Saturday, June 20 marks 20 years since the United Nations first announced World Refugee Day, a day dedicated to raising awareness of the plight of refugees around the globe. A refugee is a person who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her country of origin because of “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion..[1]

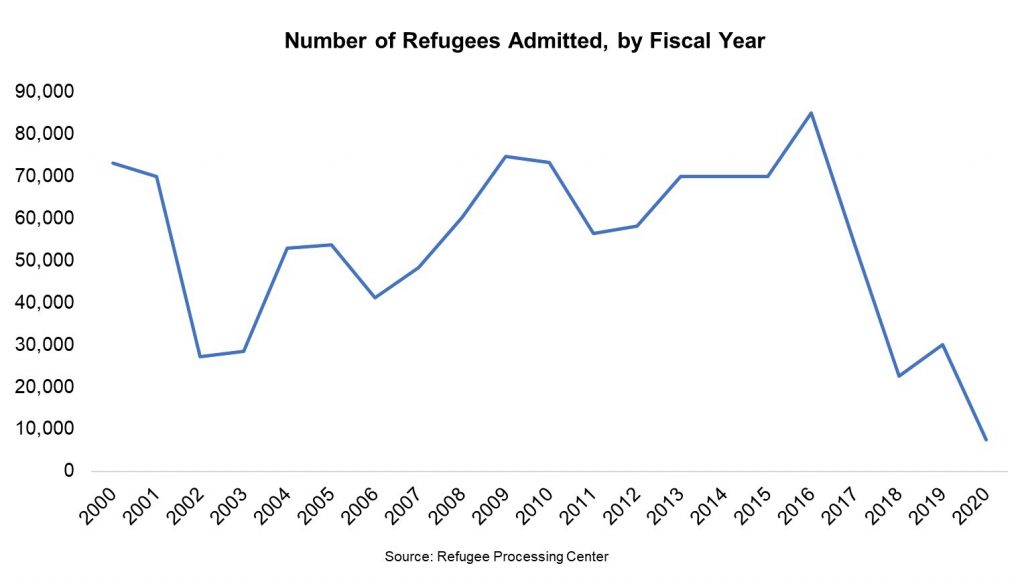

The United States has been a global leader in hosting refugees until recently. With the election of President Trump, there have been dramatic changes to U.S. asylum policy and the number of refugees admitted to the United States. These changes have resulted in the lowest admission of refugees since the refugee program was created in 1980. Refugee admissions went from less than 54,000 refugees admitted in 2017 to less than 8,000 refugees so far. The 2020 refugee admission ceiling is fixed at 18,000 refugees, the lowest level on record. And with the ongoing pandemic, the U.S. has basically closed its borders. What do Americans think about U.S. asylum policy?

Since 2017, PRRI survey data has asked Americans how strongly they favor or oppose passing a law to prevent refugees from entering the United States. Opinions have remained fairly stable among Americans since the question was first asked. Even though opposition to this law went up from 59% in 2017 to 64% in 2019, this change is not significant. About one-third of Americans supported this law in 2017 (36%) and in 2019 (35%). There are clear partisan divides on this question, however, and opinions have remained stable since 2017. More than three in four (77%) Democrats and almost two-thirds (64%) of independents, compared to only 42% of Republicans, oppose preventing refugees from entering the United States.

Majorities of Americans across various demographics oppose passing a law to prevent refugees entering the United States, including race, age, education, region, and even religious affiliation. White evangelical Protestants are the only religious group where the majority (54%) favors the passage of this law.

Many of the changes in U.S. asylum policy under the Trump administration have focused on preventing asylum seekers from Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala — countries belonging to the better known “Northern Triangle region.” Asylum seekers no longer wait in the United States until their claims are processed. Instead, they are required to wait in Mexico or sent to Northern Triangle countries to seek asylum there — places where asylum seekers are fleeing extreme levels of violence as a consequence of organized crime, drug trafficking, and the proliferation of gang activity.

In 2014, for example, during the peak of violence in these countries, inflows of unaccompanied children and mothers fleeing these countries grew exponentially. PRRI data from 2014 asked Americans which of the following statements came closer to their views. Once again, an overwhelming majority of Americans (69%) said that children arriving from Central America should be treated as refugees and should be allowed to stay in the U.S. if authorities determine it is not safe for them to return to their home country, while only 27% said that children arriving from Central America should be treated as illegal immigrants and should be deported to their home countries.

Most recently, the Trump administration published a new regulation (undergoing public comment) with a series of changes making it more difficult for migrants to claim asylum in the United States. One key proposed change is to redefine “membership in a particular social group,” which in the past helped victims of gang violence. With the new rule, it is believed that a significant number of legitimate asylum seekers will be excluded.

[1]When a person travels directly to the country he or she is seeking refuge, this person is called “asylum seeker,” and when this person flees to another country and waits there for an opportunity to resettle in a third country, this person is called “refugee for resettlement.”