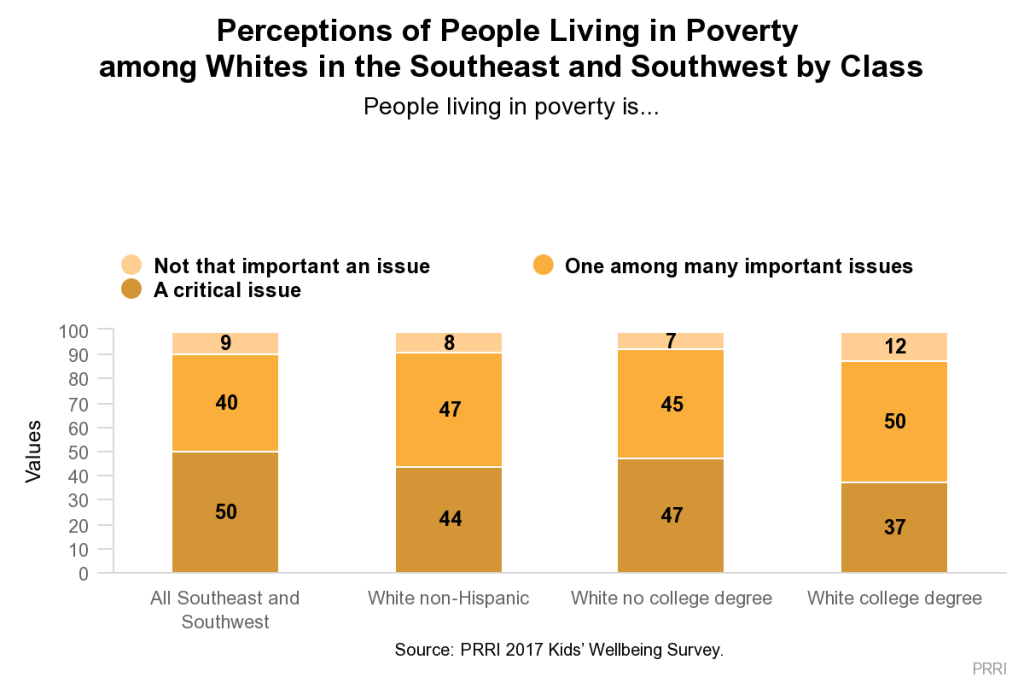

No issues are viewed as more critical among Americans today than health care and child poverty. Nearly two-thirds (65%) of Americans say health care is a critical issue to them, and nearly as many (63%) cite child poverty as a critical issue. Notably, fewer than half (48%) of Americans say the issue of poverty generally is a critical issue. At least half the public say crime (54%), ensuring all children have equal opportunities to succeed (54%), and the quality of public schools (50%) are critically important issues. Fewer than half of Americans cite immigration (45%) or immigration issues that affect children (44%), domestic violence (44%), the cost of higher education (38%), race relations (37%), or the cost of child care (31%) as critical issues to them.

The importance of particular issues varies by race and ethnicity. At least three-quarters of black (79%) and Hispanic Americans (75%) say that child poverty is a critical concern, a view shared by just 56% of white Americans. However, the views of white Americans vary considerably by education and social affinity. Six in ten (60%) white Americans without a four-year college degree say the issue of child poverty is critically important, compared to fewer than half (49%) of whites with a college degree. Whites with a high affinity for minority groups are more likely than low-affinity whites to prioritize child poverty (64% vs. 51%, respectively).

Americans overall are about equally as likely to prioritize immigration generally and immigration issues affecting children. White Americans, however, are more likely to say immigration is a critical concern than they are to say immigration issues that impact children are a critical concern (46% vs. 36%, respectively). In contrast, black and Hispanic Americans are more likely to prioritize immigration issues that affect children than they are to prioritize immigration generally: More than six in ten (61%) Hispanic Americans and a majority (54%) of black Americans say immigration issues that impact children are a critical priority, while only about half (52%) of Hispanics and fewer than four in ten (38%) black Americans say immigration is a critical issue. There are no educational differences among whites in concerns about immigration issues that affect children, but whites with a high affinity are more likely than those with a low affinity to say this issue is a priority (48% vs. 21%, respectively).

