The Rise of the Unaffiliated

America’s Largest “Religious” Group

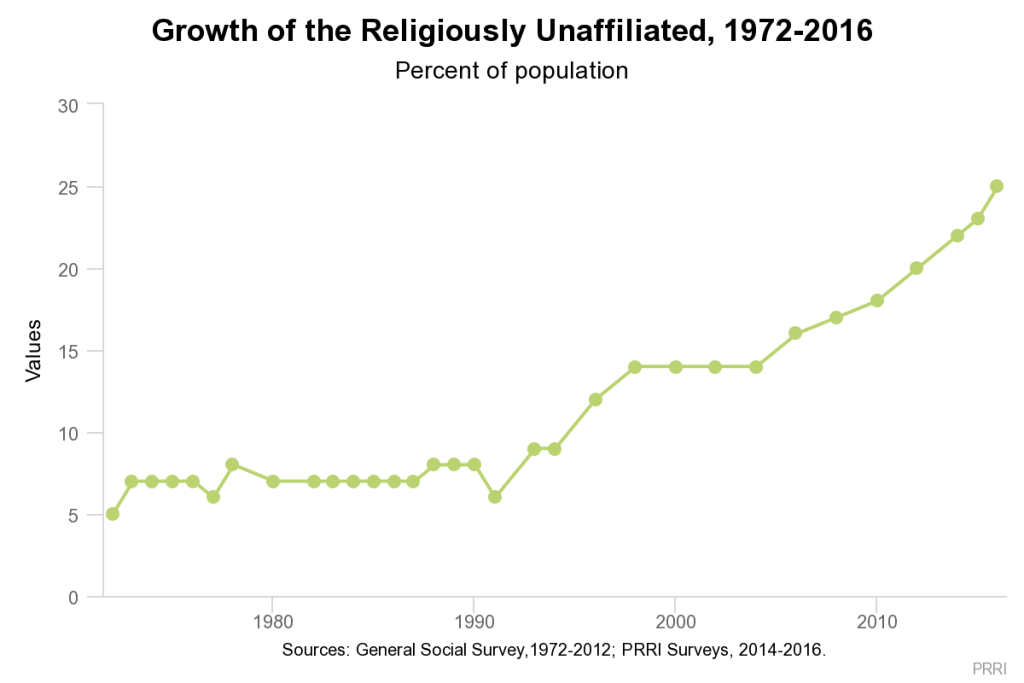

The American religious landscape has undergone substantial changes in recent years. However, one of the most consequential shifts in American religion has been the rise of religiously unaffiliated Americans. This trend emerged in the early 1990s. In 1991, only six percent of Americans identified their religious affiliation as “none,” and that number had not moved much since the early 1970s. By the end of the 1990s, 14% of the public claimed no religious affiliation. The rate of religious change accelerated further during the late 2000s and early 2010s, reaching 20% by 2012. Today, one-quarter (25%) of Americans claim no formal religious identity, making this group the single largest “religious group” in the U.S.

The Decline of Religious Affiliation Among Young Adults

The Decline of Religious Affiliation Among Young Adults

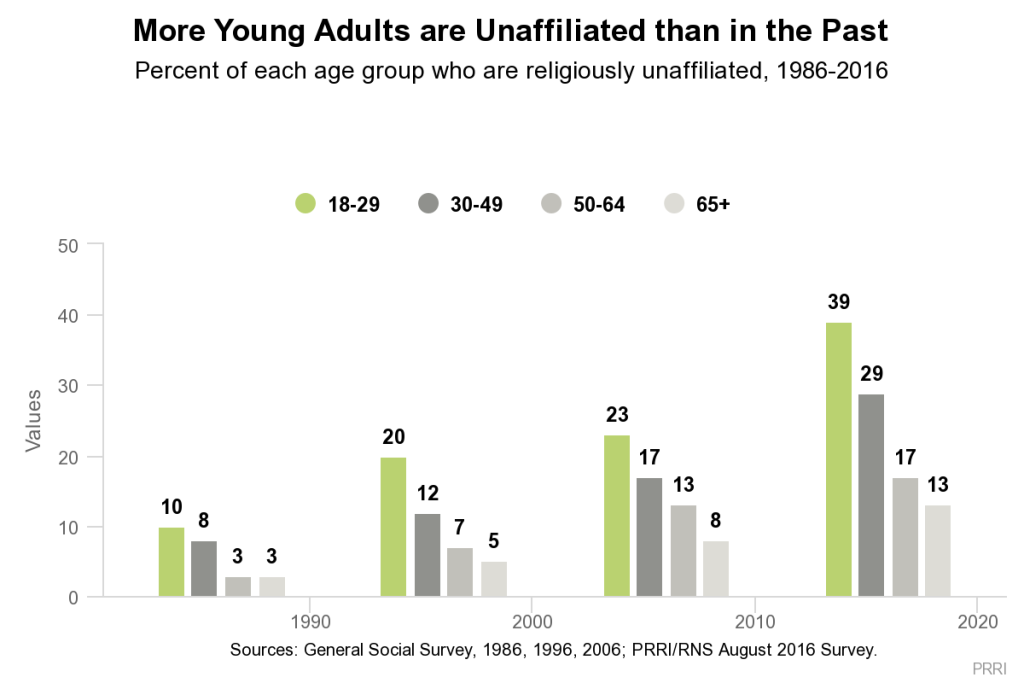

Today, nearly four in ten (39%) young adults (ages 18-29) are religiously unaffiliated—three times the unaffiliated rate (13%) among seniors (ages 65 and older). While previous generations were also more likely to be religiously unaffiliated in their twenties, young adults today are nearly four times as likely as young adults a generation ago to identify as religiously unaffiliated. In 1986, for example, only 10% of young adults claimed no religious affiliation.

Among young adults, the religiously unaffiliated dwarf the percentages of other religious identifications: Catholic (15%), white evangelical Protestant (9%), white mainline Protestant (8%), black Protestant (7%), other non-white Protestants (11%), and affiliation with a non-Christian religion (7%).

The age gap has also widened over the past several decades. Ten years ago, each age cohort was only somewhat more likely to be unaffiliated than the one preceding it. Today, there are only modest differences between middle-aged Americans (age 50 – 64) and seniors, but there is a substantial gap between Americans over the age of 50 (15%) and those under the age of 50 (33%).

Religious Switching

Religious Switching

The growth of the unaffiliated has been fed by an exodus of those who grew up with a religious identity. Only nine percent of Americans report being raised in a non-religious household. And while younger adults are more likely to report growing up without a religious identity than seniors (13% vs. 4%, respectively), the vast majority of unaffiliated Americans formerly identified with a particular religion.

