Executive Summary

Members of Generation Z are coming into their own politically, socially, and culturally, bringing their values and viewpoints to their communities and workplaces, and to our nation’s political system. In addition to being the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in our nation’s history, Gen Z adults also identify as LGBTQ at much higher rates than older Americans. Like millennials, Gen Zers are also less likely than older generations to affiliate with an established religion.

This report considers what sets members of Generation Z apart from older generations in terms of their political and cultural values, their faith in communities and political institutions, and their views on religion and the importance of diversity and inclusion in the nation’s democracy. The report is based on both the results of a national survey of all Americans, which includes oversamples of Generation Z — both Gen Z adults (ages 18–25) and Gen Z teens (13–17) — and on an analysis of ten virtual focus groups that included a wide cross section of Gen Z adults from across the United States.

Gen Z adults trend slightly less Republican than older Americans. More than half of Gen Z teens do not identify with a major party, but most share their parents’ party affiliation.

- Gen Z adults (21%) are less likely than all generational groups except millennials (21%) to identify as Republican. Meanwhile, 36% of Gen Z adults identify as Democrats, and this rate is similar to other generations, with the exception of Gen Xers, who are less Democratic (31%).

- More than half of Gen Z teens (51%) do not identify with either major political party, compared with 43% of Gen Z adults. Most Gen Z teens share the same partisan identity as their parents.

Gen Z adults are more liberal than older Americans. Gen Z teens are more moderate.

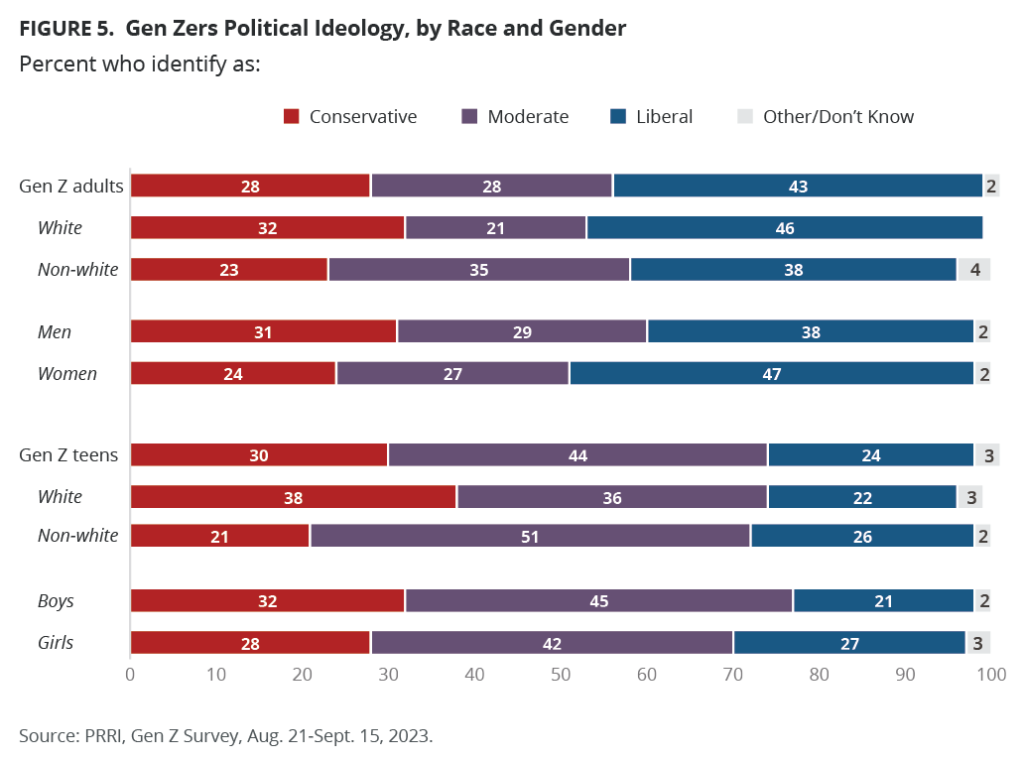

- With the exception of millennials (24%), Gen Z adults (28%) are notably less likely than other generational cohorts to identify as conservative. And Gen Z adults (43%) identify as liberal at a higher rate than other generations. A plurality of Gen Z teens (44%) identify as moderate.

- While Gen Z women are substantially more liberal than Gen Z men (47% vs. 38%), that gender gap is smaller among Gen Z teens, with 27% of teen girls and 21% of teen boys identifying as liberal. By contrast, white teens are more likely to identify as conservative (38%) than non-white teens (21%).

Gen Z is more religiously diverse than older generations. Gen Z teens mirror their parents’ religious affiliation. Gen Z teens are more likely than Gen Z adults to attend church or find religion important.

- Gen Z adults are notably less likely to identify as white Christians and more likely to identify as religiously unaffiliated than older generations, with the exception of millennials.

- More than eight in ten white Christian Gen Z teens (83%) and Christian Gen Z teens of color (85%) report belonging to the same religion as their parents, compared with 68% of religiously unaffiliated teens.

- Gen Z Republicans—both adults and teens—attend church more often, express that religion is more important to them, and have higher trust in organized religion than Gen Z Democrats or independents.

Most Gen Z Americans, particularly Gen Z Democrats, are more likely than older Americans to believe that generational change in political leadership is necessary to solve the country’s problems. Younger and older generations both express a lack of understanding across generational lines.

- While 43% of Americans agree that “We won’t be able to solve the country’s big problems until the older generation no longer holds power,” 58% of Gen Z adults (including 74% of Democrats) and 54% of millennials agree. Less than 4 in 10 Americans (37%) believe the country will be worse off when younger generations hold power.

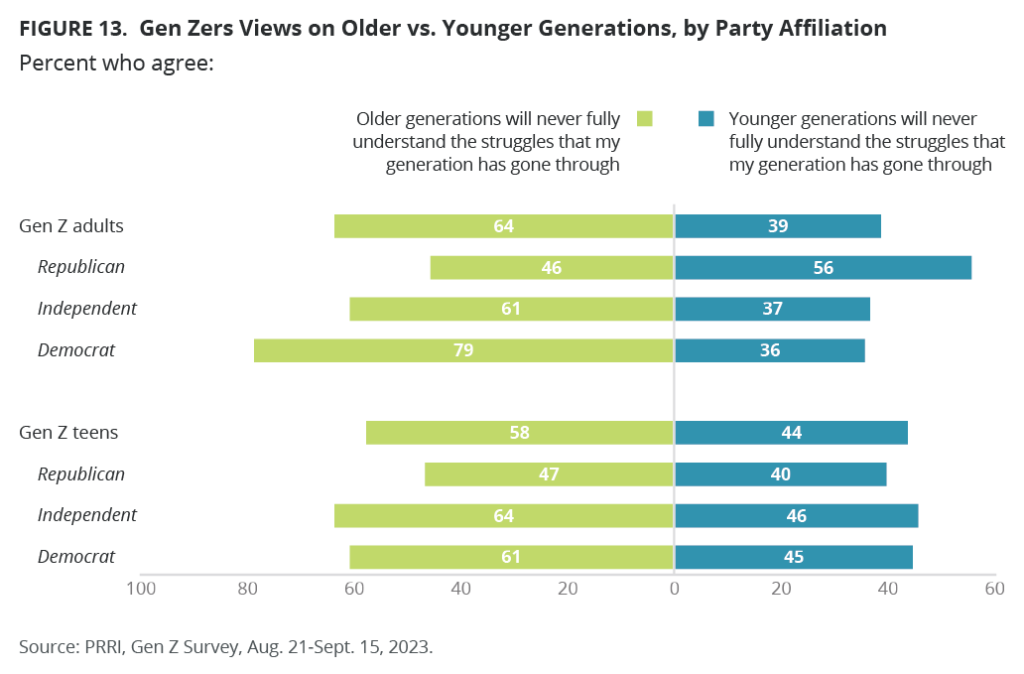

- Majorities of both Gen Z adults (64%) and Millennials (59%) believe that older generations will never fully understand the struggles of younger Americans.

- Strong partisan and gender divides appear among Gen Z adults, with Gen Z Democrats (79%) and women (73%) more likely than Gen Z Republicans (46%) and men (54%) to agree with the idea that older generations will never fully understand their struggles.

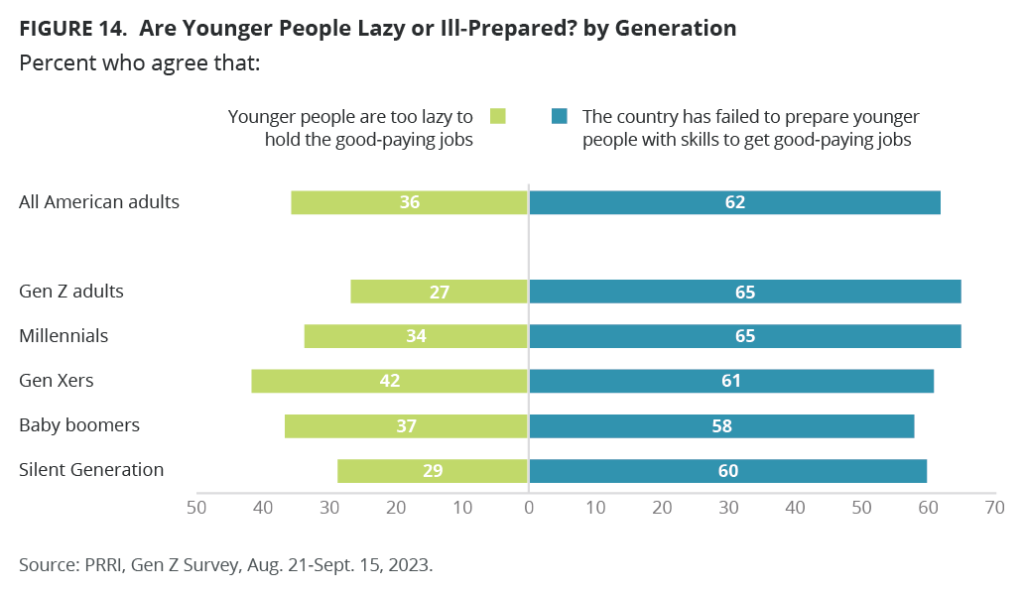

Americans overall largely reject the notion that young people are too lazy to get good jobs, and instead believe that they lack necessary training.

- Just about one-third of Americans (36%) say that younger people are too lazy to hold good-paying jobs. Nearly three in ten Gen Z adults (27%) and members of the Silent Generation (29%) agree with this statement, compared with 34% of Millennials, 37% of baby boomers, and 42% of Gen X.

- More than 6 in 10 Americans (62%) agree that the country has failed to prepare younger people with skills to get good jobs.

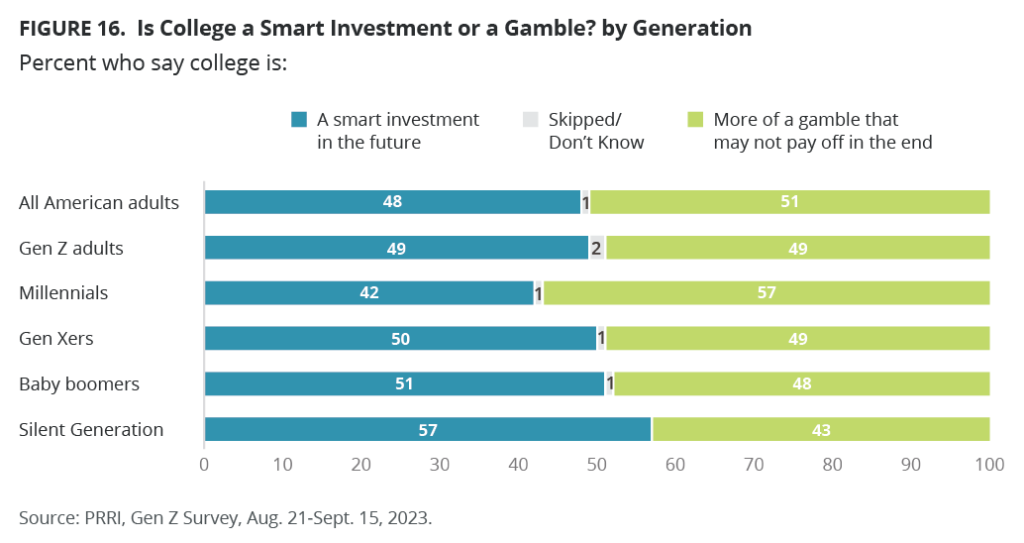

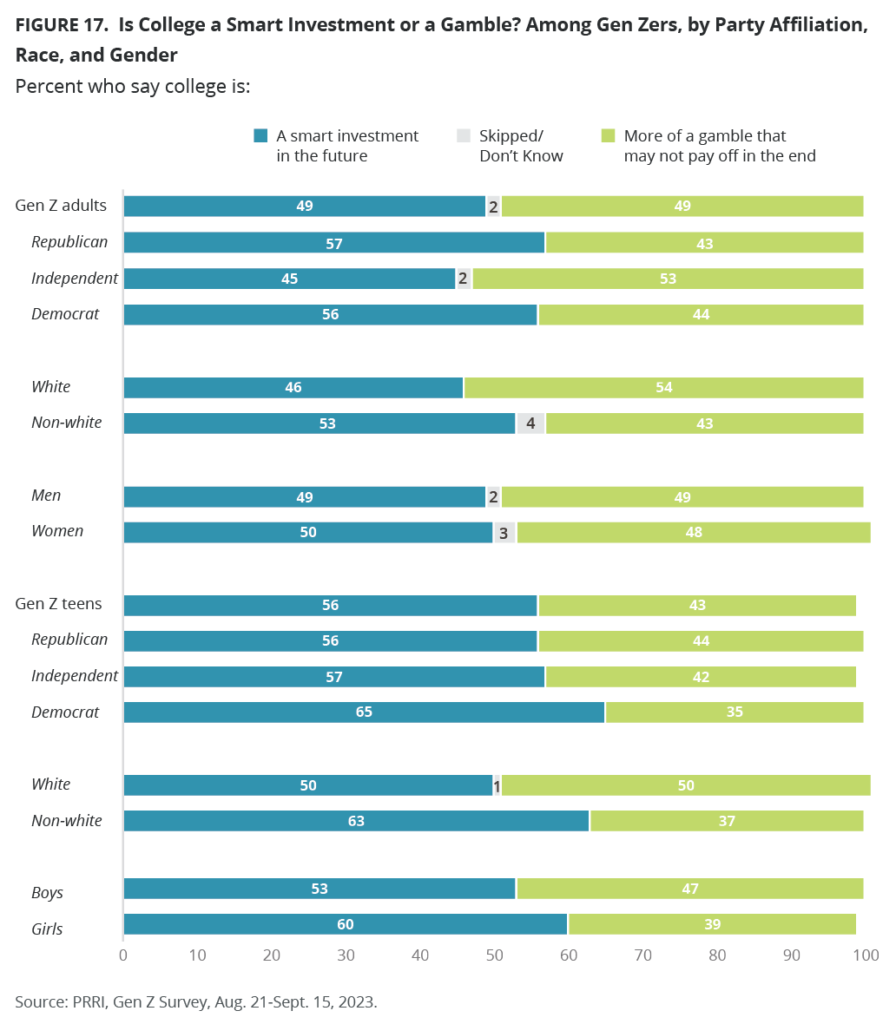

Only half of Gen Z adults think college is a smart investment in the future. Gen Z teens express more optimism about college’s financial impact on their future.

- Half of Gen Z adults (49%) say college is a smart investment, compared with 56% of Gen Z teens. Millennials (42%) are the generation least likely to say that college is a smart investment.

- Majorities of both adult and teen Gen Z partisans and teen Gen Z independents believe college remains a smart investment, while only 45% of adult Gen Z independents hold this view.

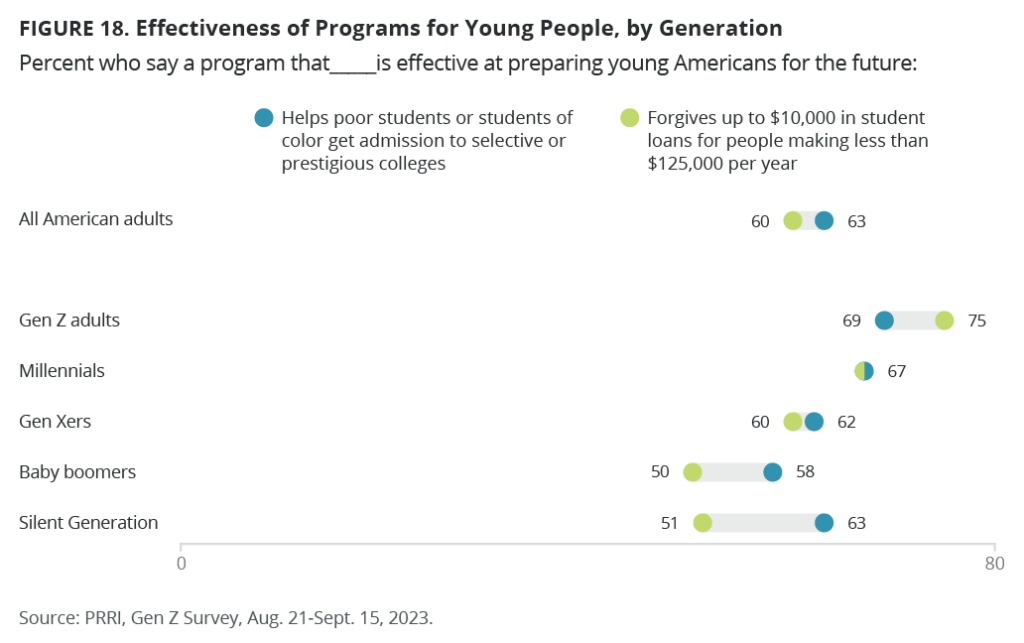

Gen Z adults strongly back affirmative action programs for poor students or students of color, as do most Americans. At least 3 in 4 Gen Z adults support student loan forgiveness, as well as investment in programs to fund technical school, community service, or training to understand the political system.