Black and Hispanic Americans also report being more concerned about providing equal opportunities for children. Approximately three-quarters (74%) of black Americans and six in ten (60%) Hispanic Americans say that ensuring all children have equal opportunities to succeed is critical. In contrast, fewer than half (48%) of white Americans say this is a critical issue for them. There are no differences among whites by education, but low-affinity whites are much less likely to say this is a critical issue than high-affinity whites (47% vs. 63%, respectively).

Black Americans are more likely than white or Hispanic Americans to rate a number of other issues as critically important. A majority (53%) of black Americans say the cost of childcare is critically important to them, compared to only 36% of Hispanics and 25% of whites. Similarly, nearly six in ten (59%) black Americans say domestic violence is a major concern, while fewer than half of Hispanic (48%) and white Americans (39%) agree. However, whites without a college degree are much more likely than white college graduates to cite domestic violence as a critical issue (45% vs. 27%, respectively).

In general, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to prioritize issues affecting children, particularly vulnerable children. Nearly six in ten (59%) Democrats compared to fewer than half of independents (45%) and Republicans (44%) say the quality of public schools is a critical issue to them personally. About two-thirds (66%) of Democrats and a majority (55%) of independents say that ensuring equal opportunities for children is a critical concern, while only 39% of Republicans say the same. Child poverty is a critical issue for nearly three-quarters of Democrats (73%) and more than six in ten (61%) independents. Fewer than half (45%) of Republicans say children living in poverty is a critical issue. Notably, while Republicans are somewhat more likely than Democrats to prioritize immigration in general (53% vs. 43%, respectively), Democrats express greater concern about immigration issues that impact children (50% vs. 31%, respectively).

The Southeast and Southwest

In the Southeast and Southwest regions, no issues are ranked as more important among residents than health care (65%) and children living in poverty (62%). There are notable racial and ethnic divisions on these issues. More than seven in ten black (79%) and Hispanic residents (72%) of these regions say children living in poverty is a critical issue to them. Substantially fewer (55%) white residents of these regions agree.

A majority (55%) of residents in these regions say that ensuring equal opportunity for children is a critical priority, although racial and ethnic differences are manifest: Three-quarters (75%) of black residents, roughly six in ten (59%) Hispanic residents, and fewer than half (48%) of white residents identify this issue as critical. Notably, white residents with a college degree are much more likely to prioritize child poverty (57%) than ensuring equal opportunities for all children (43%). In contrast, white residents without a college degree are about as likely to say child poverty and providing equal opportunities for children are critical concerns (55% vs. 50%, respectively).

Concerns about poverty expressed by white residents vary sharply by education level and gender. Whites without a college degree express substantially greater concern about poverty than those with a college education (47% vs. 37%, respectively). A majority (54%) of white women but only about one-third (34%) of white men say people living in poverty is a critical issue.