No religious group has benefitted more from religious switching than the unaffiliated. Nearly one in five (19%) Americans switched from their childhood religious identity to become unaffiliated as adults, and relatively few (3%) Americans who were raised unaffiliated are joining a religious tradition. This dynamic has resulted in a dramatic net gain—16 percentage points—for the religiously unaffiliated.

While non-white Protestants and non-Christian religious groups have remained fairly stable, white Protestants and Catholics have all experienced declines, with Catholics suffering the largest decline among major religious groups: a 10-percentage point loss overall. Nearly one-third (31%) of Americans report being raised in a Catholic household, but only about one in five (21%) Americans identify as Catholic currently. Thirteen percent of Americans report being former Catholics, and roughly 2% of Americans have left their religious tradition to join the Church. White evangelical Protestants and white mainline Protestants are also witnessing negative growth, but to a much more modest degree (-2 percentage points and -5 percentage points, respectively).

Rising Retention Rates among the Unaffiliated

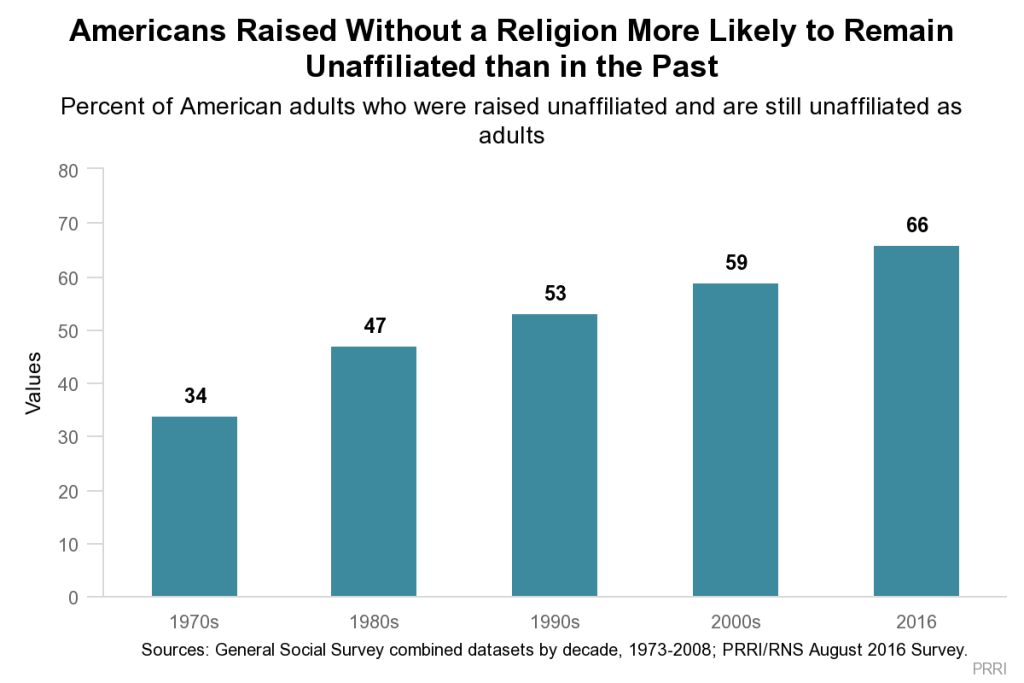

Not every religious community is equally successful in keeping members in the fold, and historically, Americans who were raised unaffiliated were among the most likely to switch their religious identity in adulthood. In the 1970s, only about one-third (34%) of Americans who were raised in religiously unaffiliated households were still unaffiliated as adults. By the 1990s, slightly more than half (53%) of Americans who were unaffiliated in childhood retained their religious identity in adulthood. Today, about two-thirds (66%) of Americans who report being raised outside a formal religious tradition remain unaffiliated as adults.

One important reason why the unaffiliated are experiencing rising retention rates is because younger Americans raised in nonreligious homes are less apt to join a religious tradition or denomination than young adults in previous eras. About three-quarters (74%) of Americans under the age of 50 who were raised nonreligious have maintained their lack of religious identity in adulthood. In contrast, only about half (49%) of Americans age 50 or older who were raised unaffiliated still identify that way.

Why Are Americans Leaving Religion?

Age of Disaffiliation

Most Americans who leave their childhood religious identity to become unaffiliated generally do so before they reach their 18th birthday. More than six in ten (62%) religiously unaffiliated Americans who were raised in a religion say they abandoned their childhood religion before they turned 18. About three in ten (28%) say they were between the ages of 18 and 29. Only five percent say they stopped identifying with their childhood religion between the ages of 30 and 49, and just two percent say age 50 or older.

Causes of Disaffiliation

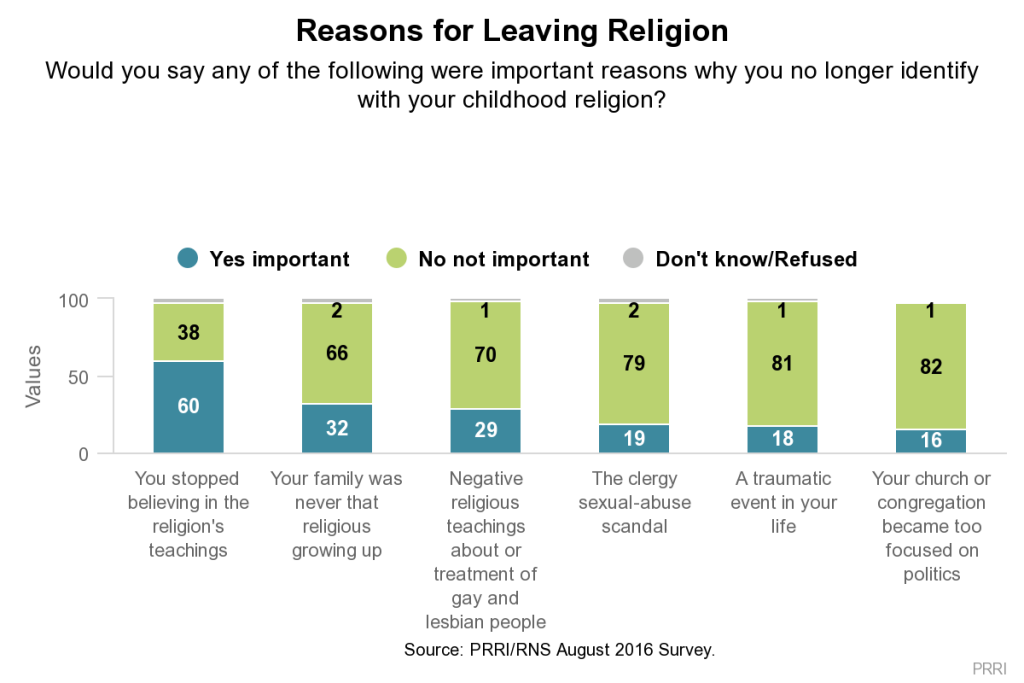

The reasons Americans leave their childhood religion are varied, but a lack of belief in teaching of religion was the most commonly cited reason for disaffiliation. Among the reasons Americans identified as important motivations in leaving their childhood religion are: they stopped believing in the religion’s teachings (60%), their family was never that religious when they were growing up (32%), and their experience of negative religious teachings about or treatment of gay and lesbian people (29%).