- Most Americans (63%) believe that programs geared toward helping poor students or students of color get admission to selective or prestigious colleges are effective in preparing young people for the future. This includes majorities of Gen Z adults (69%) and teens (65%).

- Most Americans (60%) believe student loan forgiveness of up to $10,000 is effective in preparing young people for the future. This includes three-fourths of adult Gen Zers (75%) and two-thirds of teen Gen Zers (66%).

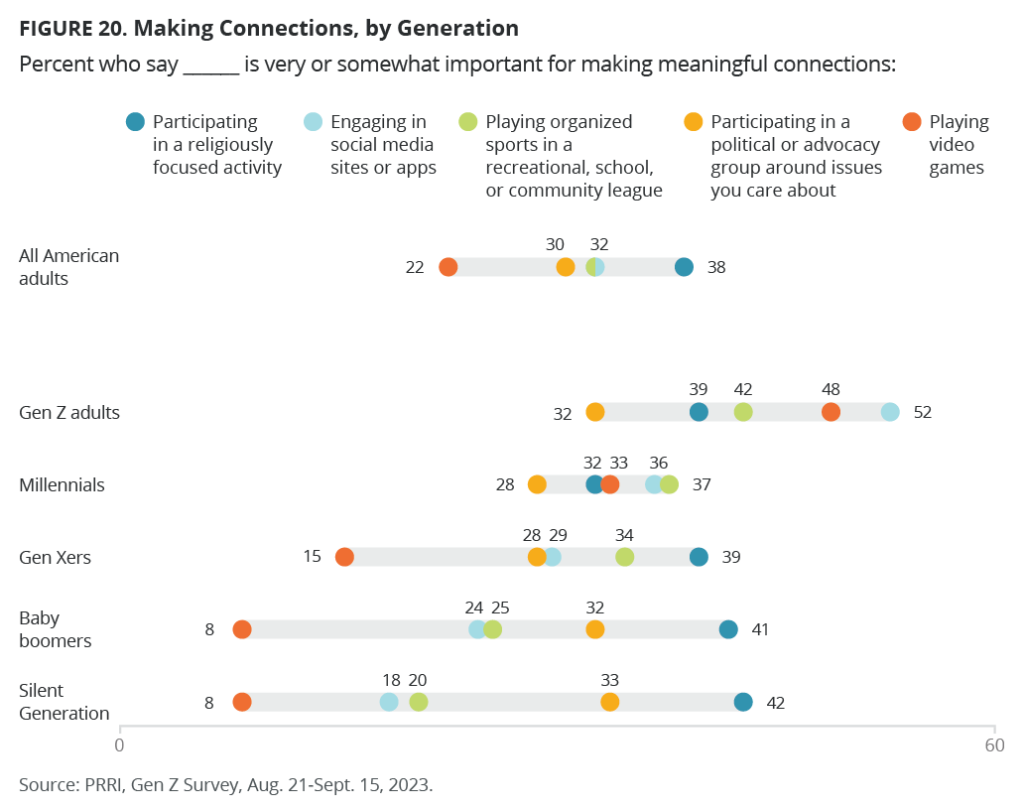

How Americans form meaningful connections differs across generations, with Gen Z forming more connections online.

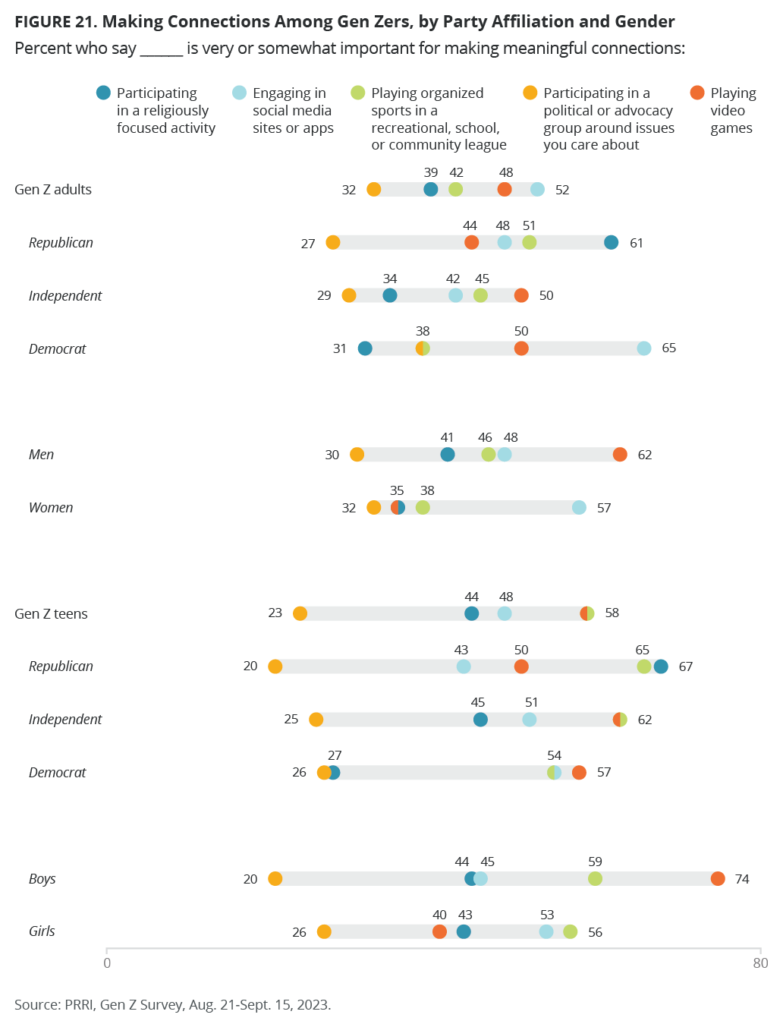

- Gen Z adults are more likely than older generations to say that social media (52%), organized sports (42%), or video games (48%) are important for making meaningful connections. They are just as likely as older Americans to find meaning in religious or political activities.

- Gen Z teens are more likely to find meaning in playing organized sports (58%) than Gen Z adults (42%). Gen Z men and boys often find meaningful connections playing video games, while Gen Z women and girls are more likely to use social media for meaningful engagement.

- Many Gen Z Republicans form meaningful connections in religiously focused activities, whereas Gen Z Democrats are more likely to find connection through social media sites or apps.

Gen Z adults, along with their millennial counterparts, hold little trust in America’s political institutions, but they participate in many political activities at similar or higher rates than older Americans. Gen Z teens also distrust political institutions, but they are less politically active than Gen Z adults.

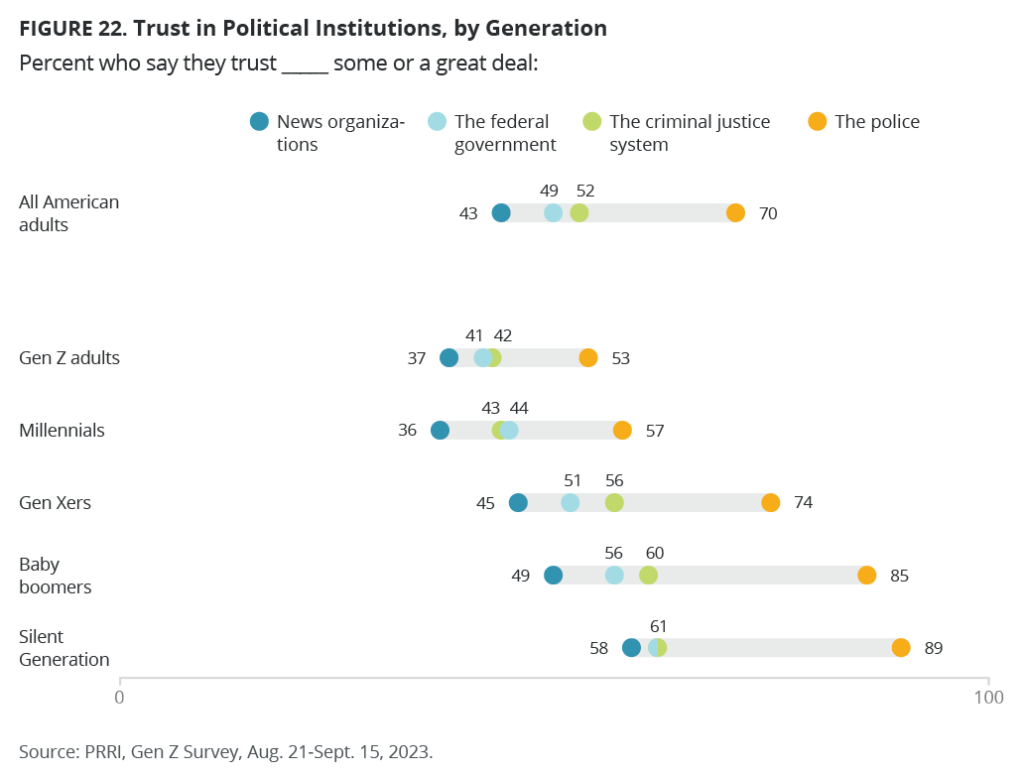

- While 70% of American adults hold some or a great deal of trust in the police, Gen Zers (53%) and millennials (57%) are less likely to do so. Gen Zers and millennials also hold less trust in the criminal justice system and the federal government compared with older Americans.

- Roughly 7 in 10 Americans (69%) believe that voting is the most effective way to create change in America; however, Gen Z adults (58%) and Millennials (60%) are significantly less likely than Gen Xers (70%), Boomers (80%), and members of the Silent Generation (85%) to agree that voting is the most effective way to create change in America.

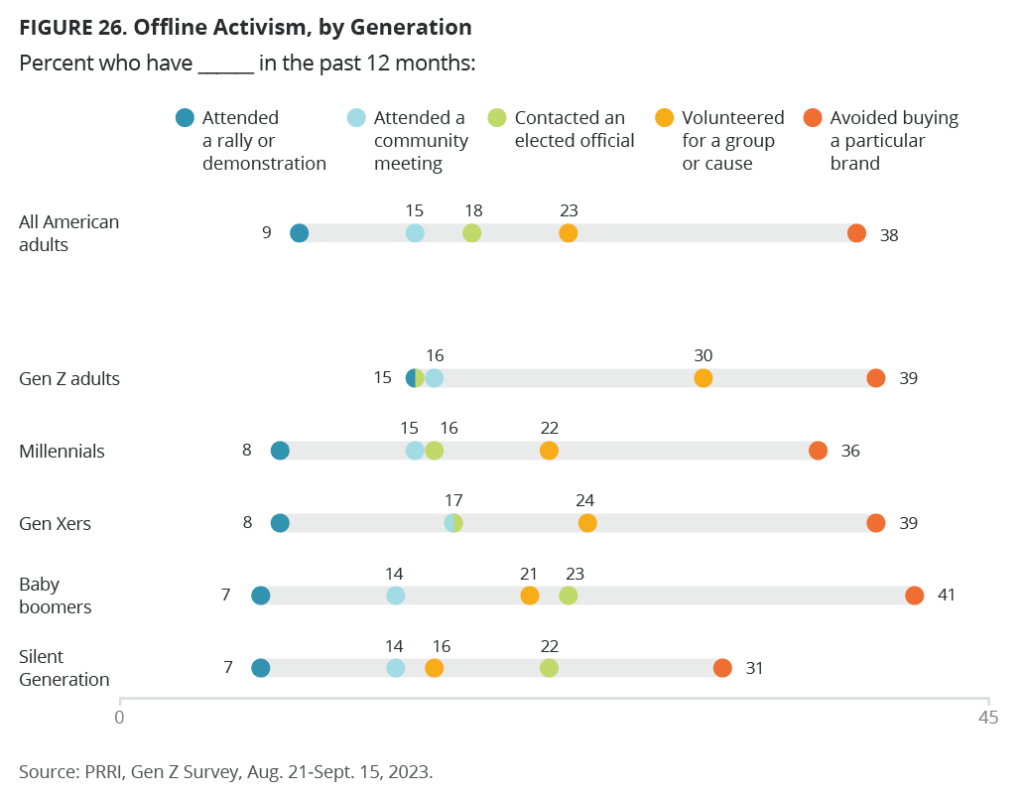

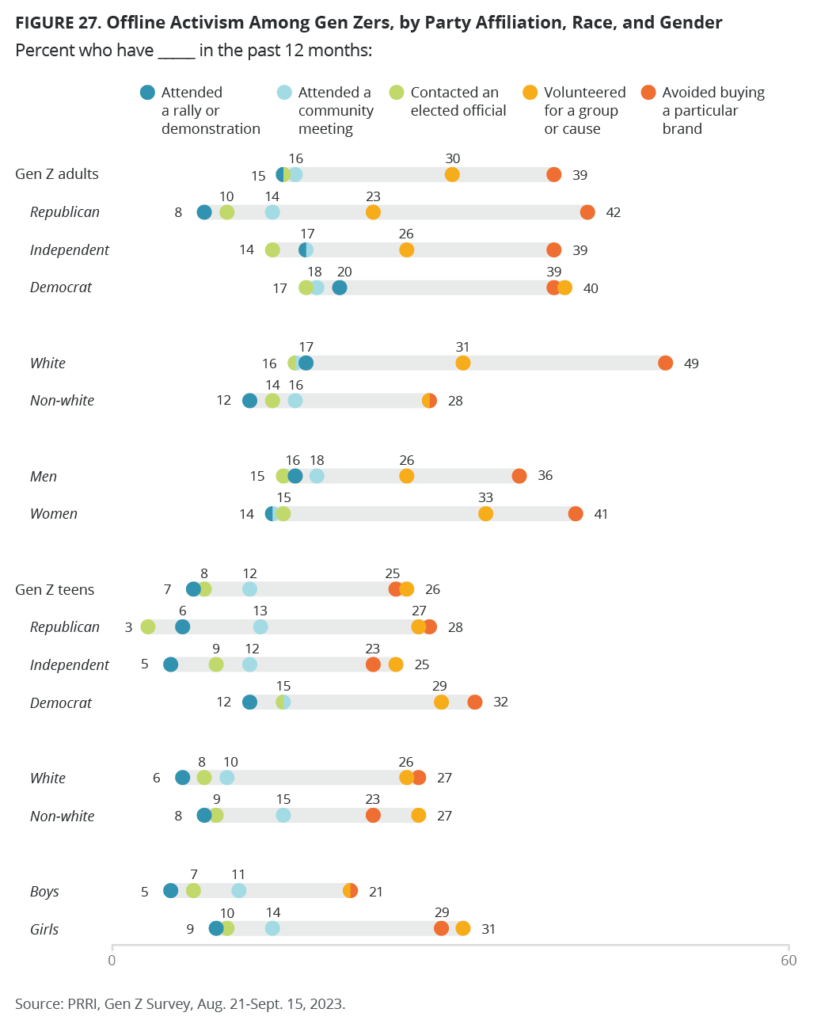

- Gen Z adults engage in online political activities at rates similar to or higher than older Americans, and they volunteer and attend political rallies at higher rates. Gen Z teens participate in politics at much lower rates than Gen Z adults.