Problems in American Communities

Problems in American Communities

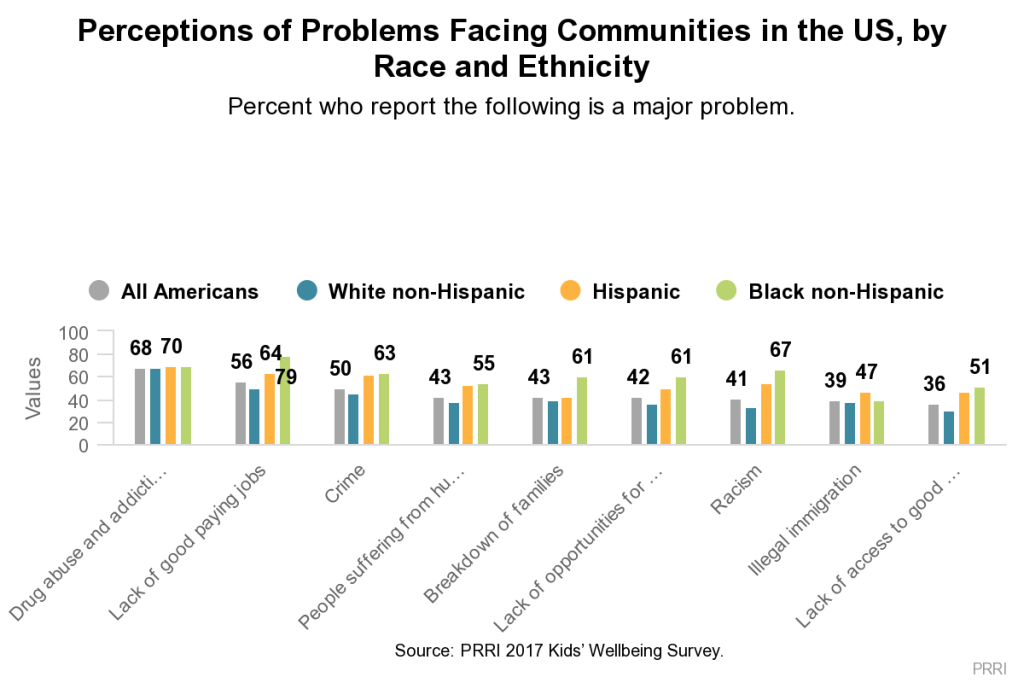

No issue is cited by more Americans as a major problem for U.S. communities than drug abuse and addiction. More than two-thirds (68%) of Americans say drug abuse and addiction is a major problem in U.S. communities. A majority (56%) of the public cite the lack of good paying jobs as a major problem, while half (50%) report crime is a major concern. Fewer than half of Americans say people suffering from hunger and malnutrition (43%), the breakdown of families (43%), a lack of opportunities for young people (42%), racism (41%), illegal immigration (39%), and a lack of access to good public schools (36%) are major problems in communities around the country.

White Americans express far less concern than black and Hispanic Americans about many of these issues. One-third (33%) of whites say racism is a major problem, compared to a majority (54%) of Hispanic Americans and two-thirds (67%) of black Americans. A similar number (30%) of white Americans say lack of access to good public schools is a major problem, while roughly half of Hispanic (47%) and black Americans (51%) say this is a major issue. White Americans report substantially less concern about a lack of opportunities for young people in U.S. communities—only 36% say it’s a major problem, while half (50%) of Hispanic Americans and more than six in ten (61%) black Americans say it’s a pressing issue. White Americans (46%) are also less likely than Hispanic (62%) and black Americans (63%) to report crime is a serious problem afflicting communities in the U.S. Roughly equal numbers of black (55%) and Hispanic Americans (53%) cite hunger and malnutrition as major community problems, while fewer (38%) white Americans agree. Black Americans are unique to the extent that they identify the “breakdown of families” as a problem for U.S. communities. More than six in ten (61%) black Americans say this is a substantial problem, compared to 43% of Hispanics and 40% of whites. Notably, consensus among racial and ethnic groups emerges on the issue of drug abuse. About seven in ten white (68%), black (70%), and Hispanic Americans (70%) say drug abuse and addiction are serious problems facing communities.

The Southeast and Southwest

The Southeast and Southwest

Americans who live in the Southeast and Southwest regions express similar concerns about the problems facing communities in the U.S. Two-thirds (67%) of residents in these regions say drug addiction and abuse is a major problem afflicting communities, while nearly six in ten (58%) say a lack of good paying jobs is a major problem. Similar numbers of black (71%), white (67%), and Hispanic residents (63%) cite drug abuse and addiction as a significant problem, but racial and ethnic divisions are much more pronounced on the issue of jobs. A majority of white (53%) and Hispanic residents (59%), compared to three-quarters (75%) of black residents, say a lack of good paying jobs is a major problem.

Racial divisions in the Southeast and Southwest regions mirror those nationally. About two-thirds (66%) of black Americans say a lack of opportunities for youth is a major problem, compared to half (50%) of Hispanics and 39% of whites. Black Americans (62%) are also much more likely than white (44%) and Hispanic Americans (40%) to say the breakdown of families is a major problem confronting American communities.

VII. Child Welfare Policies

Tax Breaks for Low-Income Parents

Nationally, an overwhelming majority (87%) of Americans support providing tax breaks to low-income parents with child support obligations to help them care for their children, and more than four in ten (41%) Americans strongly support this policy.

Support for tax breaks for low-income parents is strong across the lines of age, race, and gender. The policy enjoys considerable bipartisan support, though support is more pronounced among Democrats and independents. More than three-quarters of Democrats (92%), independents (87%), and Republicans (77%) favor tax breaks for low-income parents. A slim majority (51%) of Democrats strongly favor the policy, compared to 39% of independents, and 28% of Republicans.