Fewer than one in five Americans who left their childhood religion point to the clergy sexual-abuse scandal (19%), a traumatic event in their life (18%), or their congregation becoming too focused on politics (16%) as an important reason for disaffiliating.

Among those who left their childhood religion, women are twice as likely as men to say negative religious teachings about or treatment of gay and lesbian individuals was a major reason they chose to leave their religion (40% vs. 20%, respectively). Women are also about twice as likely as men to cite the clergy sexual-abuse scandal as an important reason they left their childhood faith (26% vs. 13%, respectively).

Young adults (age 18 to 29) who left their childhood religion are about three times more likely than seniors (age 65 and older) to say negative religious teachings about and treatment of the gay and lesbian community was a primary reason for leaving their childhood faith (39% vs 12%, respectively). Young adults are also more likely than seniors to say being raised in a family that was not that religious was a major reason they no longer affiliate with a religion (36% vs. 23%, respectively).

Notably, those who were raised Catholic are more likely than those raised in any other religion to cite negative religious treatment of gay and lesbian people (39% vs. 29%, respectively) and the clergy sexual-abuse scandal (32% vs. 19%, respectively) as primary reasons they left the Church.

Notably, those who were raised Catholic are more likely than those raised in any other religion to cite negative religious treatment of gay and lesbian people (39% vs. 29%, respectively) and the clergy sexual-abuse scandal (32% vs. 19%, respectively) as primary reasons they left the Church.

Most Americans who have left a religious tradition do not identify a particular negative experience or incident as the catalyst. Relatively few Americans who are now unaffiliated report their last experience in a church or house of worship was negative. In fact, more than two-thirds (68%) of unaffiliated Americans say their last time attending a religious service, not including a wedding or funeral service, was primarily positive. Only one in five (20%) unaffiliated Americans say their last visit to a religious congregation was mostly negative.

Family Dynamics and Religious Disaffiliation

Divorce

Previous research has shown that family stability—or instability—can impact the transmission of religious identity. Consistent with this research, the survey finds Americans who were raised by divorced parents are more likely than children whose parents were married during most of their formative years to be religiously unaffiliated (35% vs. 23% respectively).

Rates of religious attendance are also impacted by divorce. Americans who were raised by divorced parents are less likely than children whose parents were married during most of their childhood to report attending religious services at least once per week (21% vs. 34%, respectively). This childhood divorce gap is also evident even among Americans who continue to be religiously affiliated. Roughly three in ten (31%) religious Americans who were brought up by divorced parents say they attend religious services at least once a week, compared to 43% of religious Americans who were raised by married parents.

Religiously Mixed Households

Americans raised in mixed religious households—where parents identified with different religious traditions—are more likely to identify as unaffiliated than those raised in households where parents shared the same faith (31% vs. 22%, respectively).

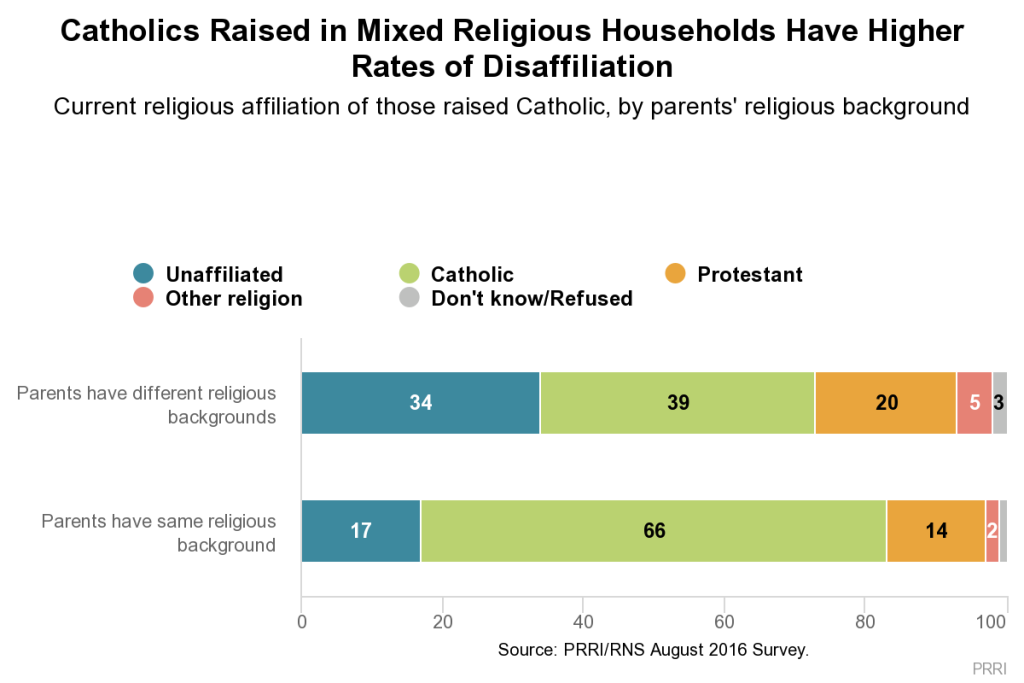

Among those who were raised Catholic, there is a particularly strong correlation between those whose parents were both Catholic and those who had one parent with a different religious identity. Among those who were raised Catholic by parents who did not share the same religious identity, about four in ten (39%) remain Catholic as adults. In contrast, nearly two-thirds (66%) of those raised in Catholic households by parents who were both Catholic remain Catholic as adults.