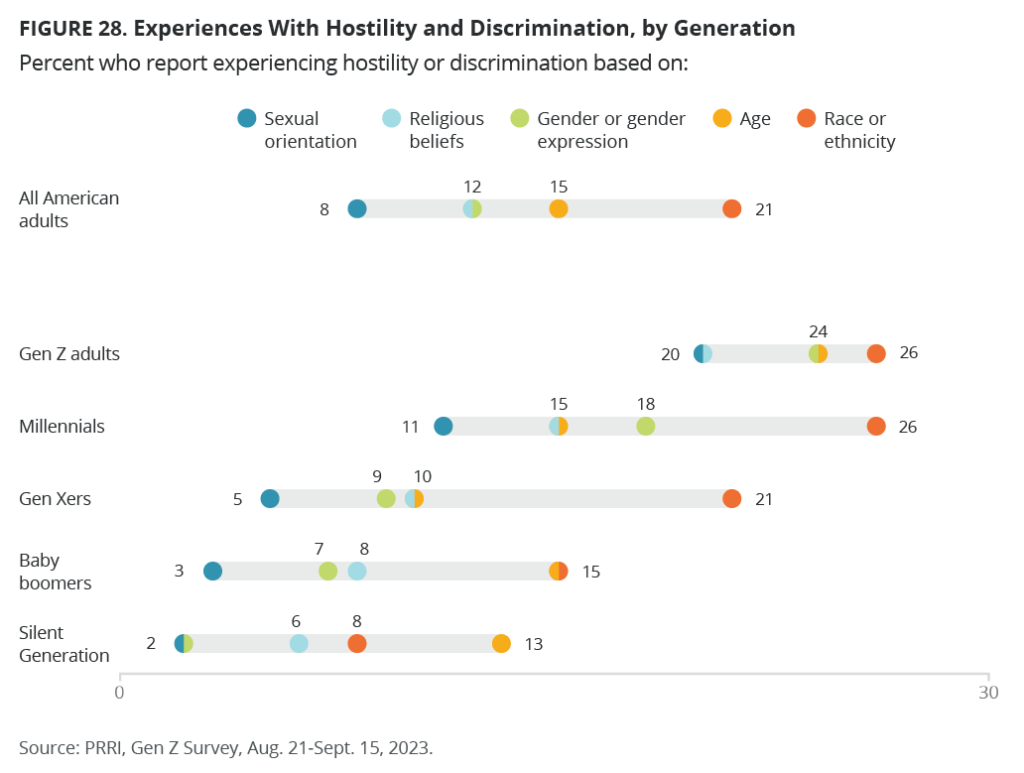

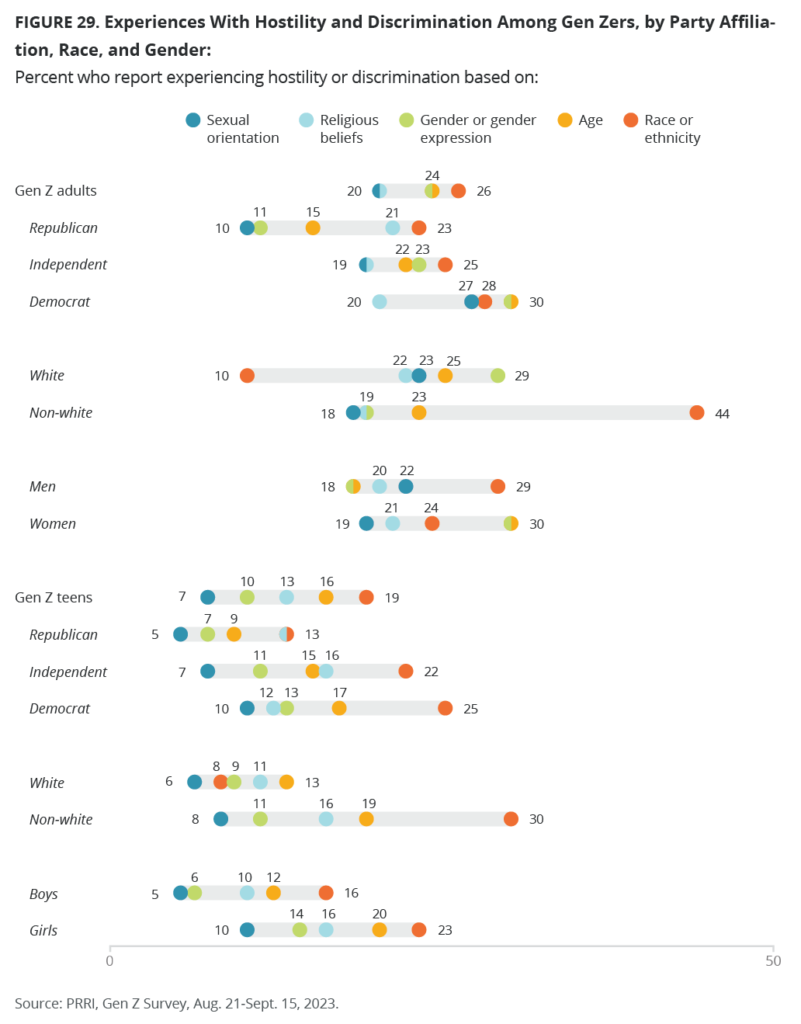

Gen Z adults report more experience with hostility and discrimination than older Americans or Gen Z teens.

- Approximately 1 in 5 Gen Z adults say they have personally experienced hostility or discrimination based on their race, age, gender or gender expression, religious beliefs, or sexual orientation. This rate is lower among older generations, except for millennials, who report experiencing race-based discrimination at a rate similar to Gen Z adults.

- Non-white Gen Z adults are more than three times as likely as their white counterparts to experience discrimination based on their race or ethnicity. Overall, Gen Z teens report fewer experiences with discrimination than Gen Z adults.

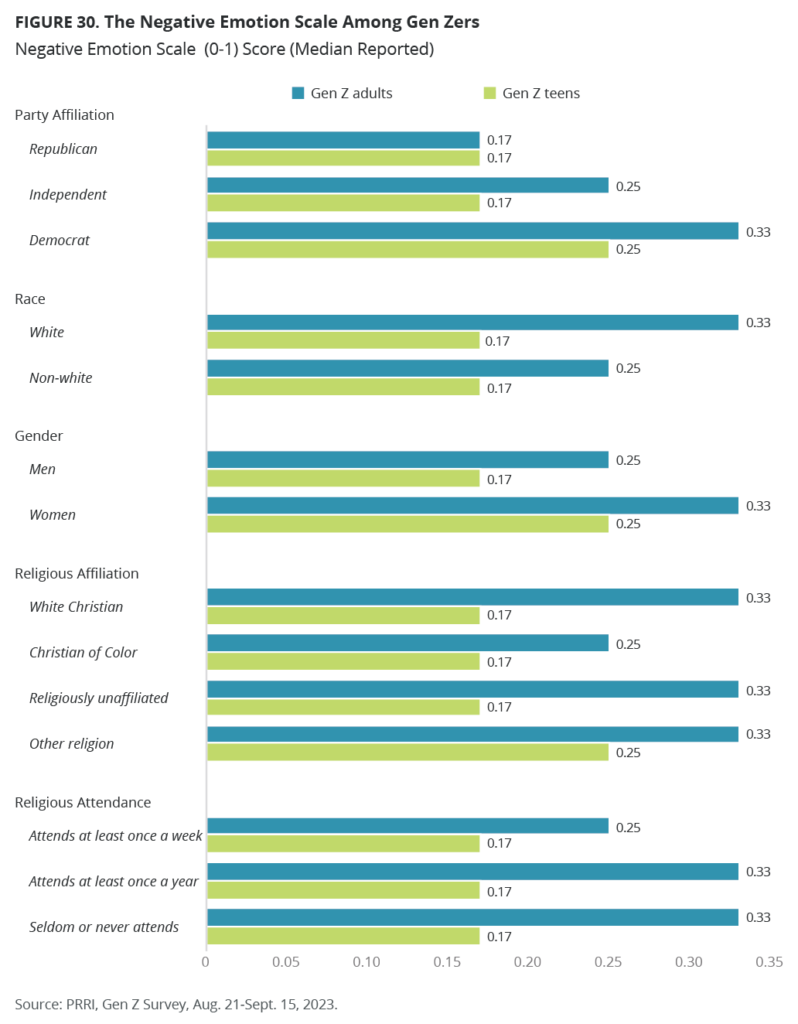

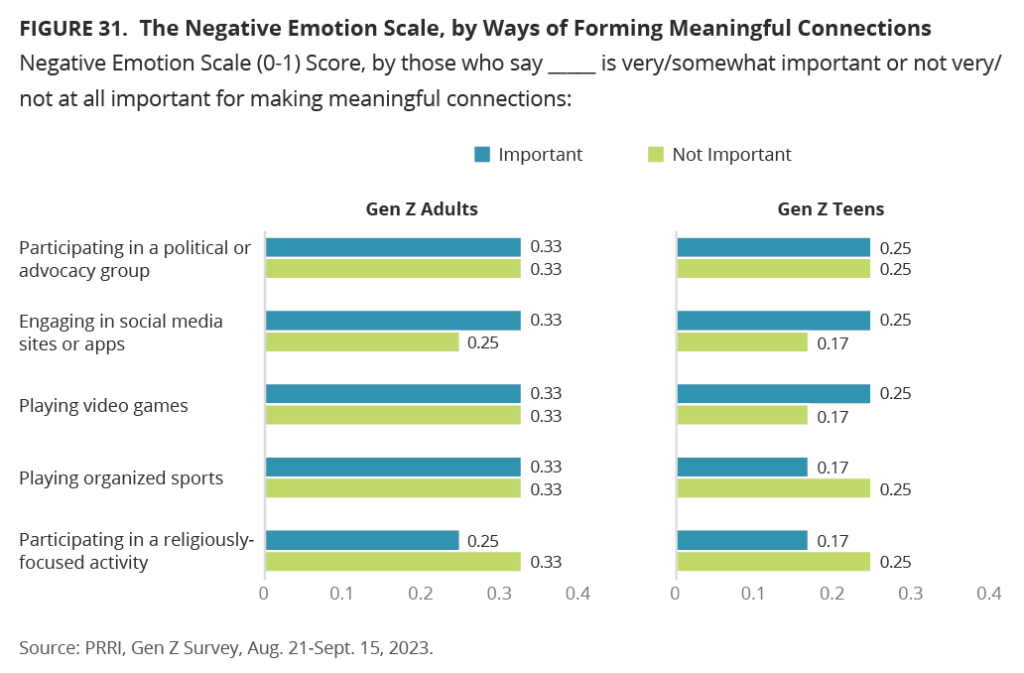

Gen Z adults are consistently more likely than older generations and Gen Z teens to experience negative emotions often or almost all the time. Negative emotions are more common among Gen Z Americans who rely on social media to make meaningful connections.

- Gen Z adults are consistently more likely than Gen Z teens to experience negative emotions often or almost all the time. They are more likely to feel anxious (38% vs. 18%), lonely (25% vs. 10%), depressed (24% vs. 8%), or angry (20% vs. 12%), and are less likely to feel hopeful (49% vs. 57%).

- Gen Z Democrats, women, and teen girls report feeling more negative emotions than Gen Z Republicans, men, and teen boys. White Gen Z adults report feeling more negative emotions than their non-white counterparts.

- Gen Zers who make meaningful connections through in-person activities, such as religious activities or sports, report feeling fewer negative emotions, while Gen Zers who make meaningful connections through social media sites report feeling more negative emotions.

Introduction

Members of Generation Z are beginning to come into their own politically, socially, and culturally as many Zoomers reach adulthood. Generation Z is the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in our nation’s history, with roughly half of Gen Zers identifying as non-white.[1] Gen Z adults also identify as part of the LGBTQ community at much higher rates than older Americans. Like millennials before them, Gen Zers are also less likely than older generations to affiliate with an established religion.

Generations are defined as groups of individuals who are born in the same time frame and who, according to generational scholar Jean Twenge, “experience roughly the same culture growing up.”[2] Although the specific years may vary, many scholars recognize Generation Z as those Americans born between 1997 and 2012, and we use that range in this survey report.

Generational analysis[3] is a useful analytical tool because major cultural, political, and economic events can impart a form of generational consciousness that deeply impacts the political orientations and habits of adults for decades.[4] Generation Z has come of age during a particularly tumultuous time, beginning with the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol after President Trump refused to concede his loss in the 2020 presidential election. Sometimes referred to as the Lockdown Generation, Gen Z has had to grapple with an unprecedented epidemic of school shootings. They are also clear-eyed about the existential threat that climate change poses to their futures. These concerns have prompted many Gen Zers to take to the streets and organize in their communities.

Digital natives, Gen Z Americans are the first generation to have been born after the release of the smartphone, and the social media habits they have developed as children and as young adults distinguish them from older generations — often in ways that have a negative impact on their mental health and their ability to form strong interpersonal relationships. Compared with previous generations, members of Generation Z are delaying many of the markers of adulthood, including marriage and buying a home. That delay is partly linked to economic pressure, which, for many Zoomers, includes massive college student loan debt, along with a high cost of living in the wake of significant inflation for the past several years.

This report considers what sets members of Generation Z apart from older generations in terms of their political and cultural values, their faith in communities and political institutions, and their views about religion and the importance of diversity and inclusion in U.S. democracy.

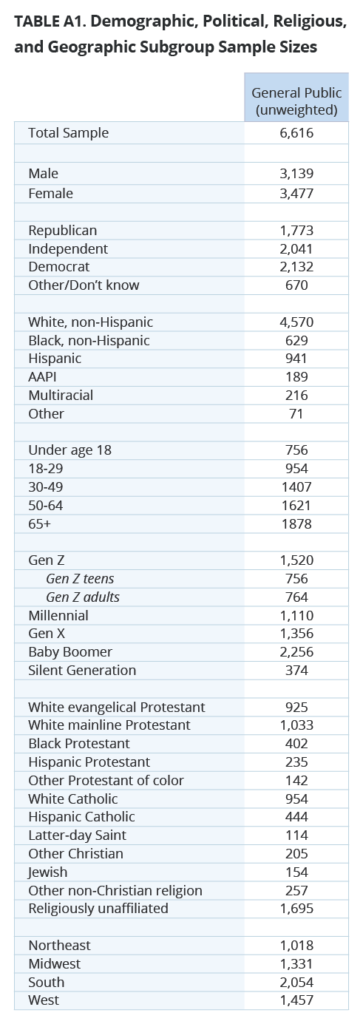

First, we share the results of a national survey of all Americans that includes oversamples of Generation Z, including both Gen Z adults (aged 18 to 25) and Gen Z teens (aged 13 to 17). In presenting generational comparisons, we examine differences between Gen Z adults and millennials, Gen Xers, baby boomers, and members of the Silent Generation, but we also focus on comparisons between Gen Z adults and Gen Z teens. It is worth noting that when we refer to “all Americans” in this study, we are referring to adult Americans who are 18 and older.

Unlike Gen Z teens, Gen Z adults are now eligible to vote — or have already voted — and largely face different life responsibilities. As they leave their adolescence behind, Gen Z adults are establishing their own paths, and cultivating their own identities and viewpoints as they gain independence and autonomy from their parents. Developmentally, Gen Z teens are distinct from Gen Z adults, as they are just beginning to learn how to better regulate their emotions, build relationships with their peers and adults, and grapple with larger questions about their role in their community and the larger world — including questions about politics. While the political viewpoints of Gen Z teens are still forming, their inclusion in the study gives us some sense of what their political priorities and habits may look like in the future, as they, in turn, become new voters in the next few years.