There is robust support for such a policy among Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions. More than eight in ten (85%) residents of these regions express support for providing tax breaks to low-income parents with child support obligations. There is broad support for this policy across racial, ethnic, and generational lines.

Pre-K Education

Americans overwhelmingly support free pre-K education: Eight in ten (80%) Americans favor providing free pre-kindergarten services to all children in their state, including 40% who strongly favor this policy.

Support for universal pre-K education stretches across racial and ethnic groups. At least three-quarters of white (77%), Hispanic (87%), and black Americans (88%) favor providing free pre-K education in their state.

The most significant differences in support for free pre-K are observed along partisan lines. While majorities of all political parties support free pre-K, Democrats (92%) express far more staunch support for the policy, followed by Independents (80%) and Republicans (65%).

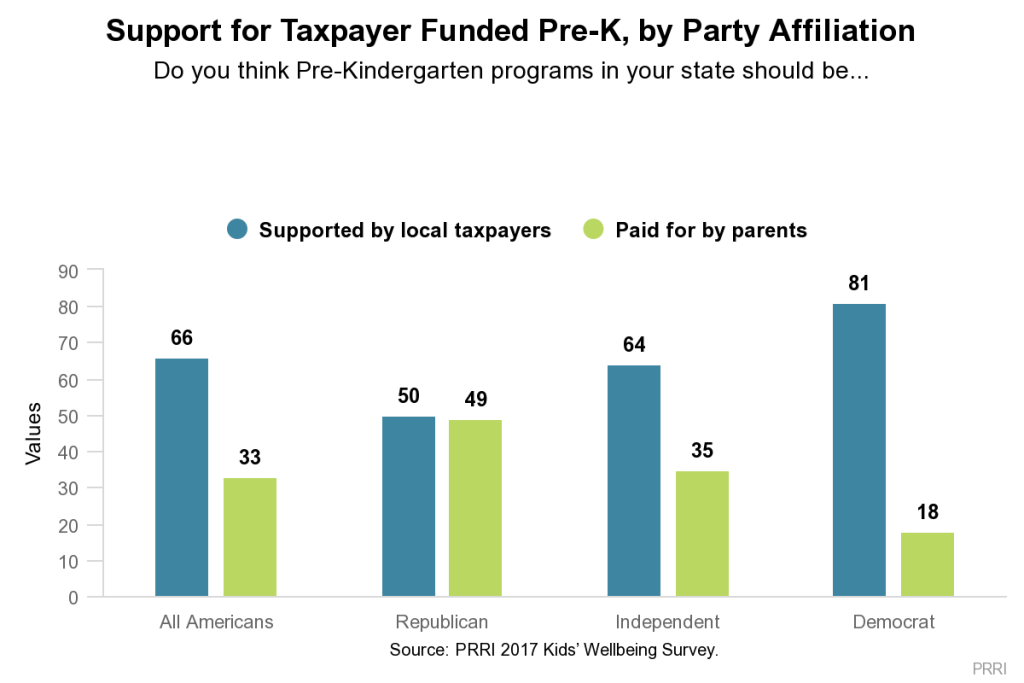

Nearly two-thirds (66%) of Americans say pre-K programs in their state should be supported by local taxpayers the same way public schools are funded; only one-third (33%) say parents should be obligated to pay for such programs for their children themselves.

While majorities of all racial and ethnic groups say taxpayers should fund pre-K, support is strongest among black (83%) and Hispanic Americans (73%) and lowest among whites (61%).

Differences among partisans are considerable. Roughly eight in ten (81%) Democrats and about two-thirds (64%) of independents say local taxpayers should support pre-K programs. Republicans, however, are closely divided: Half (50%) say local taxpayers should support pre-K programs, while 49% say parents should be obligated to pay for such programs for their children themselves.

Differences among partisans are considerable. Roughly eight in ten (81%) Democrats and about two-thirds (64%) of independents say local taxpayers should support pre-K programs. Republicans, however, are closely divided: Half (50%) say local taxpayers should support pre-K programs, while 49% say parents should be obligated to pay for such programs for their children themselves.