The Rise of Religiously Unaffiliated Households

The Rise of Religiously Unaffiliated Households

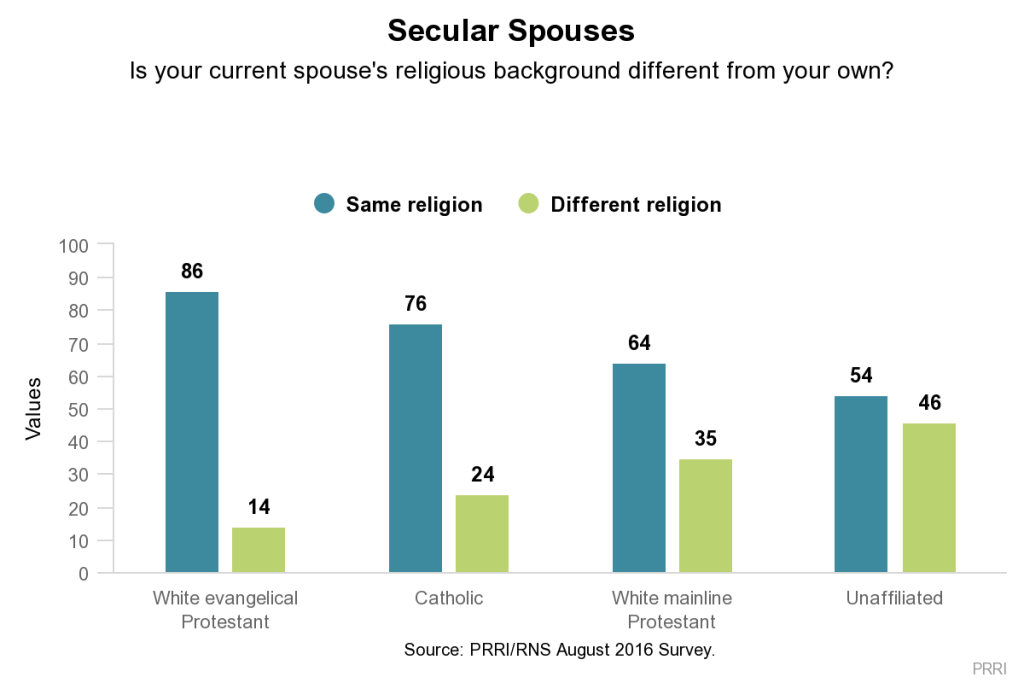

One critical shift that occurred over the past several decades is the increasing likelihood of religiously unaffiliated Americans to form households with religiously likeminded partners. A majority (54%) of unaffiliated Americans who are married today report that their spouse shares the same religious background as they do. A generation earlier, unaffiliated Americans were much more likely to end up with religious spouses. In the 1970s, more than six in ten (63%) unaffiliated Americans who were married reported that their spouse identified with a religious tradition.

Despite the rising rates of homogamy among the unaffiliated, however, they are still less likely to marry someone who shares their religious background than members of other religious groups. For example, 86% of white evangelical Protestants who are married report that their spouse shares their religious background, as do roughly three-quarters (76%) of married Catholics.

Despite the rising rates of homogamy among the unaffiliated, however, they are still less likely to marry someone who shares their religious background than members of other religious groups. For example, 86% of white evangelical Protestants who are married report that their spouse shares their religious background, as do roughly three-quarters (76%) of married Catholics.

Perceptions of Religion and God Among the Religiously Unaffiliated

Perceptions of Organized Religion

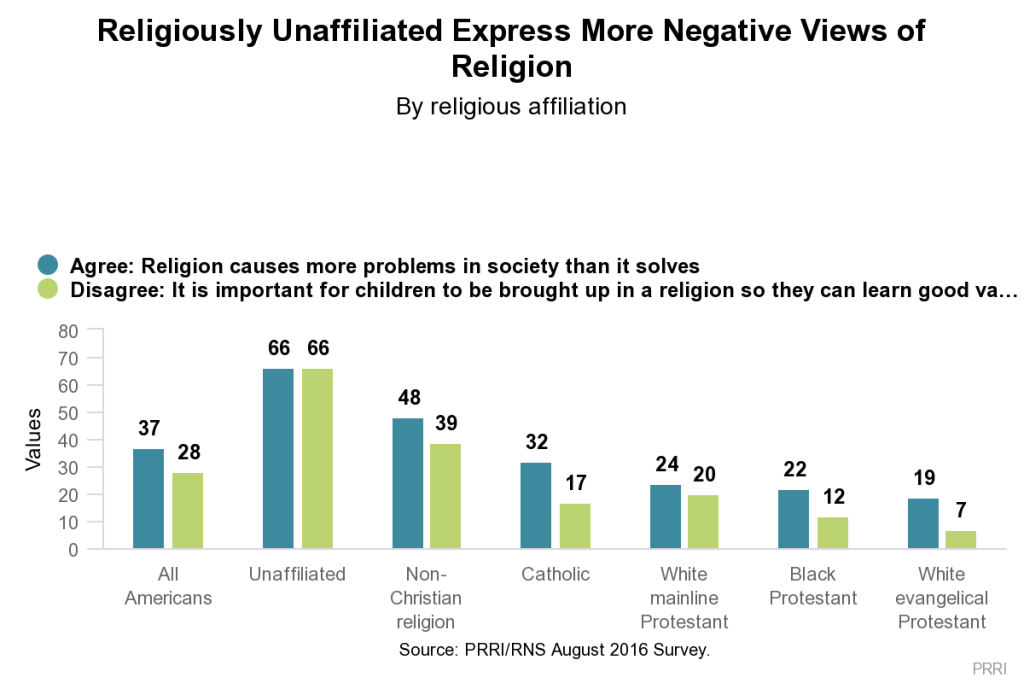

Overall, religiously unaffiliated and affiliated Americans hold significantly different views about the merits of organized religion, both for themselves and for society as a whole. About two-thirds (66%) of unaffiliated Americans agree “religion causes more problems in society than it solves.” In contrast, a majority of white evangelical Protestants (78%), black Protestants (74%), white mainline Protestants (72%), and Catholics (66%) disagree. Members of non-Christian religions are closely divided on this question (48% agree, 49% disagree).

Americans who are unaffiliated also reject the notion that religion plays a crucial role in providing a moral foundation for children. Approximately two-thirds (66%) of unaffiliated Americans believe it is not important for children to be brought up in a religion so they can learn good values. Overwhelming numbers of religious Americans, including white evangelical Protestants (92%), black Protestants (86%), Catholics (81%), white mainline Protestants (78%), and members of non-Christian religions (59%) believe religion is important in instilling good values in children.

Few unaffiliated Americans are actively looking to join a religious community. Only seven percent of the unaffiliated report they are searching for a religion that would be right for them, compared to 93% who say they are not.

Few unaffiliated Americans are actively looking to join a religious community. Only seven percent of the unaffiliated report they are searching for a religion that would be right for them, compared to 93% who say they are not.

In fact, relatively few unaffiliated Americans report they regularly devote much time to thinking about God or religion. More than seven in ten (72%) unaffiliated Americans say that in their day-to-day life, they do not spend much time thinking about God or religion. By contrast, a majority (54%) of Americans, including majorities of black Protestants (81%), white evangelical Protestants (80%), Catholics (54%), and white mainline Protestants (52%), disagree. Members of non-Christian religions are roughly divided on this question (51% agree, 49% disagree).

God, Morality, and Doubt

Despite their lack of connection to formal religious institutions, most unaffiliated Americans retain a belief in God or a higher power. A majority of unaffiliated Americans say God is either a person with whom people can have a relationship (22%) or an impersonal force (37%). Only one-third (33%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they do not believe in God. Strong majorities of Americans who belong to the major Christian religious traditions hold a personal conception of God. Compared to Christians, Americans who identify with a non-Christian tradition are significantly less likely to hold a personal conception of God (33%) and are more likely to say God is an impersonal force in the universe (49%).