Second, our study draws from the focus group research as well. PRRI convened ten virtual focus groups with Gen Z adults, aged 18 to 25, from across the United States, who were selected to represent a wide cross section of Gen Zers, including the following: one white group with two years of college or less, one white group with a four-year college degree, one Black group, one Hispanic group, one LGBTQ group, one group of Gen Zers who identified as politically independent, one Democratic group of Gen Z women, one Democratic group of Gen Z men, one Republican group of Gen Z women, and one Republican group with Gen Z men. These focus groups provided an environment for conversations about participants’ views on generational differences, diversity, the economy, political institutions, and the role of religion in Gen Zers’ lives, helping to provide more context for our survey findings. [5]

Profile of Gen Z Americans Compared With Older Generations

Demographics

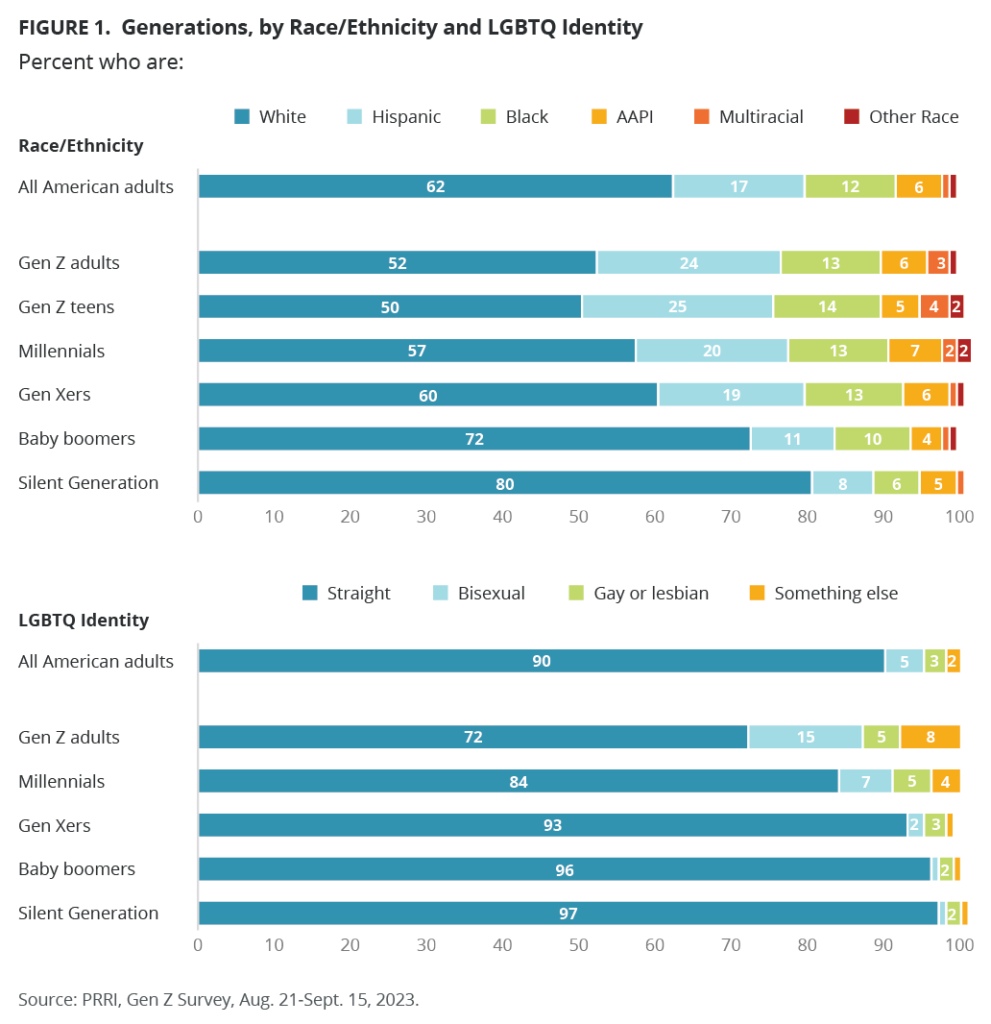

Our PRRI 2023 Gen Z survey shows that half of Gen Z adults (52%) identify as white, compared with 57% of millennials, 60% of Gen X, 72% of baby boomers, and 80% of the Silent Generation. Gen Z adults are more likely to identify as Hispanic (24%), compared with 20% of millennials, 19% of Generation X, 11% of baby boomers, and just 8% of the Silent Generation. Around one in ten or fewer across all generations identify as Black, Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI), multiracial, or another race. Gen Z teens look comparable to Gen Z adults in our study on racial and ethnic measures. [6]

Gen Z adults are significantly more likely than older generations to identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or something else, with 28% identifying as LGBTQ, compared with 16% of millennials, 7% of Generation X, 4% of baby boomers, and 4% of the Silent Generation. Gen Z teens were not asked about LGBTQ identification.

Party Affiliation

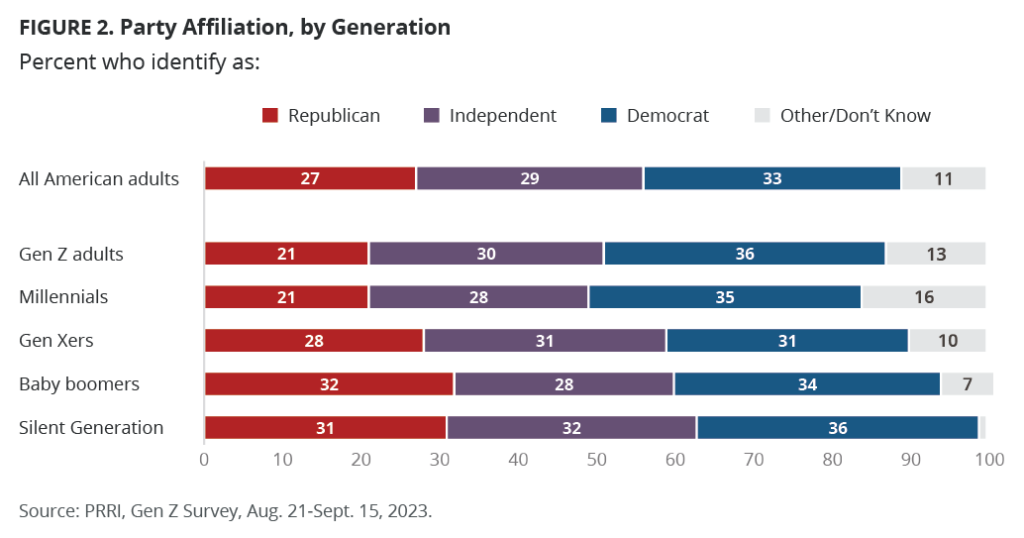

Gen Z adults (21%) are less likely than Gen Xers (28%), baby boomers (32%), and members of the Silent Generation (31%) to identify as Republican, but they do not differ from millennials (21%). Gen Z adults (36%) identify as Democrats at a rate similar to that of the Silent Generation (36%), millennials (35%), and baby boomers (34%). Gen Xers identify as Democrats at a slightly lower rate (31%). Gen Z adults identify as independents at similar rates to other generational cohorts.

Gen Z teens are as likely as Gen Z adults to identify as Republicans (both about 22%) and as independents (35% vs. 30%, respectively), but they are notably less likely to identify as Democrats (27% vs. 36%). When the “independent” and “other/don’t know” categories are combined, however, more than half of Gen Z teens (51%) do not identify with either major political party, compared with 43% of Gen Z adults.

Our survey finds that about two-thirds of Gen Z teens (65%) match their parents’ party affiliation, with 87% of Republican teens and 86% of Democratic teens reporting that they support the same party as their parents. Two-thirds of teens who identify as independent (66%) also have parents who are political independents. [7]

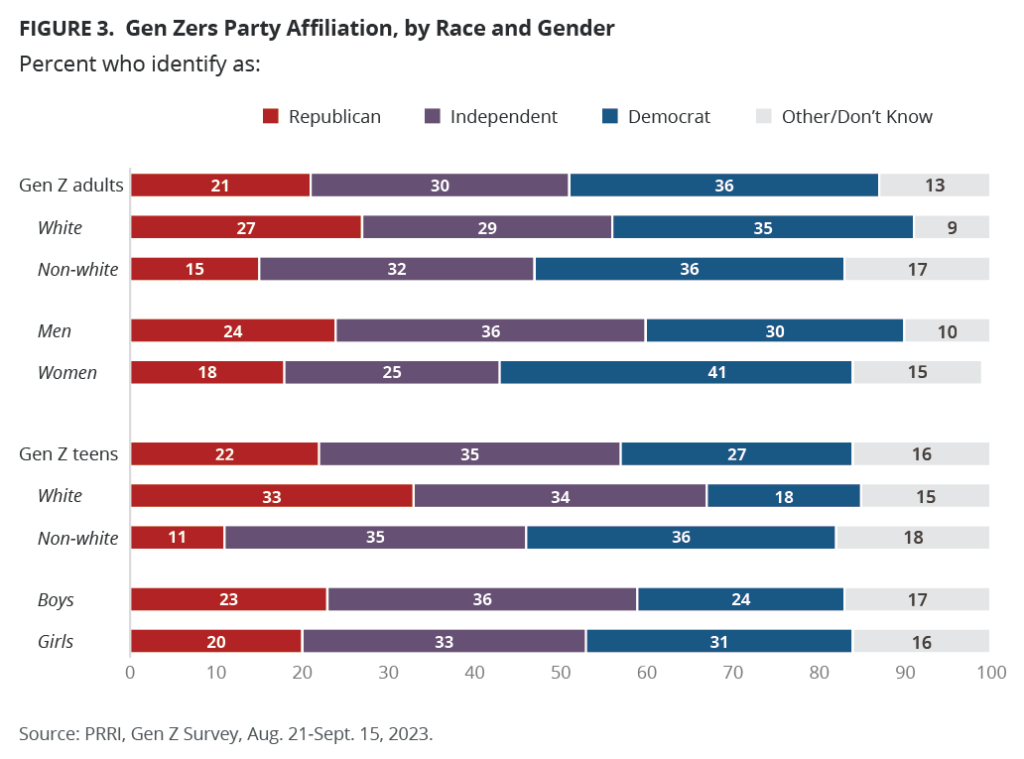

Among white Gen Zers, about one-third of teens identify as Republican (33%) or independent (34%), compared with 27% and 29%, respectively, of Gen Z adults. However, white Gen Z teens are half as likely as white Gen Z adults to identify as Democratic (18% vs. 35%). By contrast, there is little variation between non-white Gen Z adults and teens when it comes to partisanship: in both cases, non-white Zoomers are more likely to identify as Democratic or independent than Republican.

There is a pronounced gender gap in partisanship among Gen Z adults, with Gen Z women being more likely than Gen Z men to identify as Democratic (41% vs. 30%, respectively). Gen Z men and Gen Z women identify as Republican (24% and 19%, respectively) and independent (36% and 29%, respectively) at similar rates.[8]

There is less variation by gender among Gen Z teens, with the exception that girls are more likely than boys to identify as Democratic. While Gen Z men and boys look similar in terms of partisan identification, Gen Z girls are notably less likely than Gen Z women to identify as Democratic (41% vs. 31%) and more likely to identify as independent (33% vs. 25%).

Political Ideology

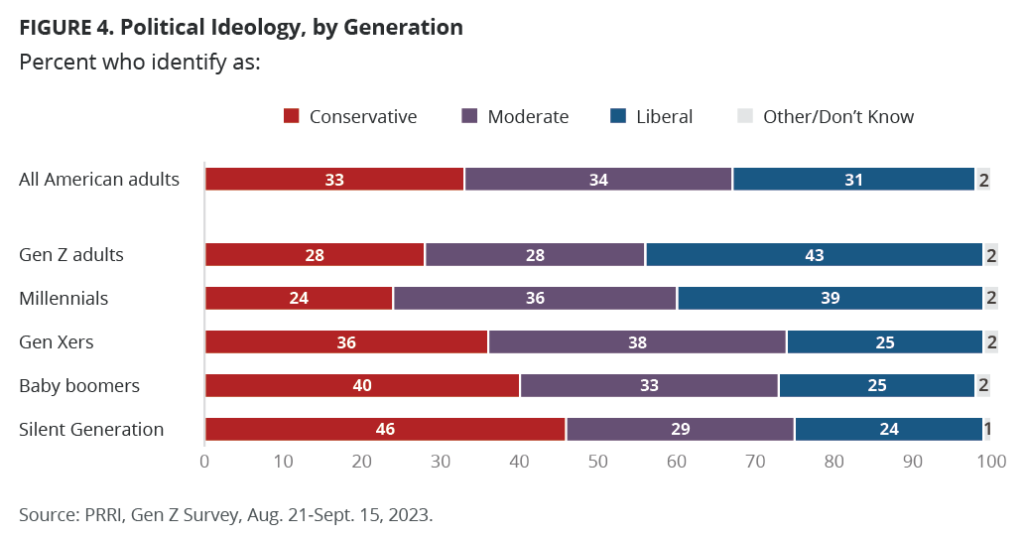

With the exception of millennials (24%), Gen Z adults (28%) are notably less likely than other generational cohorts, including Gen X (36%), baby boomers (40%), and the Silent Generation (46%), to identify as conservative. By contrast, Gen Z adults are the most likely of any generation to identify as liberal, at 43%, compared with one in four members of the Silent Generation (24%), baby boomers (25%), and Gen Xers (25%), and 39% of millennials. With the exception of the Silent Generation (29%), Gen Z adults (28%) are the least likely to identify as moderate.

Gen Z teens are far more likely than Gen Z adults to lean toward the political center, with 44% identifying as moderate. Gen Z teens and Gen Z adults are equally likely to identify as conservative (30% for both), but teens are notably less likely to identify as liberal (24%) than Gen Z adults.

Race and gender are also linked to ideological self-identification among Gen Zers. White Gen Z adults are more likely than their non-white counterparts to identify as conservative (32% vs. 23%), but there is no significant difference in the proportion who identify as liberal. There is also a pronounced gender gap among Gen Z adults, with 47% of Gen Z women and 38% of Gen Z men identifying as liberal. While Gen Z men are slightly more likely to identify as conservative than Gen Z women, this difference is not statistically significant.

Non-white teens are less likely than white teens to identify as conservative (21% vs. 38%), but they are markedly more likely to identify as moderate (51% vs. 36%). One notable difference between Gen Z adults and teens is that fewer teens, both white and non-white, identify as liberal. This gap is especially pronounced among white Zoomers, with just 22% of white Gen Z teens identifying as liberal, compared with 46% of white Gen Z adults. By contrast, there are no significant differences in political ideology by gender among Gen Z teens.

Religious Affiliation

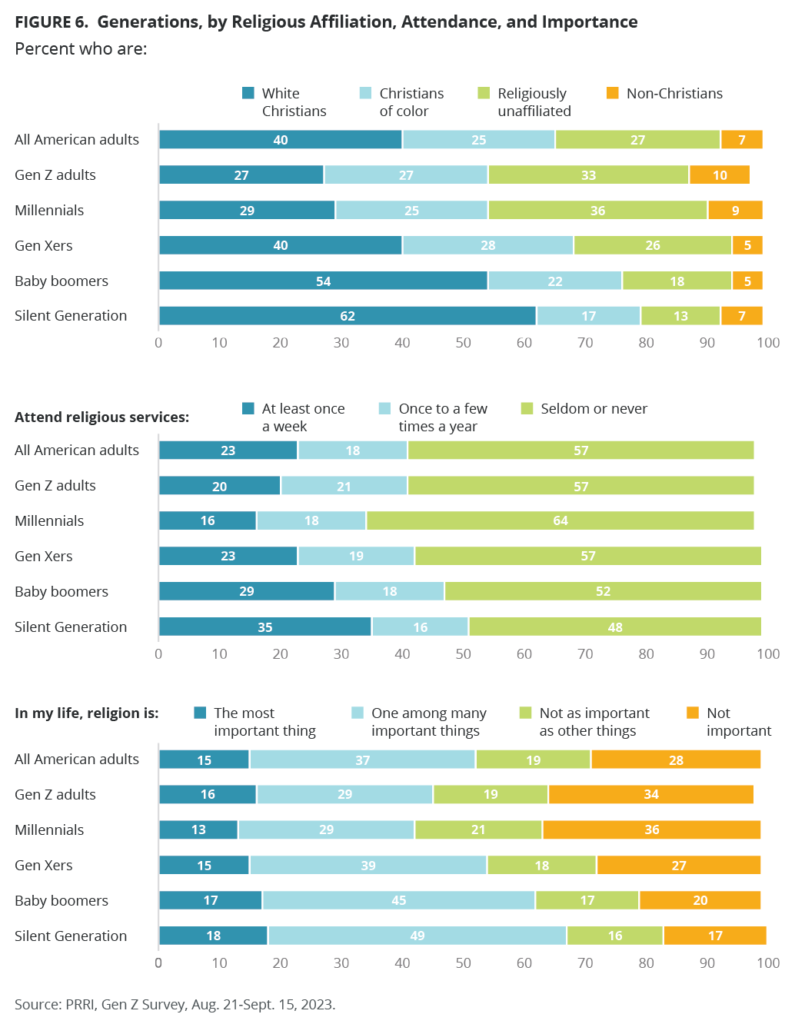

Gen Z adults are notably less likely to identify as white Christians and more likely to identify as religiously unaffiliated than older generations, with the exception of millennials. Roughly three in ten Gen Z adults (27%) and millennials (29%) identify as white Christians, compared with 40% of Gen X, 54% of baby boomers, and just 62% of the Silent Generation. Similarly, about one-third of Gen Z adults (33%) and millennials (36%) identify as religiously unaffiliated, compared with 26% of Gen Xers, 18% of baby boomers, and just 13% of the Silent Generation. Roughly one in four Americans across all generations identify as Christians of color, while one in ten (or less) identify with a non-Christian religion.

Gen Z adults (20%) are less likely than baby boomers (29%) and the Silent Generation (35%) to attend religious services frequently, but they do not differ substantially from millennials (16%) and Gen Xers (23%). By contrast, members of the Silent Generation are the least likely to report seldom or never attending religious services, with 48% saying this is the case, compared with 57% of both Gen Z adults and Gen Xers and 52% of baby boomers. Millennials (64%) are the most likely to report seldom or never attending religious services. About two in ten across all generations report attending religious services once or twice a month or a few times a year.

Less than half of Gen Z adults (45%) and millennials (42%) report that religion is the most important thing in their lives or one among many important things, compared with the majority of Gen Xers (54%), baby boomers (62%), and the Silent Generation (67%). By contrast, the majority of Gen Z adults (53%) and millennials (57%) say that religion is not as important as other things or not important at all, compared with 45% of Gen Xers, 37% of baby boomers, and 33% of the Silent Generation.

