Ansley Quiros, Ph.D., is a 2024-2025 PRRI Public Fellow, Associate Professor of History, and Chair of the Department of History at the University of North Alabama. She studies race and religion in American life.

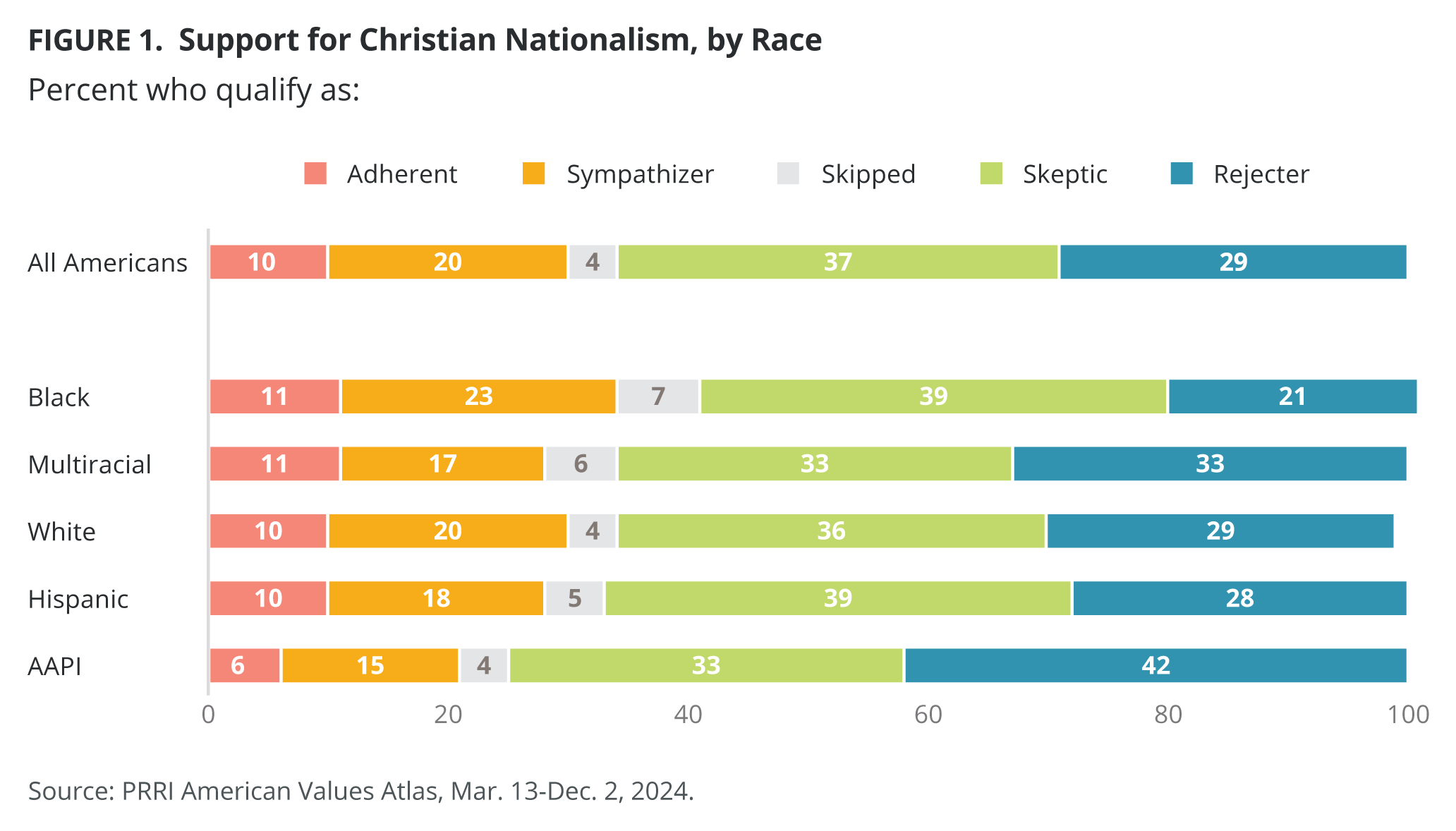

According to the 2024 PRRI American Values Atlas, Black Americans are more likely to hold Christian nationalist beliefs, at 34%, than other groups of Americans, including 30% of white Americans, 28% of both multiracial and Hispanic Americans, and 21% of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Such a finding is initially counterintuitive, given that the most outspoken Christian nationalist leaders are far less likely to be racially diverse and that Black Americans identify as Democratic, and vote for Democratic candidates, at much higher levels than other Americans. In 2024, PRRI’s Post-Election Survey found that 81% of Black Americans voted for Kamala Harris.

How can this solid Democratic constituency, then, also qualify as Christian nationalists at slightly higher rates than other Americans? This Spotlight examines why some Black Americans hold Christian nationalist views. The tendency for some Black Americans to qualify as Christian nationalists is rooted in religious and theological beliefs, grounded in a specific history that has shaped unique conceptions of what the concept of a “Christian America” means to many Black Americans.