Although most unaffiliated Americans do not reject outright a belief in God, they express many more doubts about the existence of a higher power than other Americans. A majority (53%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans say they sometimes doubt whether God exists, while more than four in ten (44%) disagree. In contrast, only six percent of white evangelical Protestants, 12% of black Protestants, 19% of white mainline Protestants, and roughly one-quarter (26%) of Catholics say they have doubts about God’s existence. Americans who identify with non-Christian religions are more likely than other religious Americans to say they sometimes doubt the existence of God (46%).

Religiously unaffiliated Americans are also less likely than religious Americans to link belief in God to moral behavior. Only about one in five (21%) unaffiliated Americans say it is necessary to believe in God to be moral and have good values. More than three-quarters (77%) reject this idea, including 61% who strongly reject it. A majority of black Protestants (78%), white evangelical Protestants (59%), and Catholics (59%) agree believing in God is a necessary precondition for moral behavior. Notably, fewer than half of white mainline Protestants (43%) and those who identify with non-Christian religions (43%) agree.

Sharing Religious Identity and Views about Religion

Although previous research has shown that atheists are viewed quite negatively among the public, most religiously unaffiliated Americans do not have qualms about sharing their religious beliefs or views about religion with their friends or family. Only 21% of unaffiliated Americans say they generally do not share their religious identity or views about religion with friends or family members out of fear of disapproval, while 76% say they have no problem doing this. Among Americans overall, eight in ten (80%) say they do not mind sharing their religious beliefs with friends or family.

Notably, young unaffiliated Americans (age 18 to 29) are roughly twice as likely as unaffiliated seniors (age 65 and older) to say they are not always open about their religious identity or beliefs with family members or friends (30% vs. 16%, respectively).

Understanding the Religiously Unaffiliated: Rejectionists, Apatheists, and Unattached Believers

The Three Subgroups: Rejectionists, Apatheists, and Unattached Believers

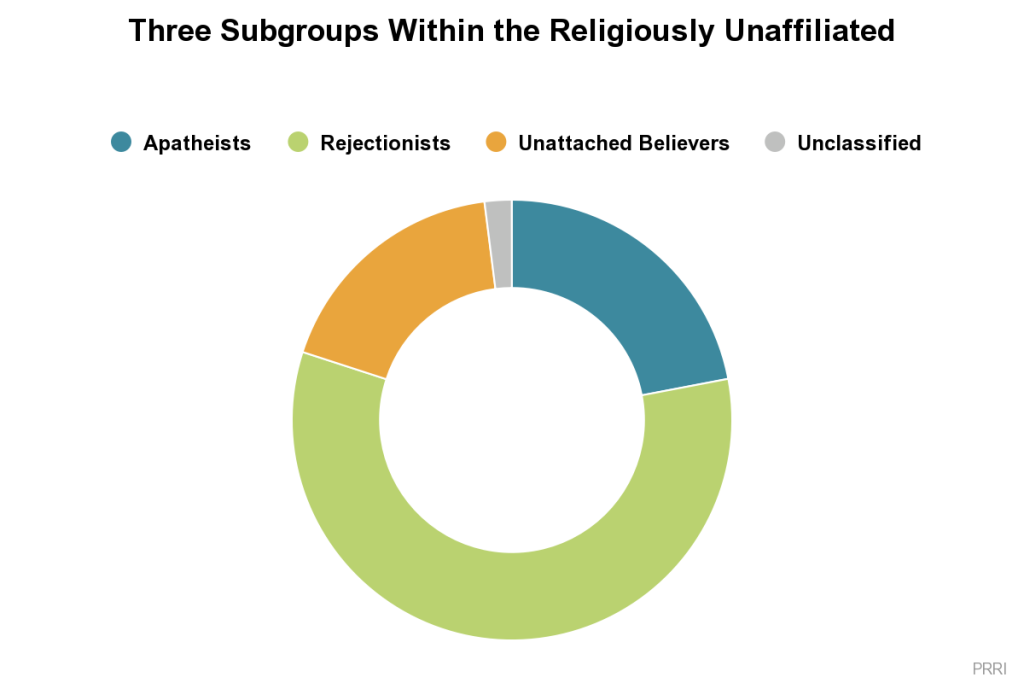

Religiously unaffiliated Americans are distinct from religious Americans in important ways, but there is also considerable diversity among this group. Using two separate questions that measure the personal relevance of religion and the perceived social benefit of religion, we identified three distinct groups among the unaffiliated: Rejectionists, Apatheists, and Unattached Believers.

Rejectionists, who account for the majority (58%) of all unaffiliated Americans, say religion is not personally important in their lives and believe religion as a whole does more harm than good in society. Apatheists, who make up 22% of the unaffiliated, say religion is not personally important to them, but believe it generally is more socially helpful than harmful. Unattached believers, who make up only 18% of the unaffiliated, say religion is important to them personally. For a full demographic profile of these three subgroups of religiously unaffiliated Americans, see Appendix 2.

Overall, religiously unaffiliated Americans are significantly younger than religiously affiliated Americans. Among the religiously unaffiliated subgroups, Rejectionists and Apatheists are substantially younger than Unattached Believers. More than one-third of Apatheists (38%) and Rejectionists (35%) are under the age of 30, compared to fewer than one-quarter (24%) of Unattached Believers.

Overall, religiously unaffiliated Americans are significantly younger than religiously affiliated Americans. Among the religiously unaffiliated subgroups, Rejectionists and Apatheists are substantially younger than Unattached Believers. More than one-third of Apatheists (38%) and Rejectionists (35%) are under the age of 30, compared to fewer than one-quarter (24%) of Unattached Believers.