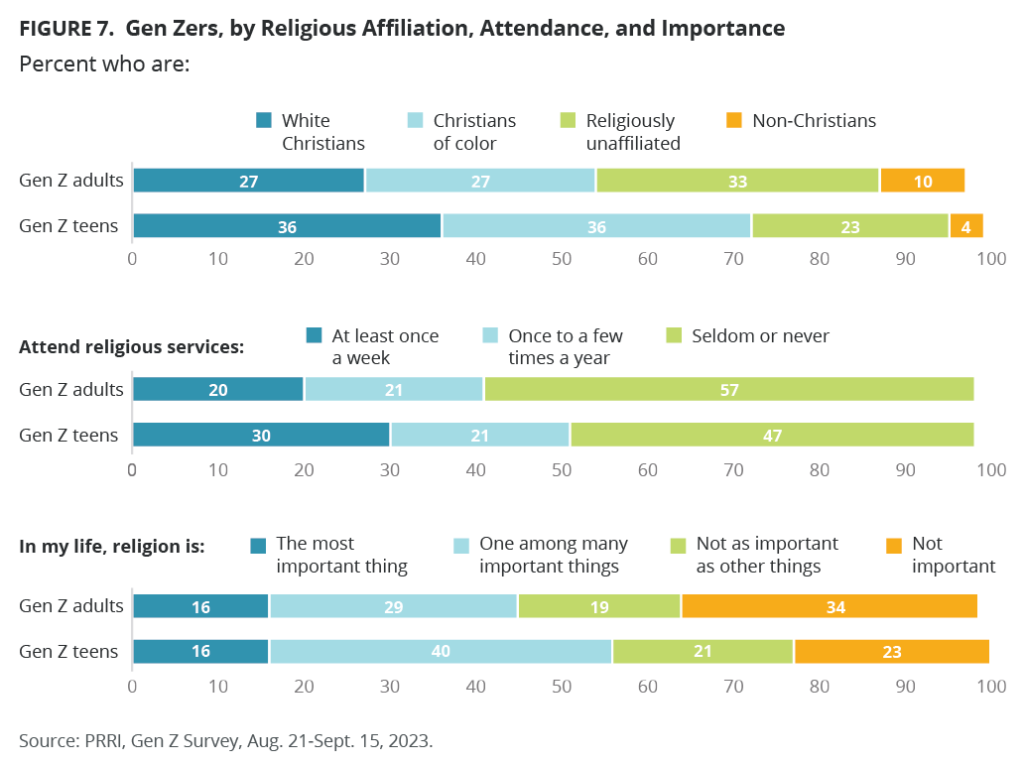

Gen Z teens are more likely to identify as Christians than Gen Z adults. More than one-third of Gen Z teens identify as white Christians or as Christians of color (both 36%), compared with 27% of Gen Z adults. By contrast, Gen Z teens are ten percentage points less likely than Gen Z adults to identify as religiously unaffiliated (23% vs. 33%) and six percentage points less likely to identify with a non-Christian religion (4% vs. 10%).[9] In fact, strong majorities of Gen Z teen Christians follow the same religion as their parents. More than eight in ten white Christian teens (83%) and Christian teens of color (85%) report belonging to the same religion as their parents, compared with 68% of religiously unaffiliated teens.

Similar proportions of Gen Z teens and adults report not attending religious services frequently (both 21%), but Gen Z teens are ten percentage points more likely than Gen Z adults to say they attend at least once a week (30% vs. 20%) and ten percentage points less likely to say they seldom or never attend (47% vs. 57%).

Gen Z teens (56%) are also more likely than Gen Z adults (45%) to report that religion is the most important thing in their lives or one among many important things, and they are less likely to say that religion is not as important as other things or not important at all (44% vs. 53%).

Focus Group Insights:

Religion and Gen Z

Gen Z adults were asked about their religious upbringing, their current religious practices, and their views on organized religion. Some Gen Z adults said their religious upbringing played an important role in the development of their values and beliefs, noting that they still practice their faith today and are grateful for the community connections they have developed through their religious institutions.

“[I] love going to church every Sunday and being able to worship with those around me. And we go to a fellowship group. It’s five other families and we … talk about things that encourage us, share prayer requests, and lean on each other for support.… That has just been a really great community.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“Growing up in a Christian household, the main thing that I carry on that I’m gonna pass to my kids … is faith in God. It’s No. 1, it’s No. 1. I realize in my life that without God I don’t really have anything. He’s my road. When I don’t know which way to go, that’s who I turn to.”

— Female participant in the Black group

“I was raised as a Muslim…. Since then, I’ve been trying to learn more about it and I’ve actually grown up to really appreciate the values, and I have used Islam as a guiding force in my life, emphasizing values and compassion, justice. This means a lot to me and formed my opinions and beliefs…. My faith actually teach[es] me to treat everyone with respect and empathy.”

— Male participant in the Democratic group

Other Gen Zers were appreciative of the religious upbringings their families provided, even if, as young adults, they have adapted their beliefs and religious behaviors to better fit their own views and needs. In some cases, these Gen Zers have stopped attending religious services regularly but have developed their own private religious practices. Others noted that they intend to resume engagement with religious communities when they have their own families.

“I do follow the principles of, like, praying, believing in God, that God is the way and the faith, but there are definitely some things, like, I don’t follow.… I still feel strongly in the beliefs of being kind to others, respecting others. Those are my core beliefs. Not cheating, stealing, things like that. But when I step back from Christianity… [t[here’s certain things that I just don’t agree with. So, even though I still remain strong in my faith … any views that don’t serve me, I kind of just separate.”

— Female participant in the Black group

“I never got to sleep in [on Sundays.] So, yeah, I decided to keep going and I kind of backed off in college. I still go on the big holidays: Easter, Christmas. But I find myself every once in a while in a tough spot when something’s going wrong and I just end up some way, somehow at a church…. I find solace in it still. I may not still go every week, but it’s still a pretty big part of life.”

— Male participant in the white, college-educated group

“I was in a Catholic family, and then in high school and college I saw a lot of people being hypocrites, particularly religious people…. Eventually, I came back to it because I saw there was also a lot of good in it. Just because there’s a few bad apples or some bad apples doesn’t mean I want to kind of throw the whole thing away. I learned the faith in English, Spanish, and Latin, just because my mom was just that heavily invested into it when I was little…. And I want eventually my son or my kids to kind of grow up in the same way and kind of have them do the same thing.”

— Male participant in the Hispanic group

Some Gen Zers acknowledged that though they are not actively practicing a religious tradition, they are still seeking a spiritual path or trying to figure out where they land when it comes to religion, spirituality, and finding deeper meaning in life.

“[A]lthough I’m not a practicing religious person, I believe that your spirituality is just as important and that it can be your set of principles…. So if I have a certain set of principles that I want to follow, then I need to practice that in my life and show compassion to others and do what I believe is right. So I guess that’s kind of like spirituality.”

— Female participant in the Hispanic group

“[I] am a religious spiritual person, and so I do turn to God for my meaning of life and for my quality of life. Being able to look to that when I’m feeling helpless, when I’m feeling down in the dumps, that’s where I find my meaning and my love.”

— Female participant in the Republican group

Finally, there were Zoomers who either grew up without any religious background or were raised in a faith tradition that they no longer practice. Among formerly religious participants, some gradually drifted away from their practice. Others left because they became jaded about organized religion, citing what they viewed as the hypocrisy of religious leaders, often in relation to sexual abuse scandals or other corruption. Others left because they felt that religious institutions placed too much emphasis on raising money. Still others left their faith tradition because they disagreed with its views on politics or its treatment of LGBTQ people, or because they found their religious institution to be too strict and confining.

“I think that it’s possible that you can practice [religion] and be a great person, but I think a lot of the values in most religions tend to boil down to those themes of discrimination and control, bigotry. So that’s something my family I’ve created has left behind, and I’ve noticed a lot of people in my generation, my friends …. have also been leaving it behind.”

— Female participant in the LGBTQ group

“I grew up going to church and stuff. I’ve just slowly kind of backed away a little bit because it’s just way too overwhelming with the amount of politics that are in churches…. And it’s a shame that I don’t want to go to church anymore and I don’t want to be around churchgoers because the majority of the ones around me, at least, are very political, and I just don’t want anything to do with it.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“For the most part, it’s hard to trust religious institutions nowadays…. [R]eligion has shown itself to be about control over others and it’s really hard to trust them. I’m not saying there are not good religious institutions out there that are actually there to help and be of service for people, but I think there’s just a lot of people using that institution as a way to get what they want.”

— Male participant in the LGBTQ group

Trust in Organized Religion

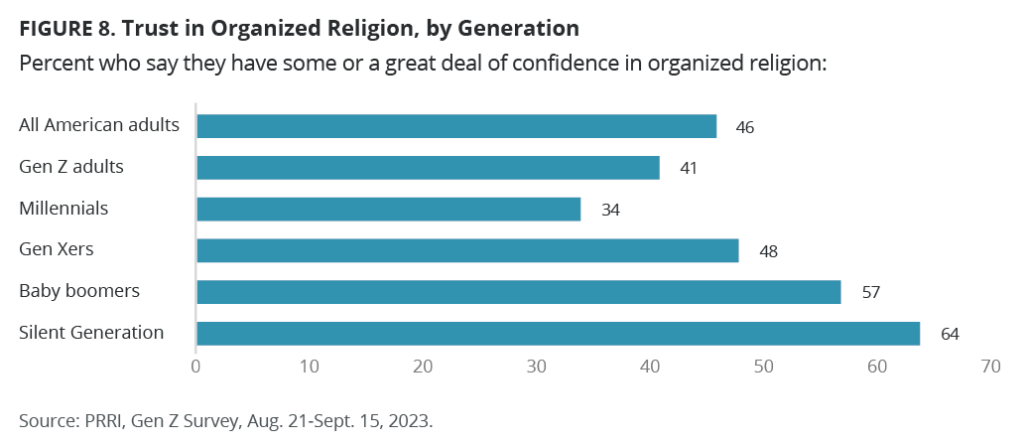

PRRI also asked Americans how much confidence they have in organized religion. Nearly half of all Americans (46%) have some or a great deal of trust in organized religion, while the majority (53%) have little or no trust at all. More than four in ten Gen Z adults (41%), around one-third of millennials (34%), and less than half of Gen Xers (48%) have at least some trust in organized religion, while 57% of baby boomers and 64% of the Silent Generation say the same.

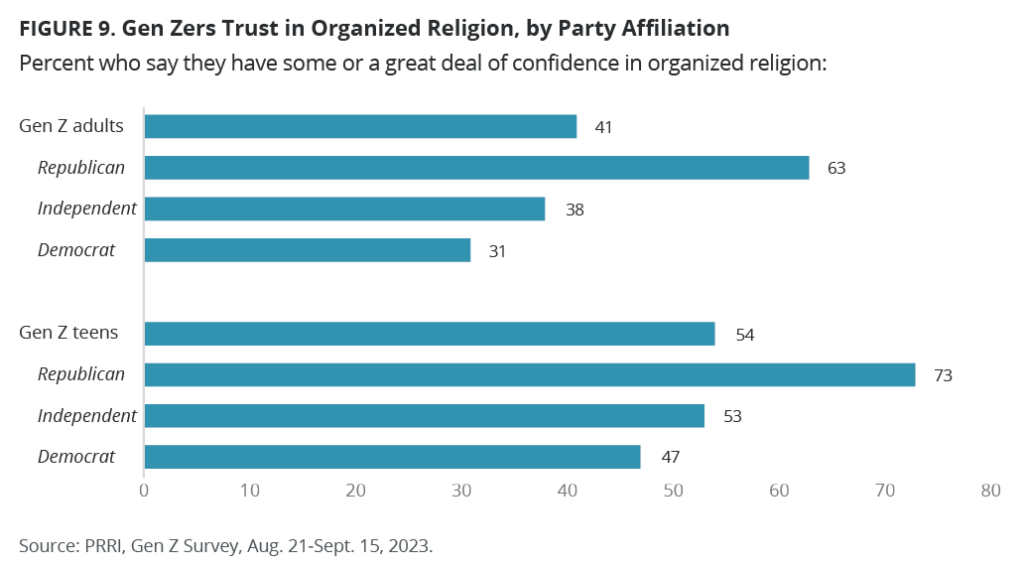

Gen Z teens are notably more likely than Gen Z adults to trust organized religion (54% vs. 41%). Among Gen Z adults, Republicans (63%) are about twice as likely as independents (38%) and Democrats (31%) to trust organized religion. Similarly, less than half of Gen Z men (45%) trust organized religion, compared with 36% of Gen Z women.

Gen Z teens of all political party affiliations trust organized religion more than their adult counterparts. Majorities of Republican teens (73%) and independent teens (53%) trust organized religion, compared with less than half of Democratic teens (47%).

Generational Change

Attitudes on Different Generations and Political Power

America’s Problems Won’t be Solved With Older or Younger Generations in Power

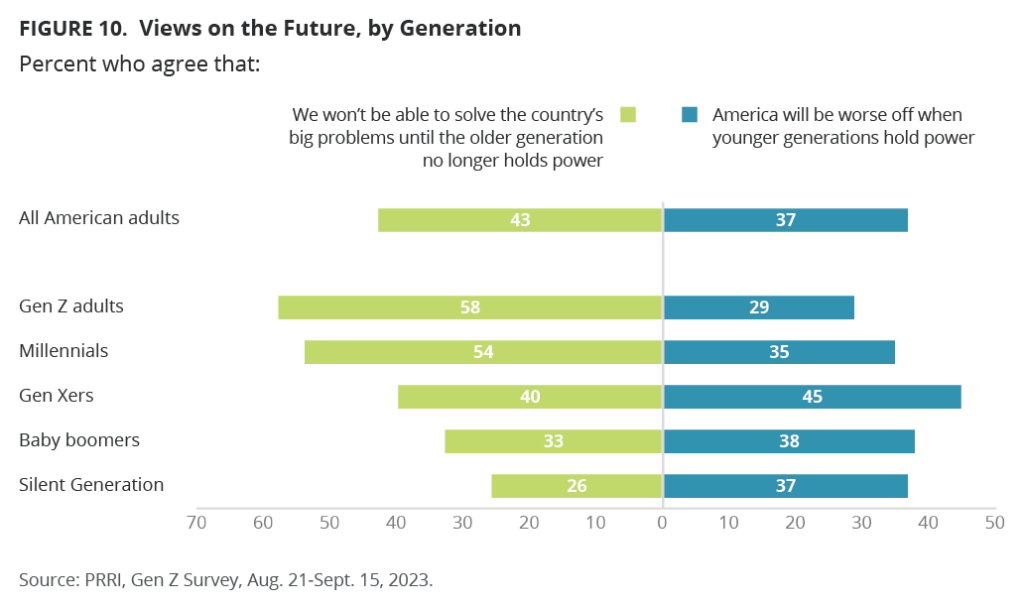

More than four in ten Americans (43%) agree with the statement “We won’t be able to solve the country’s big problems until the older generation no longer holds power.” The majority of Gen Z adults (58%) and millennials (54%) agree with that idea, compared with four in ten Gen Xers (40%), one-third of baby boomers (33%), and around one in four of the Silent Generation (26%).

In comparison, nearly four in ten Americans (37%) agree that “America will be worse off when younger generations hold power.” Unsurprisingly, Gen Z adults (29%) are less likely than older generations, including Millennials (35%), Gen Xers (45%), baby boomers (38%), and the Silent Generation (37%), to agree with this statement.

Gen Z adults (58%) are more likely than Gen Z teens (49%) to agree with the idea that the country’s big problems won’t be solved until the older generation is no longer in power. By contrast, Gen Z adults (29%) are notably less likely than Gen Z teens (37%) to believe that America will be worse off when younger generations hold power.

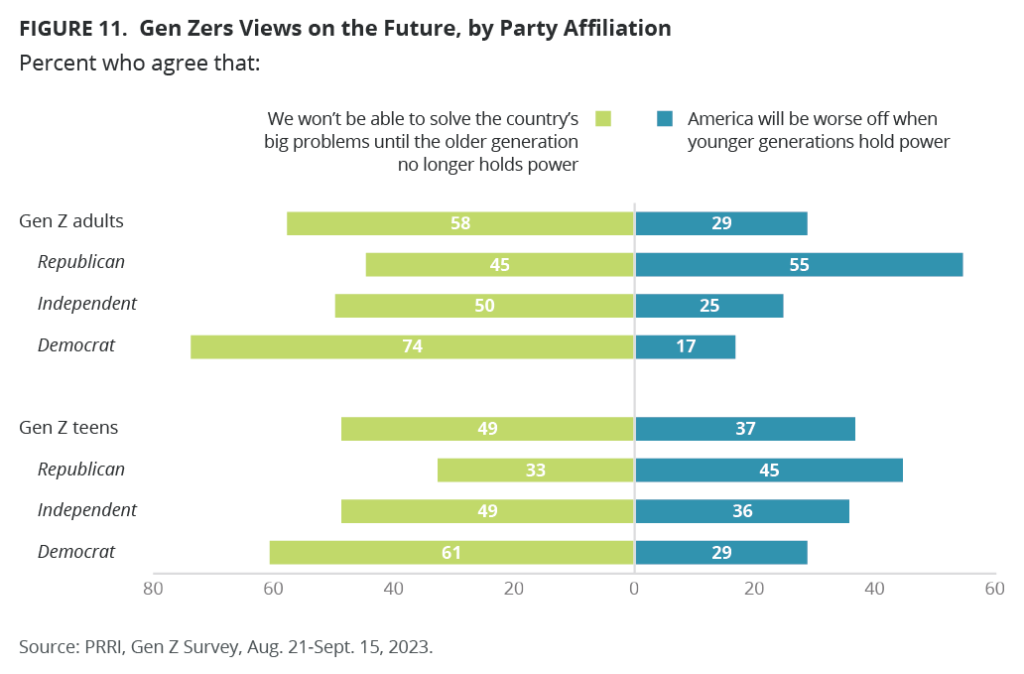

Yet, there are stark differences among Gen Zers when it comes to partisanship and views about generational leadership change. Among Gen Z Democrats, both adults (74%) and teens (61%) are far more likely than independents (both about 50%) and Republicans (45% and 33%, respectively) to believe that the country’s big problems won’t be solved until the older generation is no longer in power. By contrast, Gen Z Democratic adults (17%) and teens (29%) are less likely than Republicans (55% and 45%, respectively) to think things will become worse when younger generations hold power, but they do not differ significantly from independents.