Similar degrees of support emerge among Americans residing in the Southeast and Southwest. More than eight in ten (81%) Americans in these regions are in favor of providing free pre-Kindergarten access to all children in their state, compared to 18% who do not support this policy.

Government Support for Extended Family Caregivers

More than eight in ten (84%) Americans agree the government should provide financial assistance to relatives, such as grandparents, who are able to care for children who have been in foster care.

Such a policy sees overwhelming support among Americans of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds. More than eight in ten white (81%), Hispanic (88%), and black Americans (91%) agree the government should support the extended family who care for children.

This policy also garners support across the political spectrum. More than three-quarters of Democrats (93%), independents (80%), and Republicans (78%) agree the government should support the extended family of children who serve as their caregivers.

More than eight in ten (85%) Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions express support for providing financial assistance to relatives who take care of children, compared to 15% who do not support such a policy.

Public School Funding

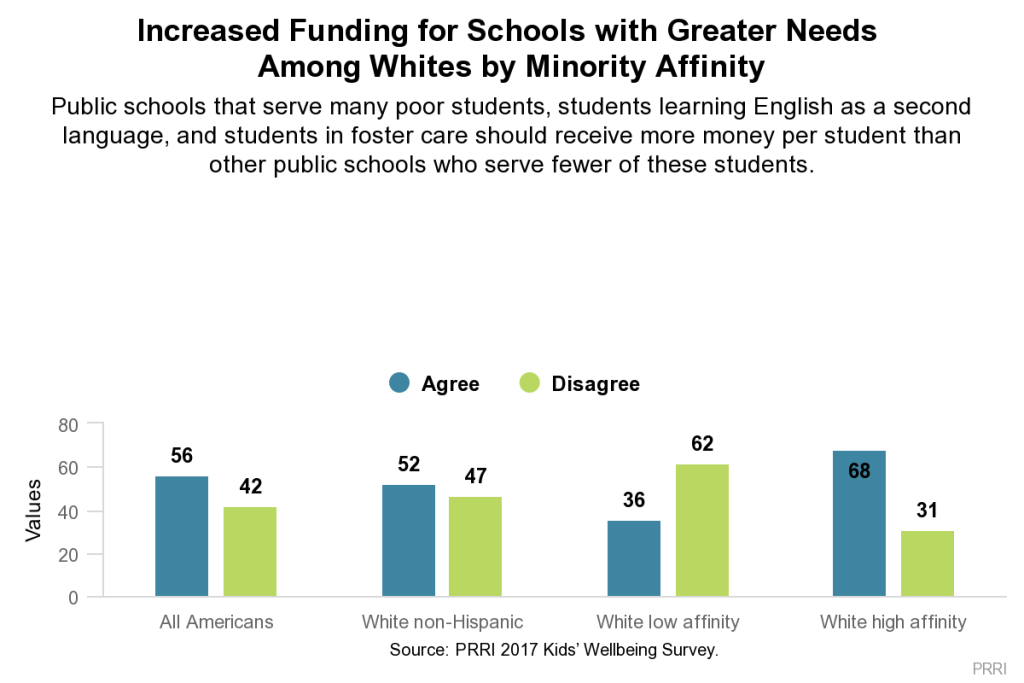

A majority (56%) of Americans agree public schools that serve many poor students, students learning English as a second language, and students in foster care should receive more money per student than public schools who serve fewer of these students. More than four in ten (42%) Americans oppose this policy.

Substantial differences of opinion exist among Americans by racial and ethnic background. More than seven in ten (71%) Hispanic Americans and nearly two-thirds (65%) of black Americans favor a policy that provides extra resources to schools serving students with greater needs, compared to a slim majority (52%) of white Americans. High-affinity whites are far more likely than those with low affinity to support increased aid for these types of public schools (68% vs. 36%, respectively).

Substantial differences of opinion exist among Americans by racial and ethnic background. More than seven in ten (71%) Hispanic Americans and nearly two-thirds (65%) of black Americans favor a policy that provides extra resources to schools serving students with greater needs, compared to a slim majority (52%) of white Americans. High-affinity whites are far more likely than those with low affinity to support increased aid for these types of public schools (68% vs. 36%, respectively).