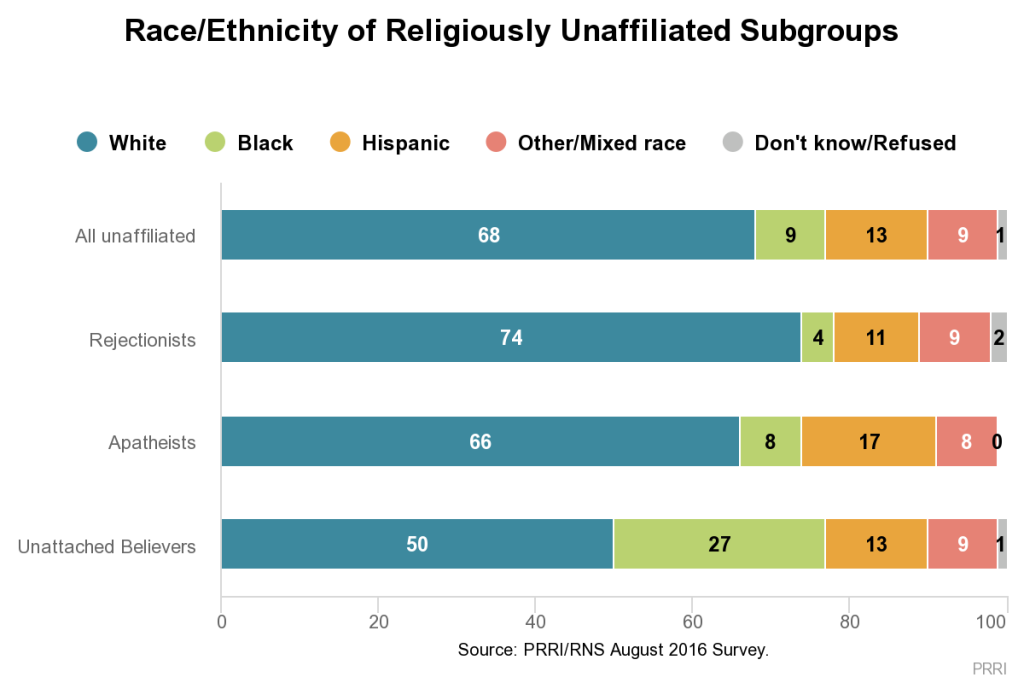

The racial composition of each group is also somewhat distinct. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Rejectionists and approximately two-thirds (66%) of Apatheists are white, non-Hispanic Americans. In contrast, only half (50%) of unattached believers are white. Fewer than one in ten Rejectionists (4%) and Apatheists (8%) are black, compared to 27% of Unattached Believers.

The racial composition of each group is also somewhat distinct. Nearly three-quarters (74%) of Rejectionists and approximately two-thirds (66%) of Apatheists are white, non-Hispanic Americans. In contrast, only half (50%) of unattached believers are white. Fewer than one in ten Rejectionists (4%) and Apatheists (8%) are black, compared to 27% of Unattached Believers.

Unattached Believers also stand out because they are significantly more likely than Rejectionists or Apatheists to live in the South (53% vs. 29% and 28%, respectively).

The gender ratio also varies considerably between the groups as well. Six in ten (60%) Apatheists and a majority (56%) of Rejectionists are men. In contrast, nearly six in ten (58%) Unattached Believers are women.

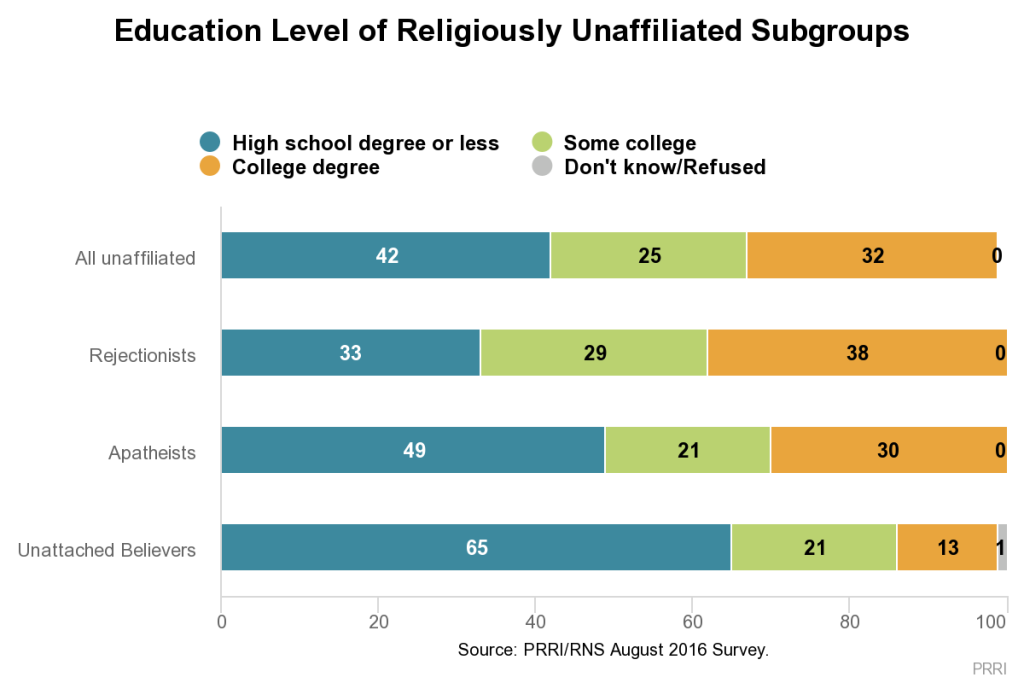

There are stark educational divisions between the groups. Nearly four in ten (38%) Rejectionists and three in ten (30%) Apatheists have a four-year college degree, compared to only 13% of Unattached Believers. Roughly two-thirds (65%) of Unattached Believes have a high school education or less, compared to roughly half (49%) of Apatheists and only one-third (33%) of Rejectionists.

There are stark educational divisions between the groups. Nearly four in ten (38%) Rejectionists and three in ten (30%) Apatheists have a four-year college degree, compared to only 13% of Unattached Believers. Roughly two-thirds (65%) of Unattached Believes have a high school education or less, compared to roughly half (49%) of Apatheists and only one-third (33%) of Rejectionists.

Religious Participation and Engagement

The approach and attitude towards religion also varies substantially among the unaffiliated. Rejectionists and Apatheists report similar patterns of worship attendance—more than three-quarters say they seldom or never attend formal religious services (83% and 76%, respectively). Fewer than four in ten (39%) Unattached Believers say they seldom or never attend religious services. More than six in ten (61%) say they attend at least a few times a year.

Rejectionists are unique among the unaffiliated for the degree to which they report a personally negative experience at a place of worship. More than one-quarter (27%) of Rejectionists report having had a mostly negative experience the last time they attended a worship service, while a majority (57%) say their last experience was primarily a positive one. At least eight in ten Apatheists (80%) and Unattached Believers (89%) say their last experience at a worship service was primarily positive.

Despite a generally positive view about the role of religion in society, few Apatheists are actively looking to join a religious congregation. In fact, Apatheists and Rejectionists are about equally as likely to say they are looking to join a religion (3% vs. 4%, respectively). Notably, even relatively few Unattached Believers (22%) say they are currently seeking to join a religious community or congregation.

Both Apatheists and Rejectionists show considerable disinterest in religion. Eighty-six percent of Apatheists and 79% of Rejectionists report they do not spend much time in their daily life thinking about God or religion. Only one-third (33%) of Unattached Believers say they do not contemplate God or religion regularly.

Views about God

Conceptions of God vary widely between the unaffiliated subgroups. Unattached Believers are far more likely than Apatheists or Rejectionists to hold a personal view of God (54% vs. 21% and 13%, respectively). Nearly half (47%) of Rejectionists say they do not believe in God, while fewer than one-quarter (22%) of Apatheists and just six percent of Unattached Believers say the same.