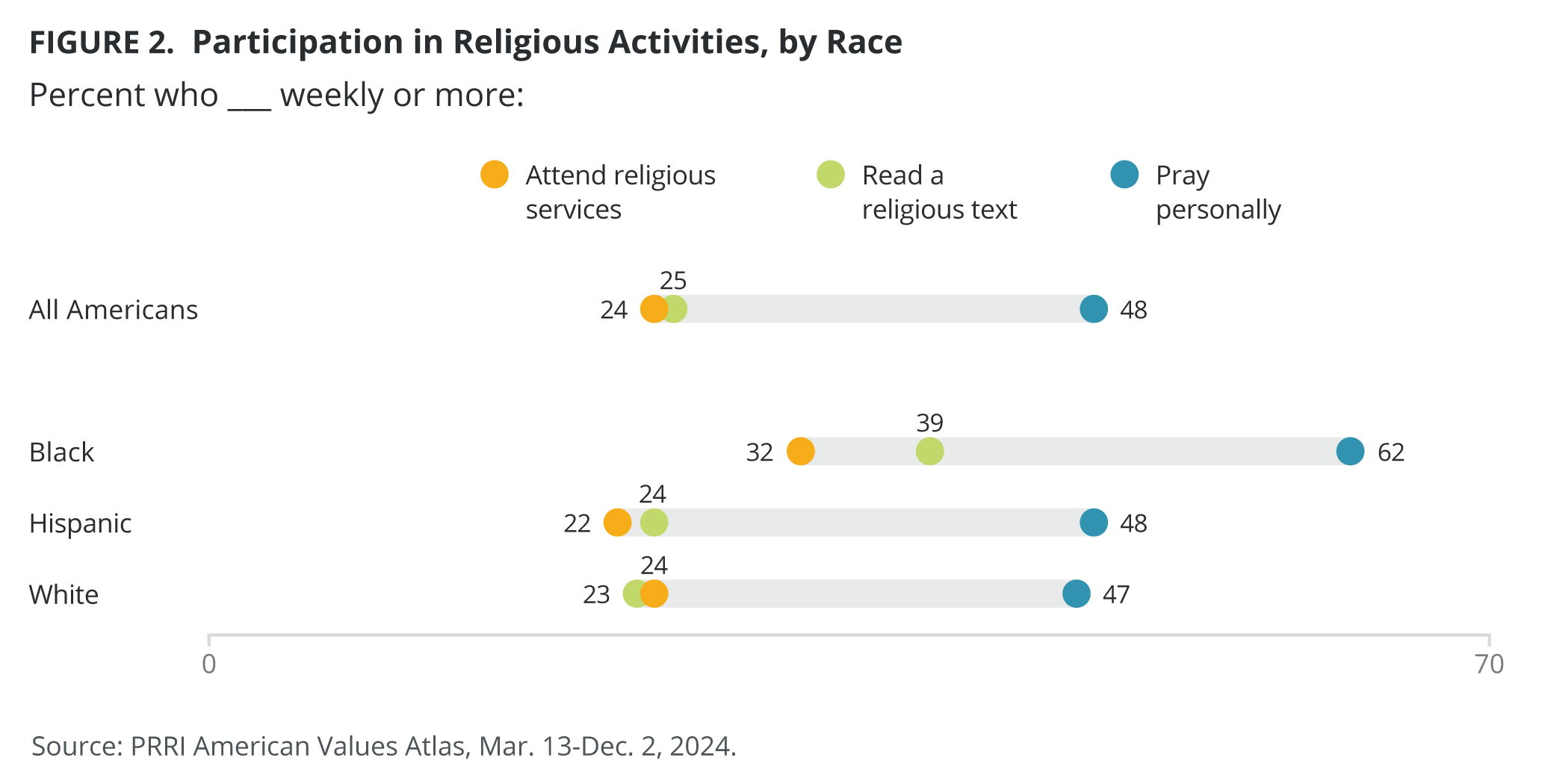

The fact that Black Americans are more religious than other Americans helps us to understand their relatively high levels of Christian nationalist beliefs. More than six in ten Black Americans (62%) say they personally pray weekly or more, 39% say they read the Bible (or another sacred text) weekly or more, and 32% say they attend religious services weekly or more. On all measures, Black Americans are significantly more devout than Hispanic and white Americans.

Notably, Christian nationalist views are more prevalent among Black Americans who attend religious services frequently than those who never or seldom attend (46% vs. 23%), and controlling for other factors helps us predict which Black Americans are more likely to hold Christian nationalist views.

Charismatic theology and worship practices also drive Black Americans to hold Christian nationalist views. Similar to white and Hispanic Americans, holding charismatic and prosperity gospel theological beliefs strongly predicts Christian nationalist views among Black Americans. On these measures, which includes speaking in tongues, believing in divine healing, or having experienced the “Spirit” empowering them or someone else to do a specific task, Black Americans report far higher levels than other Americans.

Moreover, the idea of a Christian nation as a component of Christian nationalism beliefs carries very different historical connotations for Black Americans. In his classic text Exodus!, Eddie Glaude argues that Black national consciousness, as it emerged in the 19th century, was deeply intertwined with Black Christian identity. Black Americans had a religiously animated sense of peoplehood and understood themselves correctly as a nation in a nation with, as Glaude put it, an “ambivalent relation” to the slaveholding state. These intellectual and political traditions rightly complicate the meanings of Black Christian nationalism.