Stark differences emerge along partisan lines. Seven in ten (70%) Democrats agree schools that serve disadvantaged populations should receive additional funding, while fewer than half (45%) of Republicans agree.

Views on the policy vary considerably by age: More than two-thirds (68%) of young Americans (age 18-29) say schools that serve students with outstanding needs should receive more funding, compared to 52% of seniors (age 65 or older) who agree.

A majority (56%) of Americans living in the Southeast and Southwest regions express support for such a policy. Hispanic residents (69%) of these regions are among the strongest supporters of the policy, while significantly fewer black (56%) and white residents (51%) express support.

Financial Incentives for Foster Care

Most Americans believe financial assistance significantly influences people’s decisions to become foster parents. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of Americans say people often agree to become foster parents because of the financial support they receive from the government.

The belief that financial considerations often influence people’s decisions to take in foster children is about equally as strong among different racial and ethnic groups. At least seven in ten black (79%), white (72%), and Hispanic Americans (72%) agree people often become foster parents because of the money they receive from government. About four in ten (39%) blacks say such deliberation occurs very often, compared to 28% of Hispanics and 24% of whites who say the same.

This view is also largely shared among residents of the Southeast and Southwest regions of the U.S. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Americans residing in these regions say financial incentives often inspire people to become foster parents.

VIII. Criminal Justice Policies

Criminal History

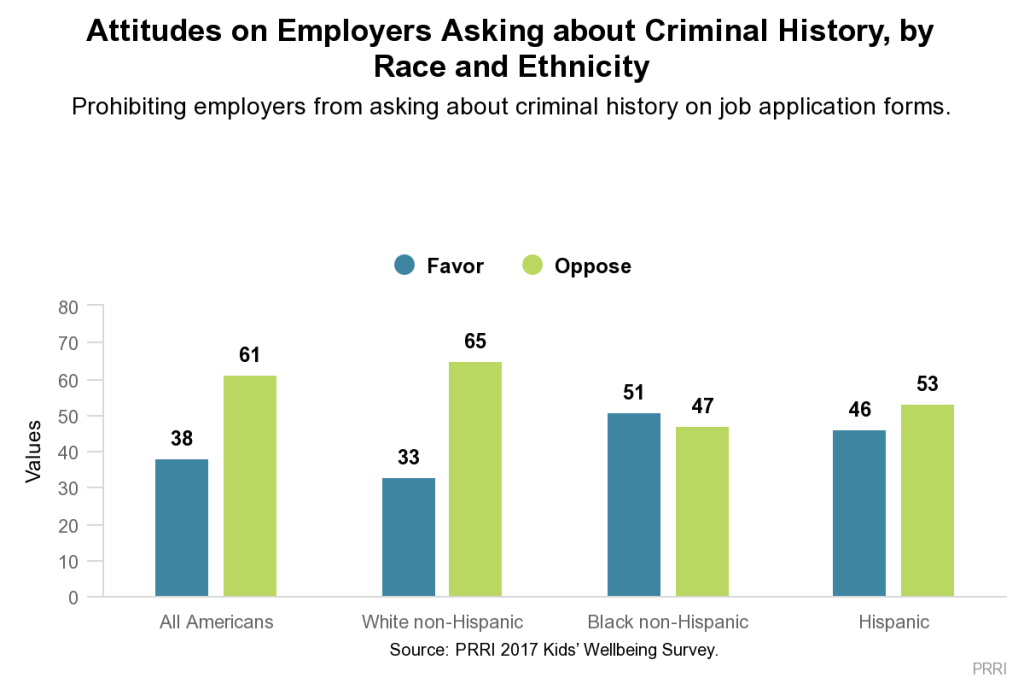

Most Americans believe employers should be able to ask about criminal history on job application forms, and oppose policies that would forbid them from doing so. Only 38% of Americans agree employers should be prohibited from asking about criminal history on job application forms; approximately six in ten (61%) oppose such a policy.

White Americans (65%) are the most likely among racial and ethnic groups to oppose prohibiting employers from asking about criminal history, while Hispanic Americans are more closely divided (53% oppose, 46% favor). Fewer than half (47%) of black Americans oppose such a policy, while a slim majority (51%) favor prohibiting employers from asking about criminal history on job application forms.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Republicans, compared to about six in ten (59%) independents and a majority (53%) of Democrats, say employers should not be restricted from inquiring about criminal history on job application forms.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Republicans, compared to about six in ten (59%) independents and a majority (53%) of Democrats, say employers should not be restricted from inquiring about criminal history on job application forms.