Rejectionists are also substantially more likely than Apatheists and Unattached Believers to report doubts about God. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of Rejectionists say they sometimes doubt whether God exists, a sentiment shared by fewer than half (49%) of Apatheists and only 24% of Unattached Believers.

Perceptions of the Link between Religion and Morality

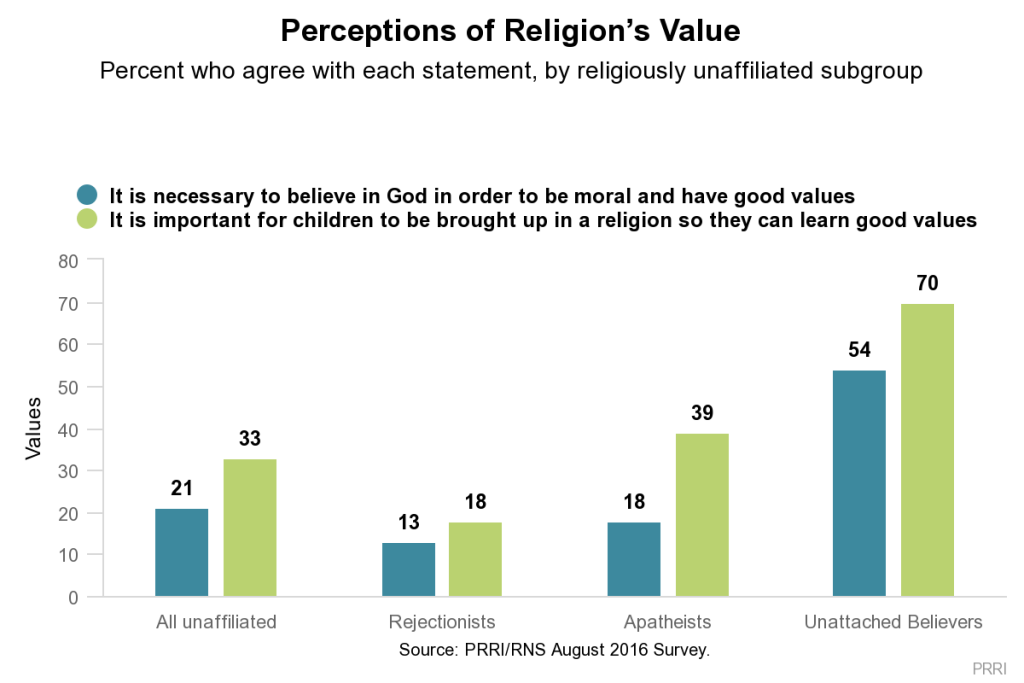

Unattached believers are significantly more likely than either Apatheists or Rejectionists to perceive a link between religious belief and membership on the one hand and the ability to have good morals and values on the other.

Seven in ten (70%) Unattached Believers agree children ought to be raised in religion so they can learn good values, a view shared by only about four in ten (39%) Apatheists and 18% of Rejectionists.

Similarly, a majority (54%) of Unattached Believers agree it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values. Less than one in five Apatheists (18%) and Rejectionists (13%) agree with this statement.

A Cultural Connection to Religion

A Cultural Connection to Religion

The religiously unaffiliated subgroups also diverge in the extent to which they report a cultural connection to religion. Roughly half (47%) of unaffiliated Americans overall say they have a connection to religion as part of their ethnic background or cultural heritage. The cultural connection is strongest among Unattached Believers. More than three-quarters (77%) of Unattached Believers say they still feel a cultural connection to religion even though they no longer identify with a particular denomination or tradition, compared to roughly half (51%) of Apatheists and 36% of Rejectionists.

(Not) Spiritual and Not Religious

The survey finds little evidence of a separate mode of “spirituality” distinct from “religiosity,” either among religious or religiously unaffiliated Americans. Rather, measures of traditional religiosity are positively correlated with self-identification as a “spiritual person.” Compared to other Americans, the religiously unaffiliated are considerably less likely to identify themselves as spiritual. Only four in ten unaffiliated Americans identify themselves as being very (14%) or moderately (26%) spiritual. Nearly six in ten say they are only slightly spiritual (26%) or not at all spiritual (32%). In contrast, more than two-thirds of Americans overall say they are very (30%) or moderately (38%) spiritual.

Rejectionists and Apatheists are much less likely than Unattached Believers to self-identify as spiritual. While more than seven in ten (71%) Unattached Believers describe themselves as at least moderately spiritual, only about one-third of Apatheists (31%) and Rejectionists (34%) identify this way.

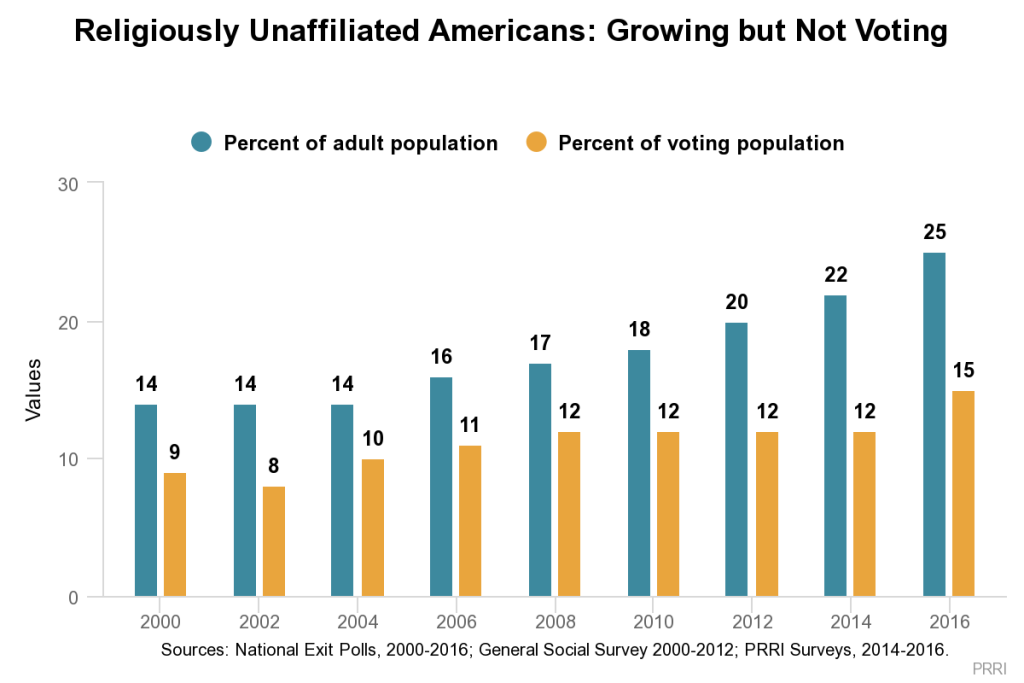

The Politics and Political Influence of the Unaffiliated

Despite their exponentially growing numbers, the political influence of religiously unaffiliated Americans has been muted. In 2004, religiously unaffiliated Americans comprised 14% of the public but only 10% of voters. By the last presidential election in 2012, religiously unaffiliated Americans had grown to comprise 20% of the public, but had grown only marginally to comprise 12% of voters. By way of comparison, in 2012 white evangelical Protestants also comprised 20% of the public, but they accounted for more than one in four (26%) voters because of higher voter registration and turnout rates.