Scholar and minister Esau McCauley, for example, reads abolitionist Frederick Douglass’ critique of Americans’ slaveholding Christianity as an argument essentially for Christian nationalism. “A Christian nation,” was not, according to Douglass, “a status to be claimed but a reality to strive for.” Decades later, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would echo these ideas, calling America to be more Christian in its love ethic, not less. In his sermon “Letter to the American Christians,” delivered first at Dexter Avenue in 1956, King imagines the apostle Paul urging the American Church to “keep your moral advances abreast with your scientific advances” and “live as Christians in the midst of an un-Christian world.” By this, King did not mean that Christians should assert and wield financial or political power, but that they should avoid the “tragic exploitation” of misused capitalism, “division and disunity,” and racial segregation.

The call for a more inclusive democracy that fought for racial and economic justice was rooted in Black theology and demanded a more active role for government to assert those goals. Tellingly, when we consider one of the questions about the relationship between Christianity, American identity, and the U.S. government that makes up PRRI’s Christian nationalism scale, three in ten Black Americans (30%) agree that God has called Christians to exercise dominion over all areas of American society, compared with just 19% of white Americans and 22% of Hispanic Americans. Yet what “Christian dominion” means for white, Hispanic, and Black Americans varies significantly, reflecting diverse historical experiences and theological traditions.