While there are no significant differences by race and gender among Gen Z adults, non-white teens (54%) are more likely than white teens (45%) to agree with the idea that the country’s big problems won’t be solved until the older generation is no longer in power. However, white and non-white teens do not differ significantly on the question of whether America will be worse off when younger generations hold power.

Older and Younger Generations Do Not Understand the Struggles of Their Generations

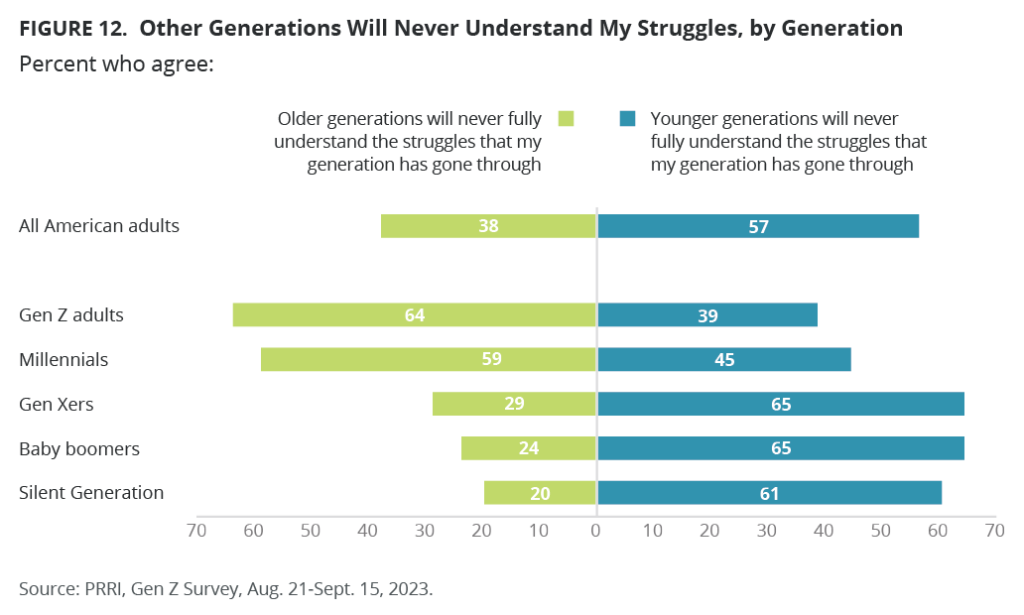

Americans tend to think that generations other than their own will never fully understand their struggles. They are more likely to believe this of younger generations (57%) than of older generations (38%). Majorities of both Gen Z adults (64%) and millennials (59%) believe that older generations will never fully understand their generation’s struggles, compared with 29% of Gen X, 24% of baby boomers, and 20% of the Silent Generation.

By contrast, older generations, including 65% of both Gen X and the baby boomers, and 61% of the Silent Generation, are more likely than younger generations — namely Gen Z adults (39%) and millennials (45%) — to say that the younger generations will never fully understand their generation’s struggles.

Gen Z adults (64%) are slightly more likely than Gen Z teens (58%) to say that older generations will never fully understand the struggles their generation has gone through. By contrast, Gen Z adults (39%) are less likely than Gen Z teens (44%) to say that younger generations will never fully understand the struggles of their generation.

Strong partisan and gender divides appear among Gen Z adults on this question, with Democrats (79%) and women (73%) more likely than independents (61%), Republicans (46%), and men (54%) to agree with idea that older generations will never fully understand the struggles their generation has gone through. Meanwhile, Democrats (36%) are less likely than Republicans (56%) to agree that younger generations will never fully understand their struggles.

There are no significant differences among Gen Z teens with respect to views about older and younger generations not fully understanding the struggles of their generation.

Focus Group Insights:

Gen Z’s Views on Generational Change

We asked Gen Z adults about the unique concerns and challenges their generation faces compared with older generations. Many Gen Zers said they wanted to see more generational diversity among those in government and other powerful positions, because they felt that older Americans failed to understand their struggles — particularly how much harder life is economically for Gen Zers than it was for their parents and grandparents at the same age.

“[O]ne of the big things that I’ve been thinking about lately is the fact that my mom went to college and her mom supported her in going to college. And if you had a college degree, you had a good life.… I feel like with my bachelor’s degree I don’t have that same quality of life. I feel like I have to go further and get more education, and that’s going to delay other goals that I have for my life as well, like raising a family and getting married.”

— Female participant in the Republican group

“When it comes to the older generation, I feel like they forget that they raised us…. Like they birthed us into this world, so instead of rushing us, like, `Oh, you gotta do that, you gotta do that,’ actually sit and understand where we are and try to come up with a solution with us, because you don’t have the solution…. So we gotta figure it out together at this point, you know what I mean?”

— Female participant in the Black group

Focus group participants discussed whether their generation was lazier or more entitled compared with their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. While a few participants agreed with this perception, the vast majority did not. In fact, many felt that although their economic future may be more precarious than previous generations experienced, their generation is more entrepreneurial and better equipped to deal with the careers of the future—and that members of their generation are tougher than often assumed.

“I think life today is, like, at a level of unseriousness, and I think life for my parents had a certain aspect of seriousness. They kind of had a plan or a vision of how they wanted their life to be. My parents are …[Haitian] immigrants, so they had a plan and a vision of why they came to America.… Today, we have a whole bunch of kids with, like, nothing to do, a bunch of energy but nowhere to place it. We have social media, we have all of these broad goals, like, we could be anything. We could literally be anything in the world, but we can’t. I feel like that’s where we’re at. Like, we see the fact that we could be anything in the world, but we can’t.”

— Female participant in the Black group

“Gen Z is tough. I think older generations think that we’re lazy and that we’re dumb, and we don’t care, and that’s very opposite. I mean, we have a lot on our shoulders, as we’ve discussed, with environmental issues, political issues, everything, and I think there’s just a lot falling on us and we’re [expletive] tough for going through it.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“[T]he pride in myself and the pride of my work is the biggest one, I think, that resonates with me. Just because I’ve seen what it’s done with my career, with my education…. I’m a manager and I’ve seen the work ethic of some of the older generation, and they say it’s there, but it’s not. A lot of the younger people I’m seeing — fresh, no experience — some of my best workers that I’ve had.”

— Male participant in the Hispanic group

At the same time, many Gen Z respondents expressed gratitude for guidance and support they’d received from their parents and grandparents and hoped to emulate positive values that their elders instilled in them, including a strong work ethic and deep care and concern for their families.

“I think my parents’ generation worked very, very hard and kind of just put their head down, and didn’t complain, and went to work every day, came home, spent time with their family — just repeated for 60 years, whatever. And I really respect that, and I value that and try to emulate that as well.”

– Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“I think, especially for my parents, it would be how diligent they are and how they persevered. They immigrated from Nigeria to the States over 20 years ago, and I feel like the positions they hold now have really inspired me, especially to becoming a doctor and knowing that I can do it, since they achieved the positions they have because of all the hard work they put in…. Whether it’s providing financial support or just encouraging me if I feel like I’m not doing the best I can, just them being in my corner has really helped me.”

– Female participant in the Democratic group

Are Younger People Lazy or Ill-Prepared for the Economy?

Younger People Are Too Lazy

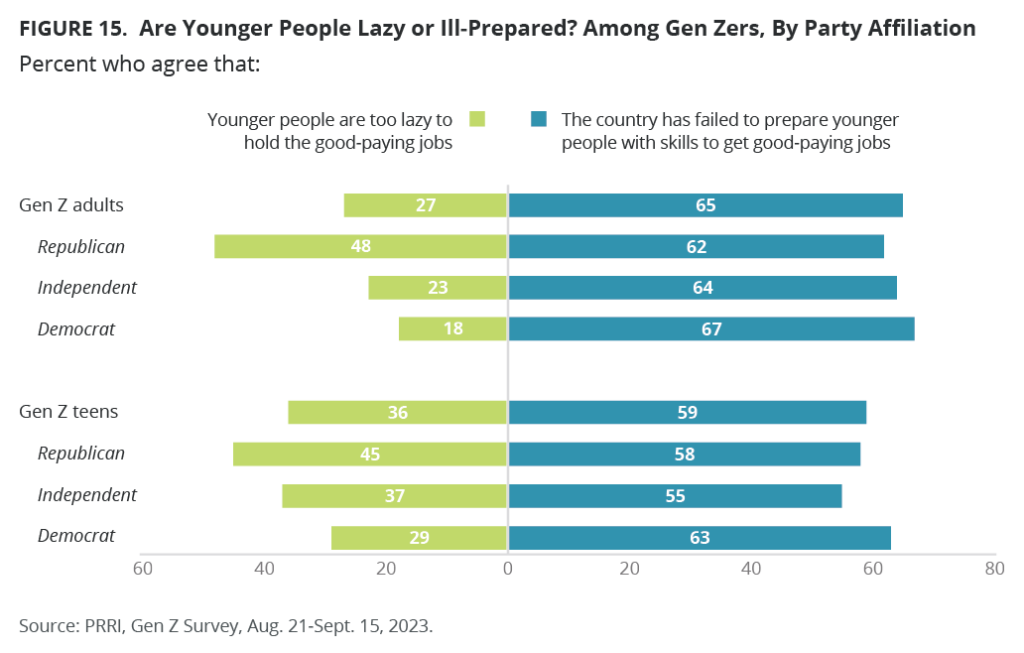

More than one-third of Americans (36%) say that younger people are too lazy to hold good-paying jobs. Nearly three in ten Gen Z adults (27%) and members of the Silent Generation (29%) agree with this statement, compared with 34% of millennials, 37% of baby boomers, and 42% of Gen X.

Among Gen Zers, teens (36%) are more likely than adults (27%) to believe that younger people cannot hold good-paying jobs because they are lazy. This is true among independent teens and adults (37% vs. 23%) and Democratic teens and adults (29% vs. 18%), but not among Republican teens and adults. White teens are more likely than white adults (36% vs. 25%) to hold this belief, as are Gen Z girls compared with Gen Z women (43% vs. 24%).

Among Gen Z adults, Republicans (48%) are more than twice as likely as independents (23%) and Democrats (18%) to believe that younger people are not holding good-paying jobs because they are lazy, but there are no significant differences by race or gender.

Among Gen Z teens, Republicans (45%) are also more likely than Democrats (29%) to believe that younger people are not holding good-paying jobs because they are lazy, but they do not differ from independents (37%). There are no differences by race or gender among Gen Z teens on this question.

The Country Has Failed to Prepare Younger People

The majority of Americans (62%) believe that “The country has failed to prepare younger people with skills to get good-paying jobs.” Americans of all generations are similarly likely to agree with this statement, including 65% of Gen Z adults, 65% of millennials, 61% of Gen X, 58% of baby boomers, and 60% of the Silent Generation.

Gen Z adults (65%) are more likely than Gen Z teens (59%) to believe that “The country has failed to prepare younger people with skills to get good-paying jobs” For both groups, these numbers are similar across party, race, and gender lines.

Focus Group Insights:

Economic Concerns Remain Gen Z’s Biggest Challenge

When asked what issues their generation is focusing on today, participants listed numerous concerns, including a lack of access to reproductive rights and health care generally, challenges to the rights of LGBTQ Americans, racial discrimination in the criminal justice system, rising crime rates, immigration and the crisis at the Southern border, book bans, and the education system. Far and away, however, the issue that dominated conversation among all focus groups was the economy. Gen Zers found common ground on their economic struggles, referencing high unemployment rates, low wages, and rent prices as among the biggest political challenges today.

“[T]he issues we’re having [are] lack of job opportunities, especially jobs that would give us the boost that we can, like, create better lives for ourselves. So just not a lot of opportunities. And especially when you grow up in a certain city, you’re raised in a certain city, but the other transplants are the ones who get the job, it feels like a punch in the face.”

— Female participant in the political independent group

“I used to work as a receptionist in health care, and the amount of things I had to do, and was barely living paycheck to paycheck. It was just not an equal amount of pay for the amount of work…. I have no problem with working, I’m a workaholic. I just want to be accurately paid for what I’m doing and be able to live off of it.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“I don’t think anyone should have to work 60 hours just to afford rent or food or water. And that’s what really kind of keeps me up the most.”

— Male participant in the Hispanic group

Debt was another looming concern identified by Gen Z adults in nearly all of the focus groups. While a few respondents discussed their personal success with the federal student loan forgiveness program, most Zoomers who had amassed college debt or were in the process of doing so instead believed that student debt was overwhelming and would limit their options to move forward in their lives. Others expressed anxiety about credit card debt as well, seeing little way to move ahead financially in the future.

“I would say it’s kind of a combination of the fact that the payments are coming due again. Like, they were frozen for a couple years, and so a lot of the people that I’m in school with are affected by that…. There’s a student loan whole crisis, a lot of student loan debt at the moment that affects people in my community.”

— Male participant in the white, college-educated group

“My husband and I got married, I was fresh out of college, a teacher, and he was in the Army, and we’ve been living paycheck to paycheck for four years. Even though he’s gotten salary increases — he’s changed jobs, he’s making significantly more money — but we’re not going to be able to own a house for the next two years. We’re in crippling credit card debt, I’m on government assistance trying to put food on the table…. I feel like we’re never going to escape these burdens.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“I was gonna say student loans. I’m a recent graduate and it was on pause for at least a year, and then October 1 it started up again. And I was under the impression that some of it would be forgiven…. Only was under that impression because Joe Biden was pretty — he wanted to get it forgiven, so I kind of forgot about it and then a couple months ago it says, Oh, you’ve still gotta pay them. So it was a rollercoaster of emotions. That’s just one thing I’m facing right now that kinda keeps me up at night.”

— Male participant in the Democratic group

Many Gen Z respondents viewed these economic concerns through the lens of generational change, noting that, compared with their parents or grandparents, it was far harder for them to get ahead and achieve the American dream, whether that means being able to afford housing, college, or other expenses.

“[M]y parents, like, they got a job and a couple years later they would have a two-bedroom, three-bedroom house anywhere in America. Now it’s kind of like you get a job but … like, 80% of Americans with a median salary basically can’t afford the house, and it’s been the highest ever in the history of America. So I think financial stability was much, I wouldn’t say easier, but much more attainable for my parents’ generation than it is today.”

— Male participant in the Democratic group

“I feel like cost of living, like, our generation is getting hit way harder. No offense to generations above us, but I feel like everything is just so much more difficult. I was reading an article that says, like, my generation is more likely to be living at home than to actually be able to get our own place. And that’s so true. I’m back at home because it’s so expensive to even try to live by yourself.”

— Female participant in the white, non-college-educated group

“[D]efinitely for previous generations who were born in the 1950s, 1960s, like, the students loans weren’t for them as it is for our current generation, as the cost of schooling has increased.”

— Female participant in the Democratic group

The Role of Education and Programs to Prepare Young People for the Future

College Is a Smart Investment

Americans are evenly divided on the question of a college education: 48% say that a college education is a smart investment in the future, while 51% say it is more of a gamble that may not pay off in the end. Around half of Gen Z adults (49%), Gen Xers (50%), and baby boomers (51%) say college is a smart investment, compared with 57% of the Silent Generation. Millennials (42%) are the least likely of any generation to say that college is a smart investment, and 57% of millennials say that college is more of a gamble.

Gen Z teens (56%) are more likely than Gen Z adults (49%) to say that college is a smart investment for the future. Majorities of non-white teens (63%) and adults (53%), as well as 60% of Gen Z girls and half of Gen Z women (50%), also agree.

Majorities of both Gen Z Republican adults (57%) and Gen Z Democratic adults (56%), along with 45% of Gen Z independents, believe college remains a smart investment. Majorities of partisan Gen Z teens believe college is a smart investment as well.