It is likely religiously unaffiliated Americans will again be underrepresented at the ballot box this fall. Currently, more than one-quarter (26%) of unaffiliated Americans report they are not registered to vote, a significantly higher rate than among white evangelical Protestants (10%), white mainline Protestants (11%), or white Catholics (12%).

The political preferences of religiously unaffiliated Americans depart notably from those of most other religious groups. A plurality (48%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans are politically independent. One-third of the unaffiliated (33%) are Democrats and only 12% identify as Republican. Although the religiously unaffiliated are more likely to identify as independent than Democratic, they are about twice as likely to be politically liberal (41%) as they are to be conservative (21%). Three in ten (30%) are politically moderate.

The political preferences of religiously unaffiliated Americans depart notably from those of most other religious groups. A plurality (48%) of religiously unaffiliated Americans are politically independent. One-third of the unaffiliated (33%) are Democrats and only 12% identify as Republican. Although the religiously unaffiliated are more likely to identify as independent than Democratic, they are about twice as likely to be politically liberal (41%) as they are to be conservative (21%). Three in ten (30%) are politically moderate.

The 2016 Presidential Election

Interest in the Election

Consistent with their lower rates of voter registration, religiously unaffiliated Americans express less interest in the 2016 election, compared to white Christian groups. Fewer than four in ten (37%) religiously unaffiliated Americans say they are following news about the 2016 election very closely. Three in ten (30%) say they are following it fairly closely, while more than one-third (34%) say they are following the election not too closely or not at all closely. In contrast, a majority (56%) of white evangelical Protestants say they are following the election very closely.

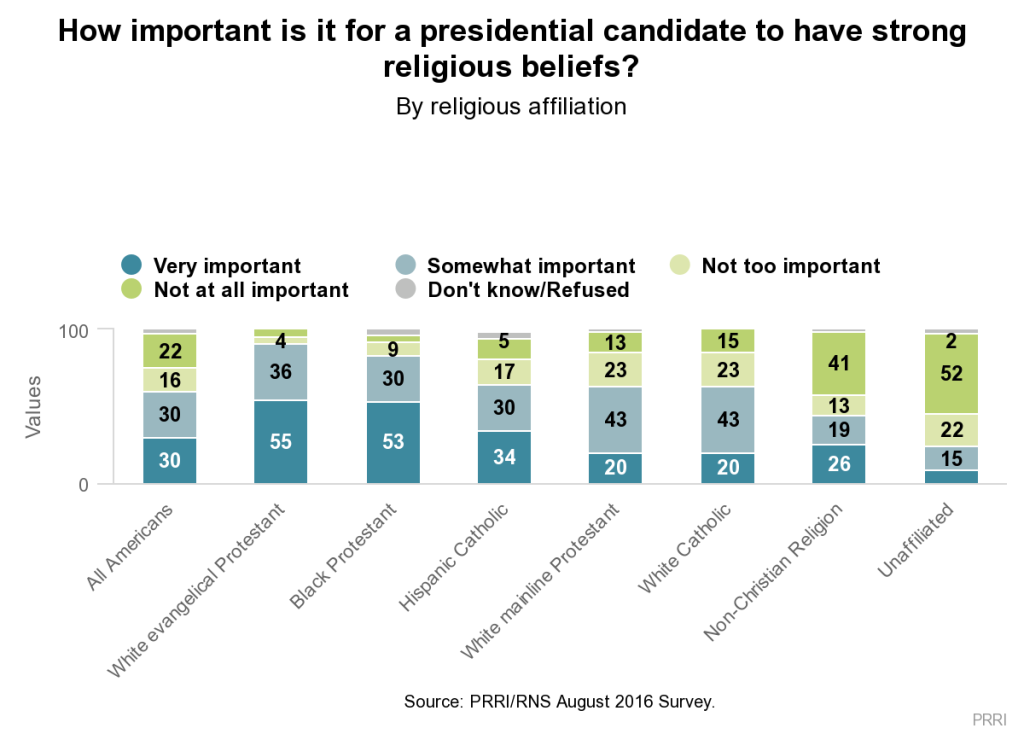

Most Americans say it is very important (30%) or somewhat important (30%) that a presidential candidate has “strong religious beliefs,” but unaffiliated Americans strongly reject this assertion. Fewer than one-quarter of religiously unaffiliated Americans say it is very important (9%) or somewhat important (15%) for a presidential candidate to have strong religious beliefs. Nearly three-quarters say it is not too important (22%) or not at all important (52%) that a candidate express strong religious beliefs.

Most Americans say it is very important (30%) or somewhat important (30%) that a presidential candidate has “strong religious beliefs,” but unaffiliated Americans strongly reject this assertion. Fewer than one-quarter of religiously unaffiliated Americans say it is very important (9%) or somewhat important (15%) for a presidential candidate to have strong religious beliefs. Nearly three-quarters say it is not too important (22%) or not at all important (52%) that a candidate express strong religious beliefs.

Voter Preference in the Election

At the start of the 2016 general election season in early August, religiously unaffiliated voters expressed a strong preference for Hillary Clinton over Donald Trump (62% vs. 21%, respectively). However, nearly one in five unaffiliated voters express support for another candidate such as Gary Johnson or Jill Stein (12%) or report no candidate preference at all (6%).

Clinton and Trump’s voting coalitions differ considerably in terms of each candidate’s proportion of support from white Christians, non-white Christians, and the religiously unaffiliated. Among Hillary Clinton’s supporters, seven percent are white evangelical Protestant, 12% are white mainline Protestant, 11% are white Catholic, 30% are religiously unaffiliated, and 15% are black Protestant. In contrast, among Donald Trump’s supporters, 33% are white evangelical Protestant, 19% are white mainline Protestant, 18% are white Catholic, 13% are religiously unaffiliated, and just one percent are black Protestant.

Recommended citation:

Jones, Robert P., Daniel Cox, Betsy Cooper, and Rachel Lienesch. “Exodus: Why Americans Are Leaving Religion – and Why They’re Unlikely to Come Back.” PRRI. 2016. http://www.prri.org/research/prri-rns-poll-nones-atheist-leaving-religion/.