The Southeast and Southwest

Views among residents of the Southeast and Southwest regions are nearly identical to the general public. More than six in ten (62%) Americans in these regions say employers should not be prohibited from asking about criminal history as part of the job application process. More than one-third (37%) of residents support such a policy.

Divisions by race and ethnicity in the Southeast and Southwest in views on this policy are stark. A slim majority (53%) of blacks in these regions support policies that would stop employers from inquiring about criminal history, compared to fewer than half (44%) of Hispanics and only 30% of whites.

Partisanship plays a significant role in explaining attitudes toward this issue. Close to half (47%) of Democrats in the Southeast and Southwest support a policy that would prohibit employers from asking about criminal history, while four in ten (40%) independents and only one in five (20%) Republicans support such a policy. Eight in ten (80%) Republicans, nearly six in ten (59%) independents, and a slim majority (52%) of Democrats in these regions oppose this policy.

Sentencing

More than six in ten (61%) Americans believe judges should always consider the impact on children and families when making sentencing and prison assignment decisions for parents convicted of a crime. Nearly four in ten (38%) say judges should not be required to consider such circumstances when making sentencing decisions.

There are substantial differences of opinion between Americans of varying racial and ethnic backgrounds. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of black Americans and roughly six in ten Hispanic (63%) and white Americans (58%) say judges should consider family circumstances when making sentencing and other judicial decisions.

There is a wide disparity in the views of partisans on the issue. More than seven in ten (72%) Democrats believe judges should consider the impact on children and families when making sentencing and prison assignment decisions, compared to nearly six in ten (59%) independents and roughly half (51%) of Republicans. Nearly as many (48%) Republicans say judges ought not to worry about how sentencing decisions would impact children.

There is greater consensus among the public over whether nonviolent juvenile offenders belong in prison. More than three-quarters (77%) of Americans say judges should find alternatives to prison for nonviolent juvenile offenders.

This view is embraced by wide swathes of the racial and ethnic spectrum. More than three-quarters of Hispanics (76%), whites (77%), and blacks (81%) favor alternatives to prison for nonviolent juvenile offenders.

There is political consensus on the issue: Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Republicans and at least eight in ten independents (80%) and Democrats (83%) say judges should be encouraged to find alternatives to prison for nonviolent juvenile offenders.

The Southeast and Southwest

In general, residents of the Southeast and Southwest regions agree judges should consider the interests of families when handing out sentences to people convicted of crimes. More than six in ten (61%) residents of these regions agree judges should take into account considerations of children and families when making sentencing and prison assignment decisions.

There are similar differences of opinion among residents of these regions by racial and ethnic background. More than seven in ten (72%) blacks and two-thirds (67%) of Hispanics in the Southeast and Southwest say judges should take into account family considerations when making sentencing decisions, while fewer (57%) whites say the same.

Democrats (73%) in the Southeast and Southwest are also more likely than independents (61%) and Republicans (52%) in these regions to believe the considerations of families and children should be taken into account.

Roughly three-quarters (76%) of Southeasterners and Southwesterners favor a policy that would encourage judges to find alternatives to prison for nonviolent juvenile offenders.

Bail and Incarceration for Nonviolent Offenders

Most Americans do not believe it is appropriate for nonviolent offenders who cannot make bail to remain incarcerated. More than six in ten (63%) Americans agree that people convicted of nonviolent crimes should not be held in jail between their arrest and trial date simply because they cannot afford bail; 35% disagree.

There is general consensus on the issue across racial and ethnic lines. Nearly seven in ten (69%) blacks and roughly six in ten whites (62%) and Hispanics (59%) do not believe nonviolent offenders who cannot afford bail should remain imprisoned until their trial.

There are only modest differences across the political divide. More than six in ten Democrats (69%) and independents (63%) say nonviolent offenders who cannot afford bail should not be held in jail between their arrest and trial date, compared to a majority (56%) of Republicans who say the same.

The Southeast and Southwest