What About the [Immigrant] Children? Looking at 10 Years of DACA

DACA turned ten years old in 2022, providing an opportunity to reflect on how the United States and its policies have treated immigrant children during the past decade. In 2012, President Barack Obama signed an executive order titled Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). The policy allowed for certain undocumented immigrants who entered the United States as children to be protected from deportation, provided them an opportunity to obtain a work permit, provided additional benefits for migrant children to attend college, and reduced barriers to social incorporation.

Policies like DACA are viewed favorably by the public. In PRRI’s 2022 American Values Survey, 32% of respondents said that DACA should stay in place as it is, with DACA recipients, also known as Dreamers, required to apply for renewal every two years. Meanwhile, 41% of respondents thought the policy should be more generous and allow Dreamers to apply for permanent residency or citizenship.

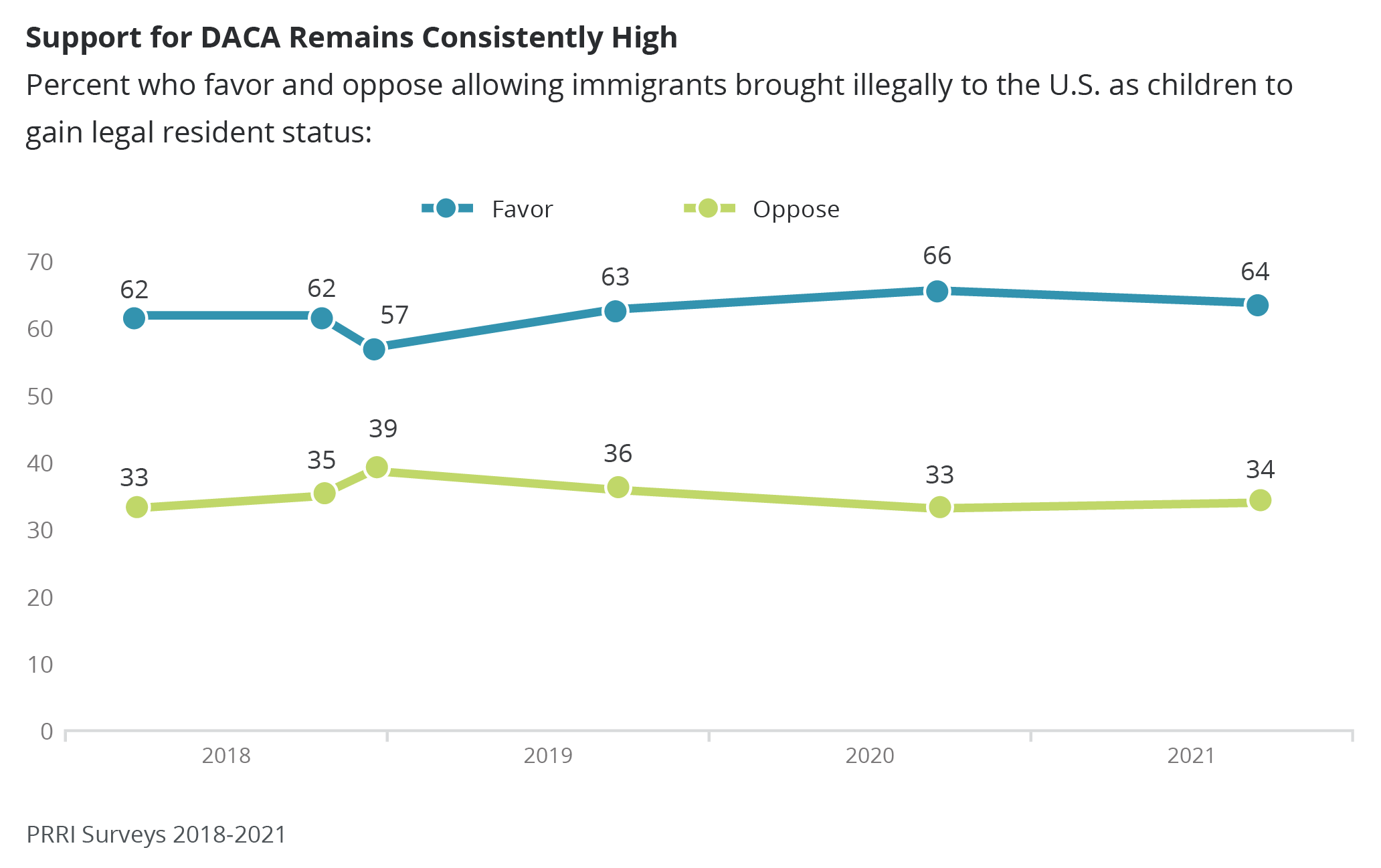

Public support for DACA has remained high over the past decade, according to PRRI data. Between 2011 and 2017, support for DACA increased among Americans as a whole, including among both Democrats and Republicans. PRRI data from 2018-2021 shows support for DACA remaining consistent. During this time frame, solid majorities of Americans — 57% up to 64% — support DACA, while approximately one-third opposed the policy.

Despite support for DACA, the past decade has also seen the United States undertake policies and actions that have been harmful to immigrant children. Two years after Obama signed DACA, protests arose against unaccompanied immigrant children entering the United States. Anti-immigrant activists organized blockades to stop buses that were transporting children to shelters. Elsewhere, people carried semi-automatic guns while they marched in protest of immigrant children arriving in their neighborhoods. I have found in my research that these protests were accompanied by racializing these immigrant children as criminals, threats to the economy, diseased, and as invaders. In reaction, the Obama administration developed a plan to fast-track the deportation of these children.

In 2018, four years after the protests against unaccompanied minors, the Trump administration implemented a new punitive measure that separated more than 5,000 migrant children from their families. Family separations were part of the Trump administration’s “zero tolerance” approach to deterring migrants from entering the United States. However, this policy led to an increasing need for detention space, since most detention sites were not equipped to detain children without their parents. As a result, the Trump administration started sending children to newly created “tent cities,” which are more expensive to operate than it would be to keep children with their parents and harken to the tent city jail of Sheriff Joe Arpaio, which was often compared to concentration camps. Since the end of the family separation policy, reports have indicated that the Trump administration did not have a plan to reunify families and there are still families that have not been reunited.

On the education front, there has been a multi-year battle in Texas over whether undocumented college students should qualify for in-state tuition rates. Conservative groups have long fought a 2001 Texas policy, House Bill 1403, that allowed certain undocumented students to qualify for in-state college tuition at state schools. Like DACA, the policy is intended to benefit immigrants who entered the country as children. A recent lawsuit against the University of North Texas (UNT), filed by the Young Conservatives of Texas at UNT, has placed HB 1403 in jeopardy. The law is still in effect, and the lawsuit currently only affects UNT, but there is a fear that economic pressures and pre-existing federal laws might undo the policy, stripping undocumented students of in-state tuition and, for many, access to higher education.

As the 10-year anniversary of DACA has come and gone, the struggle for the rights of immigrant children and DACA recipients continues. DACA was temporarily suspended by the Trump administration in 2017. It was restored in 2020 but has come under threat as part of the ongoing case Texas v. United States, in which Texas and other states have argued that Obama lacked authority to create the program. The latest judgement in the case has put processing new applications on hold, although renewals are still being processed. Given both the consistent public support for programs like DACA and the threats against benefits for young migrants, the program needs to be codified into law to strengthen it beyond the executive action that created it.

Luis Romero is a members of the 2022-2023 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.