The recent midterm elections have reignited public debates about the role of personal morality in the private lives of elected officials. In the 2016 presidential election, the majority of white Christian voters supported Donald Trump, including 81% of white evangelicals—a group whose espoused moral convictions seemed to blatantly contradict the private proclivities of the candidate.

In the 2022 midterms, there was no shortage of candidates who had the support of the nation’s most populous religious communities, even though their morals seemed to fall short of those communities’ articulated standards. Before the election, Astead Herndon, host of the New York Times podcast “The Run-Up,” interviewed Al Mohler, president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, to ask him about this seeming incongruity. Mohler told Herndon that he believed Christian voters should prioritize two issues: “the sanctity of human life and the integrity of marriage.” On the surface, Mohler’s response provides a simple explanation for many Christians’ seeming disregard of the personal morality of political candidates: abortion and marriage equality seem to be the central issues that galvanize evangelical voters. However, PRRI’s American Values Survey suggests that white evangelical Christians are far from the only group willing to overlook personal immorality among elected officials.

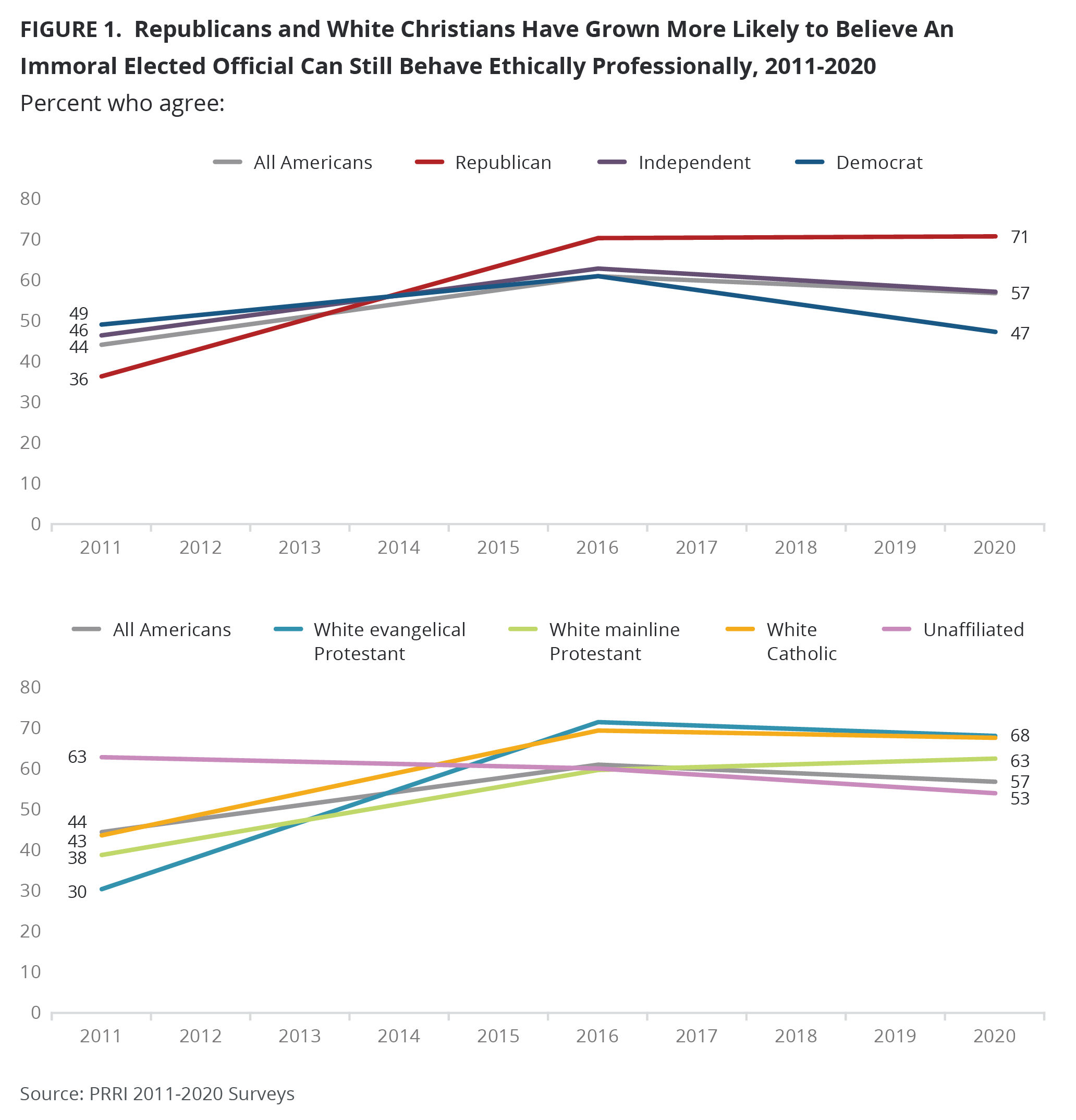