Non-white teen Zoomers (63%) are more likely to believe that college is a smart investment than their white counterparts (50%), but there are no significant differences by gender.

College Affirmative Action or Assistance for Poor Students and Student Loan Forgiveness

Most Americans (63%) say programs that help poor students or students of color get admission to selective or prestigious colleges are at least somewhat effective in preparing young people for the future, while around one-third (35%) say they are not very or not at all effective. Similar percentages of millennials (67%) and Gen Z adults (69%) find such programs effective. Around six in ten members of older generations, including 62% of Gen X, 58% of baby boomers, and 63% of the Silent Generation, believe these programs are effective.

Similarly, six in ten Americans (60%) say a program to forgive up to $10,000 in student loans for people making less than $125,000 per year would be very or somewhat effective in preparing young people for the future, while 38% say such programs are not very effective or not at all effective. Younger generations are more likely than older generations to believe loan-forgiveness programs are effective, with 75% of Gen Z adults, 67% of millennials, and 60% of Gen Xers in agreement, compared with 50% of baby boomers and 51% of the Silent Generation.

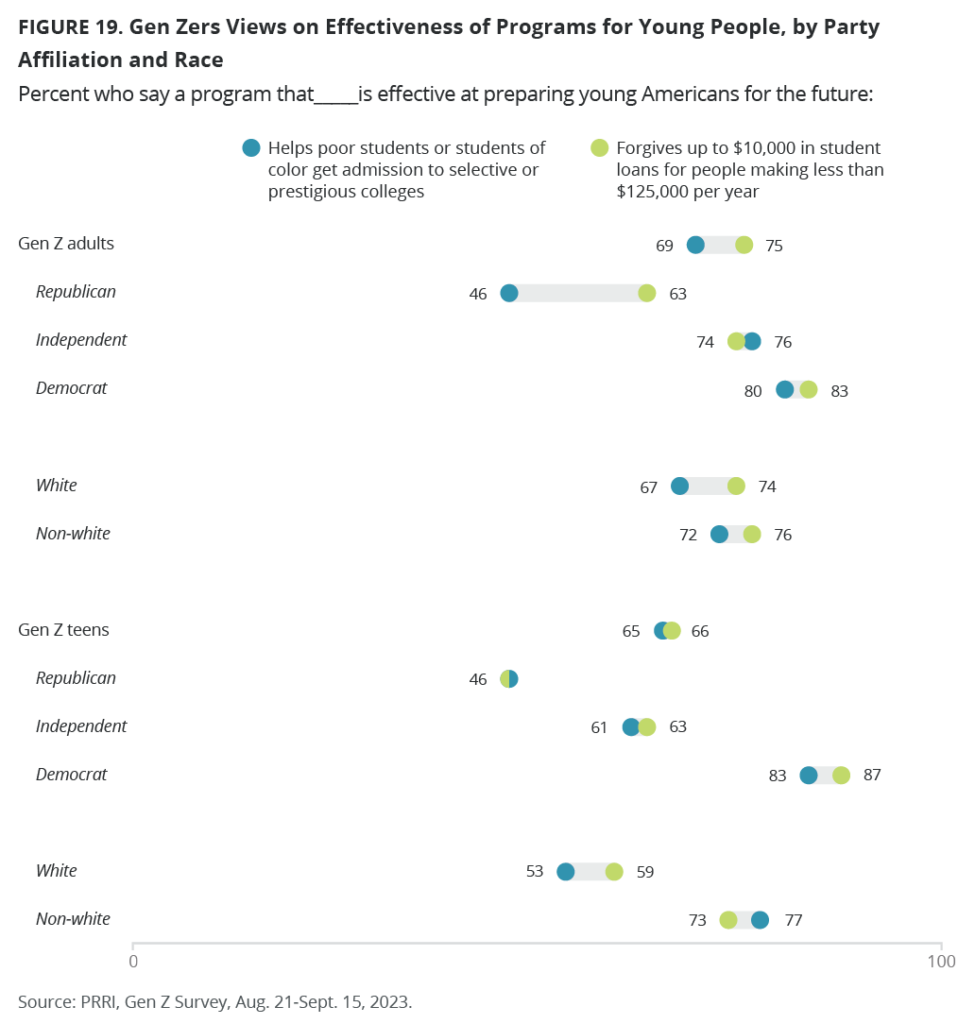

Majorities of Gen Z adults (69%) and teens (65%) believe in the effectiveness of programs that would help poor students or students of color get admission to selective or prestigious colleges. Similarly, Generation Zers tend to believe that forgiving student loans would help prepare young people for the future, with 75% of adult Gen Zers and 66% of teen Gen Zers holding this view.

Partisanship clearly colors attitudes about both sets of policies. Among Gen Z partisans, vast majorities of both adult and teen Democrats (80% and 83%, respectively) and independents (76% and 61%, respectively) support both programs. By contrast, while less than half of Gen Z Republican adults and teens (both 46%) support programs that help poor students or students of color get admission to selective or prestigious colleges, the majority of Gen Z Republican adults (63%) support forgiving student debt, compared with only 46% of Republican teens.

While there are no differences by gender among Gen Zers on these questions, there are differences along racial lines. A strong majority of non-white Gen Z teens express support for programs that help students get admission to prestigious colleges (77%) and for programs that forgive student debt (73%), while support is lower among white teens (53% and 59%, respectively).

Providing Money for Trade or Technical School

Overall, Americans have positive views of programs aimed at preparing young Americans for the future. The vast majority of Americans (88%) say providing money for students to attend two years of trade or technical school would be very or somewhat effective in preparing young people for the future. This is true across all generations, with 83% of Gen Z adults, 87% of millennials, 90% of Gen Xers, 88% of baby boomers, and 92% of the Silent Generation supporting these programs. Only 10% of Americans say such programs would be not very effective or not at all effective.

Among Gen Zers, more than eight in ten adults (83%) and teens (89%) believe in the effectiveness of programs that provide money for trade or technical school.

Among Gen Z adults, around nine in ten Democrats (94%) and independents (86%) believe that providing money for trade or technical school would be very or somewhat effective in preparing young people for the future. There is a drop in support among adult Gen Z Republicans (71%). Partisan differences among Gen Z teens are not significant on this measure.

Training for Political and Community Work

Nearly eight in ten Americans (79%) say an effective way to prepare young people for the future would be to provide training to help them understand the political system or solve problems in their communities. Just two in ten Americans (20%) say this type of program would be not very effective or not at all effective. Vast majorities of Gen Z adults (83%) and older generations, including 80% of Millennials, 78% of Gen X, 77% of Baby Boomers, and 81% of the Silent Generation, say such training would be effective.

Gen Z adults (83%) are more likely than Gen Z teens (74%) to support programs that provide training for political and community work. Among Gen Z adults, nine in ten Democrats (89%) and independents (85%) believe such programs would be effective, compared with seven in ten Gen Z Republican adults (74%).

Among teen Gen Z partisans, 87% of Democrats, 71% of independents, and 67% of Republicans believe in the effectiveness of programs that provide training for young people to help them understand the political system and solve problems in their communities.

Money for Community Service

Nearly three in four Americans (73%) believe a program providing money for high school graduates to work in community service before starting a job or going to college would be a very or somewhat effective way to prepare young people for the future, compared with one quarter of Americans (25%) who say such a program would be not very effective or not at all effective. More than seven in ten Gen Z adults (73%), millennials (73%), baby boomers (74%), Gen Xers (72%) and members of the Silent Generation (75%) believe providing students with money to work in community service would be effective.

Solid majorities of Gen Z adults (73%) and teens (76%) believe in the effectiveness of such programs. Among Gen Z adults, Democrats (82%) are generally more likely than Republicans (69%) and independents (66%) to believe that a program providing money for high school graduates to work in community service would be effective. Similarly, among Gen Z teens, 83% of Democrats, 75% of independents, and 66% of Republicans believe such a program would be effective.

Community and Political Institutional Trust

Forming Connections

PRRI asked how Americans make meaningful friendships and connections throughout their lives. Close to four in ten Americans say they make friends by participating in a religiously focused activity (38%), playing sports (32%), engaging in social media (32%), or participating in a political or advocacy group (30%). Meanwhile, around two in ten Americans (22%) say playing video games is either somewhat or very important for making meaningful friendships and connections.

Millennials (32%) are notably less likely than Gen Z adults (39%), Gen Xers (39%), baby boomers (41%), and members of the Silent Generation (42%) to find meaningful relationships through religious activities, but they do not differ meaningfully from Gen Z adults (32%) and Gen Xers (28%) when it comes to finding political or advocacy group participation to be a source of connection. About one-third of baby boomers (32%) and the Silent Generation (33%) also find connections through political and advocacy groups. Gen Z adults are more likely than other generations to find friendships and connections through organized sports (42% vs. 37% of millennials, 34% of Gen X, 25% of baby boomers, and 20% of the Silent Generation), video games (48% vs. 33% of millennials, 15% of Gen X, 8% of baby boomers, and 8% of the Silent Generation), and social media (52% vs. 36% of millennials, 29% of Gen X, 24% of baby boomers, and 18% of the Silent Generation).

Given that they are still in high school, it is not surprising to find that Gen Z teens are substantially more likely than Gen Z adults to say they find meaningful connections by playing organized sports (58% vs. 42%, respectively). Gen Z teens are also more likely to find meaningful connections through playing video games (58% vs. 48%, respectively), and participating in religiously focused activities (44% vs. 39%, respectively). However, Gen Z adults and teens are about equally likely to find connections through social media (48% vs. 52%, respectively). By contrast, Gen Z adults (32%) are nearly ten percentage points more likely than Gen Z teens (23%) to find political or advocacy groups important for making meaningful connections.

Among Gen Z adults, Republicans (61%) are more likely than independents (34%) and Democrats (31%) to say they find participating in religiously focused activities important for making connections. Democrats (65%), meanwhile, are more likely than Republicans (48%) and independents (42%) to say engaging in social media is important. Around half of Republicans (51%), 45% of independents, and 38% of Democrats say that participating in organized sports is important for making connections. About four in ten Democrats (38%) and about three in ten independents (29%) and Republicans (27%) believe participating in a political or advocacy group is important. Half of Democrats and independents (50% each) and 44% of Republicans say playing video games is important for making connections.

There is little difference between white and non-white Gen Z adults in how they find meaningful connections. The only significant difference by gender appears on the question of video games: Gen Z men (62%) are roughly twice as likely as Gen Z women (35%) to find connections through video games.

Among Gen Z teens, Republicans (67%) are more likely than independents (45%) and Democrats (27%) to say religiously based activities are important for making meaningful connections. More than half of Democrats (54%) and independents (51%) and 43% of Republicans say that engaging in social media is important. Majorities of each Gen Z teen partisan group say they find connections through organized sports (65% of Republicans, 62% of independents, and 54% of Democrats) or playing video games (62% of independents, 57% of Democrats, and 50% of Republicans). Less than three in ten of each group (26% of Democrats, 25% of independents, and 20% of Republicans) say participating in a political or advocacy group is important.

Similar to their adult counterparts, there are no significant differences by race among teens, but Gen Z boys (74%) are significantly more likely than girls (40%) to say playing video games is important for making connections.

Focus Group Insights:

Making Meaningful Social Connections

Gen Z adults were asked about how they make social connections with others and how their ways of connecting may differ from what previous generations did. Some Gen Zers expressed the view that generations before them had stronger bonds and more trust in their neighbors, likely because face-to-face interactions were more common in a world without social media. Likewise, some participants said social media’s negative attributes, such as anonymity and a propensity for negative, destructive discourse, present a challenge for young people hoping to form meaningful connections with other individuals.

“For my parents, I know for them … like, they all grew up in the same area … so they knew everybody. Everybody was close, everybody knew their neighbors, and their neighbors were like second parents. It was like community, like community was real.”

— Male participant in the LGBTQ group

“I think meeting people and being more social and, like, the dating scene and everything, was a bit more straightforward [for my parents.]. There wasn’t all these online things. People didn’t feel like there were so many options or opportunities, but also, like, lack of face-to-face interaction. It just seemed more simplified and, like, easy to meet people in person.”

— Female participant in the political independent group

“I think it’s true … how people are able to insult others, it’s so much easier to do it over the internet, because you can just hide behind a username and a fake photo…. When you’re in person, you have to face the emotions of people rather than just their words. In person, you can be like — you can express your emotions so much better. Whereas, even just, like, texting, you can take things so much out of context just because you can’t see facial expressions. I feel like it just has taken away that ability to say something clearly.”

— Female participant in the Republican group

While most Gen Zers believed that older generations had stronger community connections, others noted that a lack of access to social media potentially limited the connections older generations could make outside their neighborhoods as they were growing up — in essence, limiting their worldviews. By contrast, many Zoomers care deeply about issues happening nationally and globally, in part because they can form meaningful connections and understanding with people regardless of where they live.

“I was gonna say earlier, I think something very unique about our generation is that we care so much. I think our parents’ generations and the generations before them, like, if it wasn’t in their immediate community, it didn’t really affect them.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“I think the older generations, they didn’t know what was going on around the world besides what they saw. So they didn’t know what was going in Israel, what was going on in Venezuela, anywhere else. Like, they only knew what was happening in their hometown because they didn’t have social media. So it’s kind of weird that the generation that has access to so many things, and we get to see the lives of so many people that we will not meet, for us to not care, because we do care.”

— Female participant in the Republican group

Political Institutional Trust

The Police

Seven in ten Americans (70%) say they have some or a great deal of trust in the police, while 29% have little or no trust at all. Gen Z adults (53%) and millennials (57%) are more closely aligned than other generations in their trust of police. Strong majorities of Gen Xers (74%), baby boomers (85%), and the Silent Generation (89%) trust the police.

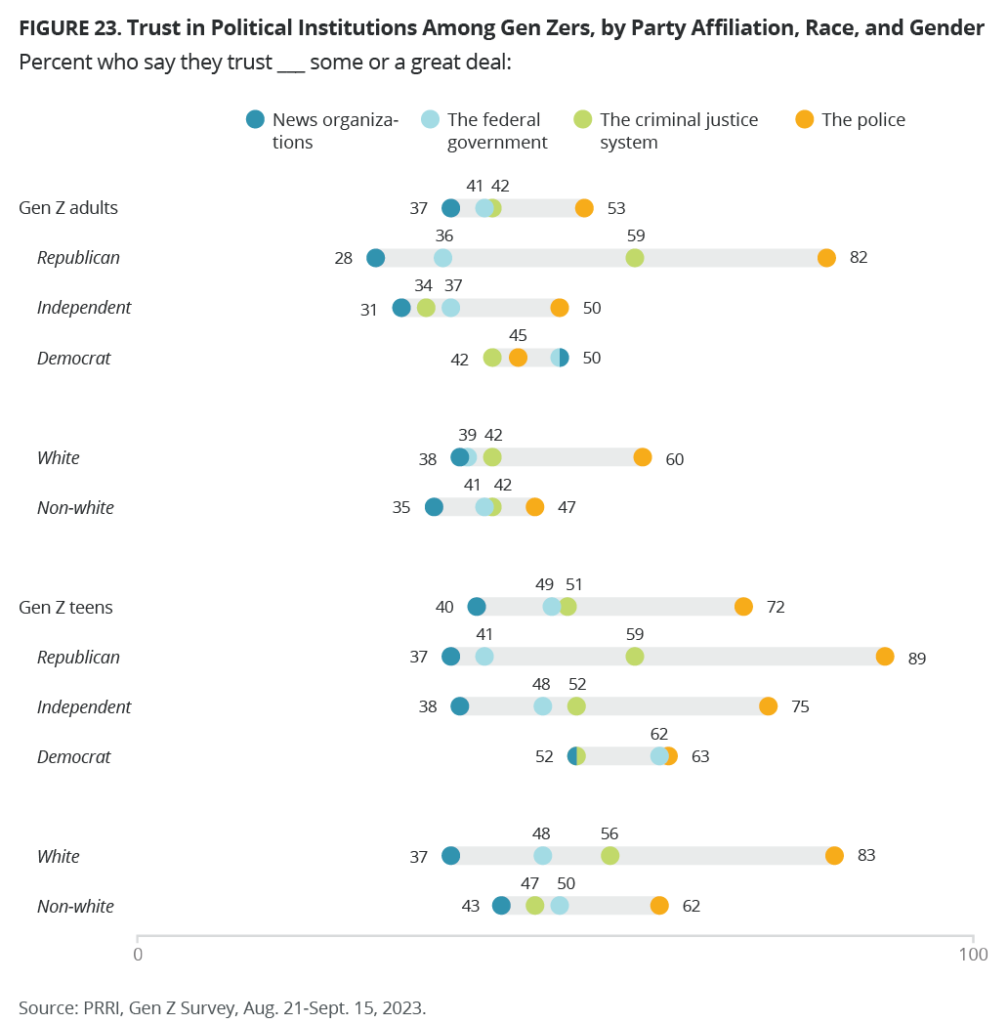

Looking at Gen Z specifically, Gen Z teens (72%) are more likely than Gen Z adults (53%) to trust the police. Among Gen Z adults, Republicans (82%) are much more likely than independents (50%) and Democrats (45%) to say they have at least some trust in the police.