Key finding No. 1: Americans have grown more likely to believe that an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public and professional life. The percentage of Americans who agreed with this statement went from 44% in 2011 to 57% in 2020, with a significant spike in the run-up to the 2016 election, when 61% agreed. Republicans are the political group that showed the biggest change: Only 36% of Republicans agreed with this statement in 2011, but in 2020 they were about twice as likely to do so (71%). The percentage of independents who agreed rose as well, from 46% in 2011 to 57% in 2020. Democrats’ views have largely remained the same from 2011 to 2020 (49% and 47%, respectively), with one notable exception: In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election, 61% of Democrats said they were willing to overlook the personal immorality of an elected official, which suggests that no party is immune from fluctuations on the issue of politicians’ morality.

Key finding No. 2: The belief that an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically and fulfill their duties in their public and professional life increased among white Christians between 2011 and 2020.

Despite the media’s ongoing attempts to understand why white evangelical Christians in particular might overlook the immoral personal behavior of elected officials, this attitude is shared by multiple religious demographics. It is true that white evangelicals saw the highest increase in willingness to overlook immorality in politicians (from 30% in 2011 to 68% in 2020), but they were closely followed by white mainline Protestants (from 38% to 63%) and white Catholics (from 43% to 68%). By contrast, religiously unaffiliated Americans have become less likely to overlook the personal immorality of elected officials, with the percentage dropping from 63% in 2011 to 53% in 2020.

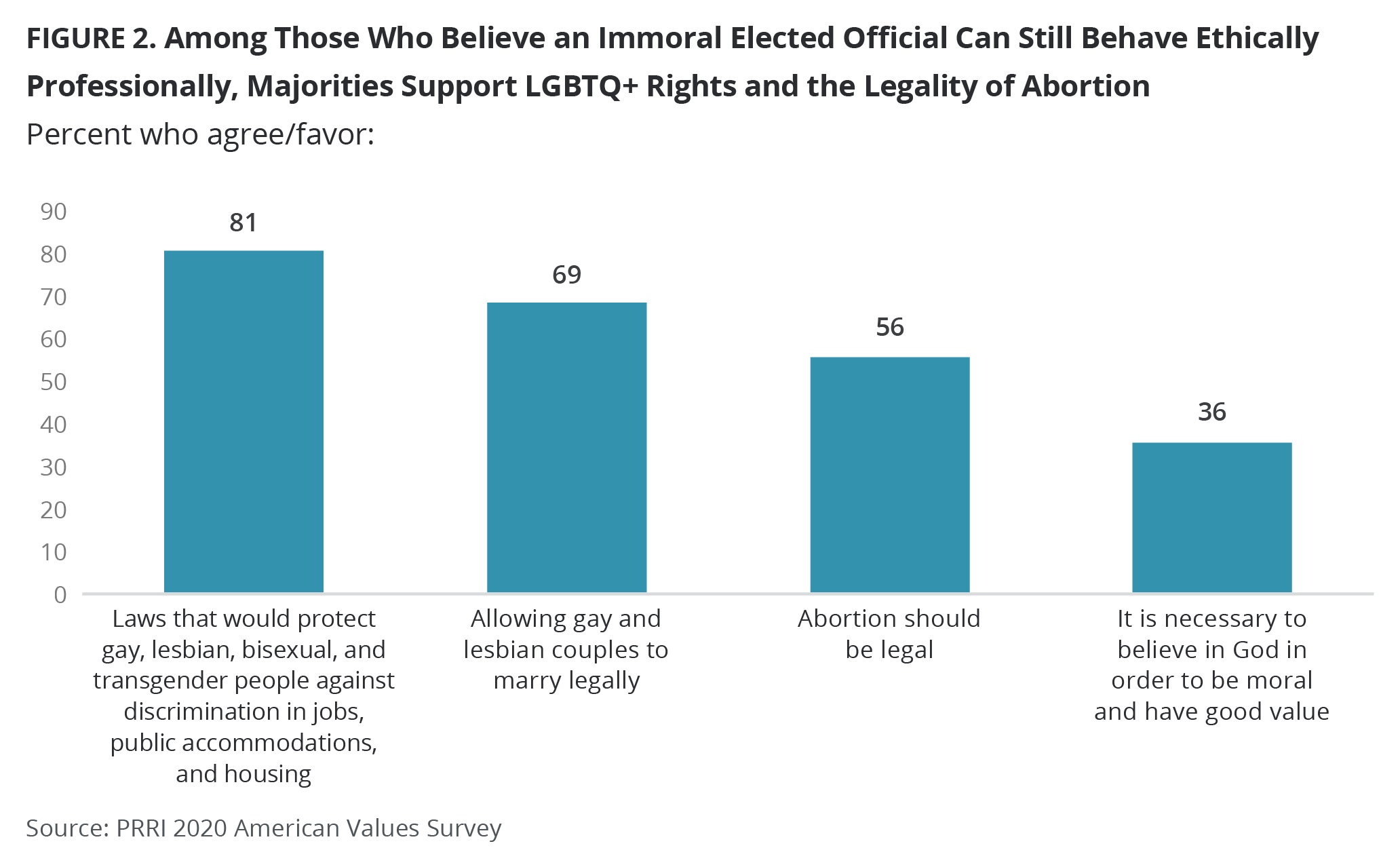

Key finding No. 3: Among Americans who believe that an elected official who commits an immoral act in their personal life can still behave ethically in public life, the majority support same-sex marriage and favor laws that would protect LGBTQ+ people against discrimination. They also think that abortion should be legal and do not think it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

Though white evangelicals may justify their willingness to overlook elected officials’ moral failings by explaining that they prioritize dismantling marriage equality and criminalizing abortion, these issues do not appear to motivate other Americans who are willing to overlook personal immorality. In fact, the majority of respondents who believe that an immoral elected official can still behave ethically in public and professional life do not share white evangelicals’ views on LGBTQ+ rights, abortion, or religion. Of this group as a whole 69% favor allowing gay and lesbian couples to marry; 81% favor anti-discrimination laws that would protect gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people against discrimination in jobs, public accommodations, and housing; 56% believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases; and 63% either completely disagree or mostly disagree that it is necessary to believe in God in order to be moral and have good values.

Together, these findings suggest that Americans’ increased ability to overlook the private transgressions of elected officials is not limited to white evangelicals but rather transcends political and religious affiliation. Among people who are willing to tolerate personal immorality in politicians, most do not support the stated white evangelical priorities of criminalizing abortion and revoking the legality of same-sex marriage. This shared willingness to overlook the private moral failures of public officials suggests that the tumult of the past decade may have convinced many Americans that political expediency can trump personal integrity.

Suzanna Krivulskaya, Ph.D., is a member of the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 cohorts of PRRI Public Fellows.