While there are no significant differences by gender on this question, there are differences by race. Six in ten white Gen Z adults (60%) say they trust the police, compared with less than half of non-white Gen Z adults (47%).

The vast majority of Gen Z teen Republicans (89%) say they trust the police some or a great deal, compared with 75% of independents and 63% of Democrats. Majorities of both white and non-white Gen Z teens say they trust the police (83% vs. 62%), although this gap is more pronounced among teens than among Gen Z adults.

The Criminal Justice System

More than half of Americans (52%) have at least some trust in the criminal justice system, but only 9% have a great deal of trust. Gen Z adults (42%) and millennials (43%) are less likely than Gen Xers (56%), baby boomers (60%), and members of the Silent Generation (61%) to have some or a great deal of trust in the criminal justice system.

Gen Z teens are more likely than Gen Z adults to trust the criminal justice system (51% vs. 42%). Among Gen Z adults, Republicans (59%) are more likely to say they have some or a great deal of trust in the criminal justice system than Democrats (42%) and independents (34%). Among both white and non-white adults, as well as Gen Z women and Gen Z men, roughly four in ten trust the criminal justice system.

Among Gen Z teens, slim majorities of Republicans (59%), independents (52%), and Democrats (52%) say they trust the criminal justice system. White teens (56%) are more likely than non-white teens (47%) to trust the criminal justice system, but boys and girls do not differ.

The Federal Government

Americans are evenly divided on their trust in the federal government (49% say they trust the government, and 50% say they have little or no trust). Majorities of older generations, including 51% of Gen Xers, 56% of baby boomers, and 61% of the Silent Generation, say they trust the federal government at least some, compared with less than half of younger generations, including 41% of Gen Z adults and 44% of millennials.

Gen Z adults (41%) are less likely than Gen Z teens (49%) to trust the federal government. Among Gen Z adults, half of Democrats (50%) and nearly four in ten independents (37%) and Republicans (36%) say they have some or a great deal of trust in the federal government.

Among Gen Z teens, the majority of Democrats (62%), half of independents (48%), and about four in ten Republicans (41%) say they have at least some trust in the federal government.

News Organizations

More than four in ten Americans (43%) have some or a great deal of trust in news organizations, compared with 56% who have little or no trust at all. The Silent Generation (58%) is the only generation in which a majority of members say they have some or a great deal of trust in news organizations, compared with 37% of Gen Z adults, 36% of millennials, 45% of Gen Xers, and 49% of baby boomers.

Among Gen Z, four in ten of both teens (40%) and adults (37%) say they trust news organizations. Among Gen Z adults, half of Democrats (50%) say they trust news organizations some or a great deal, compared with 31% of independents and 28% of Republicans.

Similar to their adult counterparts, teen Gen Z Democrats (52%) are more likely than independents (38%) and Republicans (37%) to say they trust news organizations.

Focus Group Insights:

Gen Z’s Lack of Trust in Institutions

We asked Gen Z adults about their level of trust in political and community institutions. Most participants expressed little faith in the federal government or elected officials in Washington. Many Gen Z adults believed that elected officials put the needs of the wealthy or corporations ahead of average Americans, while others believed that political polarization led to gridlock and made it impossible for the federal government to solve our most basic problems. Others expressed concern that federal office holders, because they are too old and lack diversity, are out of touch with the needs of most Americans, particularly younger adults.

“I think what happens is politicians or people, they try to make it seem like they’re doing what’s best for you, and then people feed into that to get them voted on. Then, when they get into office, they do what’s best for them and not what’s best for everybody else.”

— Male participant in the Black group

“I feel like the younger generation, like around our age, can’t really relate to politicians nowadays, just because they’re a lot older and they don’t have the same life outlook as we do.”

— Male participant in the Republican group

“[O]f course there are a lot of individual issues, but none of them can really be fixed with gridlock in Congress, with very polarizing candidates, geriatric candidates, people that aren’t really voting in our collective interest.”

— Male participant in the Democratic group

Although focus group participants had little positive to say about the federal government, several said they were grateful for assistance they received from the federal government during COVID, in the form of stimulus checks and the suspension of student loan payments. Some Gen Zers also recognized that their local and state governments were sometimes successful, particularly when it came to issues such as infrastructure, libraries, parks, and social programs.

“With state and local [government], I think that maybe some of the public spaces might be good. I think like some of the roads and things like that, I think that would be something that would be good.”

— Male participant in the Black group

“My city also has a good library system, and we also have lots of local parks, which I think is really important.”

— Female participant in the LGBTQ group

Most Gen Zers expressed a deep lack of trust in the news media, with some noting that they have struggled to find nonpartisan views on current events in the media, making it a challenge to engage in politics more broadly. Because many Gen Z adults lack trust in mainstream news organizations, they often expressed feeling it was necessary to validate the news they heard through research and an examination of multiple different sources. Instead of turning to major news outlets, Zoomers discussed following independent journalists to keep up with current events.

“I think if the news sources that are practically just partisan propaganda, then you’re not really getting news that is worthwhile to digest in the first place.”

— Male participant in the white, non-college-educated group

“[I] find myself frustrated because I search for truth and look for facts, and between conspiracy theorists and right versus left it’s hard to read through the biases and determine what the truth is. So I don’t feel inclined to get involved at the moment, because I struggle to know what’s actually happening.”

— Female participant in the white, college-educated group

“I do think with social media and having our phones at our fingertips, like, it is easier to kind of find information for yourself and form your own opinions rather than depending on what cable news is saying, or to find, like, independent news people that you like and that you can trust.”

— Female participant in the LGBTQ group

“Typically, I look for independent reporters, people that aren’t paid by Fox or paid by CNN or paid by anyone, they’re just doing it for themselves, for the passion of revealing the truth. I think those are really, really important people. I think that mainstream media can still be useful and important to get general details on general events, but that specific details, I think that those type of mainstream media companies, left or right, they’ll try to misconstrue or purposely put the details in a different light to kind of misconstrue the truth.”

— Male participant in the Republican group

How Does Gen Z Engage with Politics?

Views on Voting

Vast majorities of Americans say that the following propositions about voting do not really describe or do not at all describe their views: “Voting is too difficult to understand for people like me” (90%); “The voting age should be lowered to sixteen” (88%); “The voting age should be raised to 25” (86%); “Voting is too difficult to access for people in my community” (86%). This is true across all demographics, including age, race, gender, and religious tradition, and across partisanship lines and levels of trust in media.

The only statement that a majority of Americans agreed with is that voting is the most effective way to create change in America, with 69% saying it completely or mostly describes their views well. However, Gen Z adults (58%) and Millennials (60%) are significantly less likely than Gen Xers (70%), Boomers (80%), and members of the Silent Generation (85%) to agree that voting is the most effective way to create change in America.

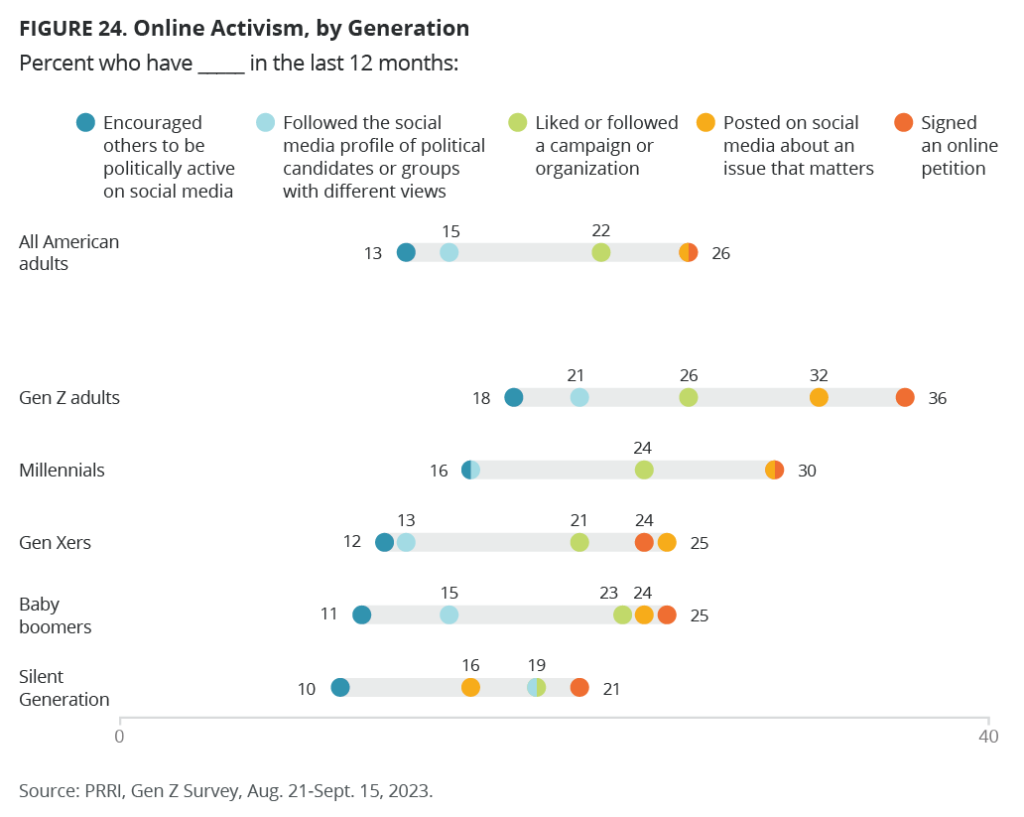

Online Activism

About one in four Americans say they have signed an online petition in the past 12 months (26%), posted on social media about an issue that matters to them (26%), or liked or followed a campaign or organization online (22%). Fewer Americans have followed the social media profile of someone whose views on political candidates or groups are different from their own (15%) or encouraged others to be politically active on social media (13%).

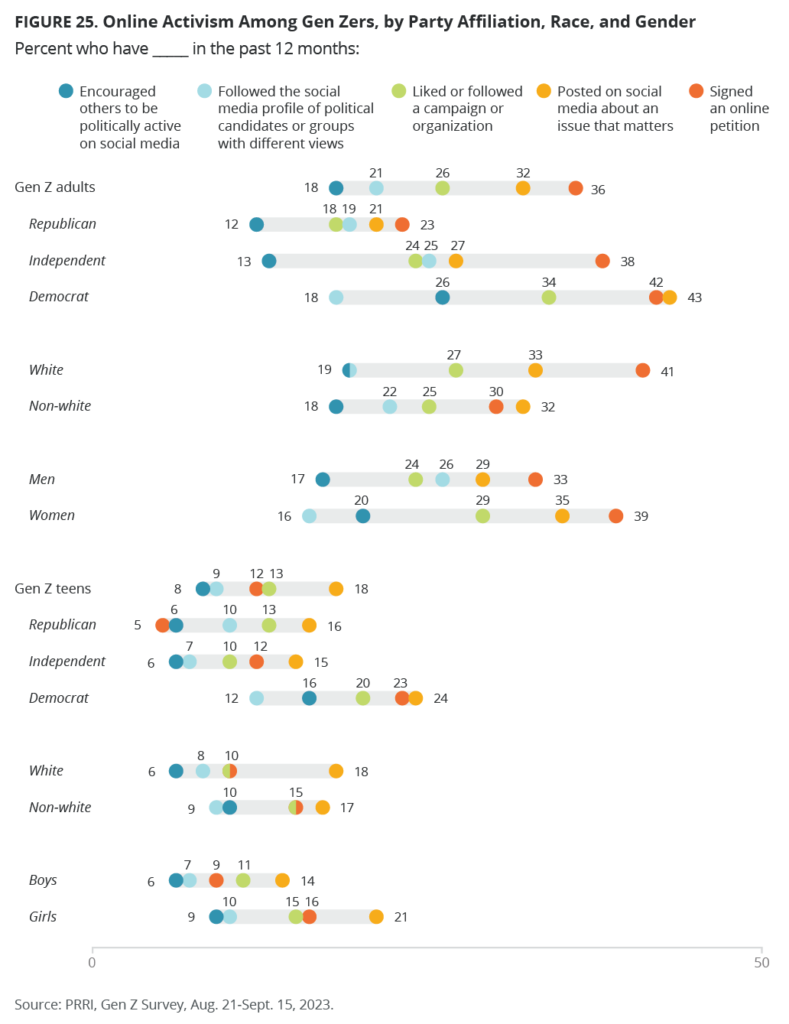

Gen Z adults are notably more likely than older generations to have signed an online petition (36% vs. 30% or less of older generations) or to have followed the social media profile of someone with different views (21% vs. 16% or less). Gen Z adults are also more likely than older generations (with the exception of millennials) to have posted on social media about an issue that matters to them (32% vs. 25% or less of Gen Xers and older generations) or encouraged others to be politically active on social media (18% vs. 12% or less of Gen Xers and older generations). However, Gen Z adults do not differ much from older generations — with the exception of the Silent Generation (19%) — when they say they liked or followed a campaign or organization online (26%).

Focus Group Insights:

How Gen Z Engages in Politics

Voting was the most common form of political participation undertaken by Gen Z focus group participants. While voting was easy for some participants, others noted that getting access to the ballot could be challenging, either because they were in college or because they faced long lines in their home communities or had difficulty taking time off from work to vote. Other Gen Zers offered suggestions on how to make voting more accessible. Still others, however, opted out of voting entirely, unconvinced that their votes made much of a difference in determining policy or political outcomes.

“[I]n the poorer communities … they’re not able to go out and vote because they’re working so much. Or disabled people not having that access to vote … that’s going to be a common trend that we see again this year, or next year…. I grew up in Boston, in a very minority community, and seeing how hard it was to vote — the lines were horribly long — to residing now in a very dominant white community, the process of voting [is] just in and out.”

— Female participant in the Black group

“[A] lot of people have to, like, leave their job early [to vote] or whatnot, and it’s not a national holiday. So the incentive on that front could be, Oh, just make it a national holiday or have some sort of financial incentive to participate.”

— Male participant in the Democratic group

“I think that our votes actually don’t necessarily matter. I think the government has its own agenda and I think it’s going to basically do anything to carry out that agenda.”

— Female participant in the white, non-college-educated group

Some Gen Zers said they often use social media to discuss politics, to learn more about politics, and to try to raise awareness about political issues among their friends. Others, however, were wary about online political engagement, worried that posting on social media raised privacy concerns or that they would face negative feedback and criticism for their political views.

“I do post on my Instagram story sometimes. As much as it does nothing, I try to educate people, if anyone even cares. I try to do that.”

— Female participant in the white, non-college-educated group

“[O]ne thing that caught my eye [on social media] was, like, the blackout day, which is in like June and basically it’s just one day where every African American just does their best to not spend money.… [With] how much African Americans put into the economy of the United States, it would affect them, and then they would notice that, Wow, African Americans are here to actually function, so why are we treating them the way we do?”

— Male participant in the Black group

“I try to go through social media [to discuss politics], but it’s so difficult with my family. Like, they hate having me on social media, and I wish I could just block them. But, anyway, yeah, I do think there’s always more to be done. Yeah, and it’s kind of frustrating when my friends don’t care. They don’t care about what’s going on around them or, like, local and national issues and what’s in the news.”

— Male participant in the white, non-college-educated group

“I think a big issue now, especially with, like, how online everybody is, a big issue is doxing. I think just spreading, like, somebody’s personal information online is just very dangerous, and, I don’t know, I’m hesitant.”

— Male participant in the Hispanic group

Other Gen Zers acknowledged that there are real limits to using social media as a primary form of political involvement, and instead made the case that face-to-face organizing would be a more effective way to achieve political change in the long run. Several Gen Zers had attended protest marches in the past, particularly marches for Black Lives Matters; others said they avoided involvement in mass protests because they thought that such protests were unsafe or ultimately ineffective. Other participants indicated that they donated money to political causes or were active in volunteering in their communities.

“So, I think that, ironically, in this sort of age of mass communication, one of the most effective things you can do is to get a group of very socially coherent, well-organized people and just go out into the street, occupy a sidewalk or some other place of public demonstration, perhaps a courthouse.… [J]ust to make a physical presence with a clear and concise and informed message with a group of people….”

— Male participant in the white, non-college-educated group

“I live in the South — I live in Georgia. I did see a lot of … Stop Cop City protests going around in the state, and now all over the country, which is really, like, nice to see. I did see, like, a lot of people our age canvassing … all over the state. I did see a voice in our generation, which I feel, like, was really exciting, really inspiring to see.”

— Female participant in the LGBTQ group

“I feel like nowadays people think, like, violence and destroying property is going to get the point across. What point is that getting across other than you are an idiot? …[E]specially, like, the George Floyd and all that, Black Lives Matter, it got people’s attention, but I just don’t think it was the right way. Just being destructive, it finally got everyone to listen, but I don’t agree with how it had to happen.”

— Female participant in the white, non-college-educated group