Christian Nationalism: A ‘Stained-Glass Ceiling’ for LGBT Candidates?

White Christian nationalism has become a focus of political discussion in America in recent years as American conservatives and many prominent Republicans have embraced the personalities and ideas of this political orientation. In addition to the attention paid to the subject by the media and prominent politicians, some political commentators have pointed out that legislation targeting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, eliminating anti-racist subjects in schools, and attacking reproductive rights is influenced by the principles of white Christian nationalism.

But what is white Christian nationalism, and how does it affect political decisions that implicate gender and sexuality? In a recent article, I answer this question by focusing on the relationship between Christian nationalism and support for LGBT political candidates. I find that Christian nationalists are less likely to support LGBT candidates, and the negative effect of Christian nationalism transcends partisanship, race, and religious affiliation. In short, LGBT political candidates are viewed by Christian nationalists as embodiments of deviant behavior and as conduits for policy changes that would undermine the nationalists’ preferred social order. Because Christian nationalism is a persistent feature of American politics and can have negative effects on support for LGBT candidates even among traditionally supportive groups, it will likely remain a barrier to LGBT representation and policy success in future elections.

What Is Christian Nationalism?

Christian nationalism is defined by scholars as a “cultural framework that idealizes and advocates a fusion of Christianity with American civic life.” But what does this look like in practice? PRRI’s American Values Survey shows that almost three-quarters of Americans believe the United States has always been a force for good in the world, and more than half say there has never been a time when they were not proud to be American. Numerous surveys also show that a majority of Americans affiliate with a Christian religious tradition. Do these findings mean a majority of Americans are Christian nationalists?

In short, no. That is because Christian nationalism is not just about religious affiliation or about being a proud American. The “fusion” of Christianity with American civic life refers not just to the idea that America is a nation founded by Christians, but that current American social and political institutions should explicitly privilege conservative Christian beliefs—to the extent that conservative Christians are understood to be white, straight, and cisgender.

The important thing to remember about religious nationalist movements wherever they occur is, one, they are explicitly political, and as such, religious nationalists are more likely to support actions by the state to both privilege their views in public policy and suppress their political opponents’ ability to challenge their political power. Second, largely because of their preference for authoritarianism and state-sponsored coercion to establish a singular definition of who is or can be a citizen, adherents to religious nationalist political ideals often express different policy preferences than religious people.

For example, white Christian nationalists in the United States are more likely to believe that police treat Black and white Americans the same, and that police shootings of Black Americans occur because Black people are more violent. Religious Americans—that is, people who regularly participate in religious activities and believe faith is important in their lives—are more likely to hold the opposite views. Survey data show similar patterns for attitudes toward religious minorities and immigrants.

White Christian nationalism and religiosity, though, can have similar effects on attitudes about sexuality, gender, and family. That is because both white Christian nationalists and most very committed religious people in America are more likely to believe that gender is a key, unchanging organizing principle of society and the heterosexual family is the safeguard for society’s values. How are these views applied to vote choices, and what does that mean for LGBT candidates?

Christian Nationalism: A Stained-Glass Ceiling

My recent research answers these questions using data from the CalSpeaks survey, which periodically measures attitudes and behaviors of non-institutionalized Californians over the age of 18. This survey used a subsample (about 700 people) of the regular CalSpeaks panelists to ask specific questions designed by a small group of researchers. In this case, I asked survey participants if they supported lesbian and gay or transgender candidates for different levels of political office, as well as several questions designed to measure support for the principles of Christian nationalism, like believing the federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation.

With respect to Christian nationalism, I found that about 10% to 20% of Californians support the principles of Christian nationalism that I measured in the survey. I also found that Republicans, conservatives, and those who attend church frequently are more likely to agree with the principles of Christian nationalism I measured.

With respect to vote choices, on average, Christian nationalism is associated with about a 40% decrease in support for both gay and lesbian or transgender candidates for political office. For comparison, an increase in church attendance among the sample is only associated with about a one percent decrease in support.

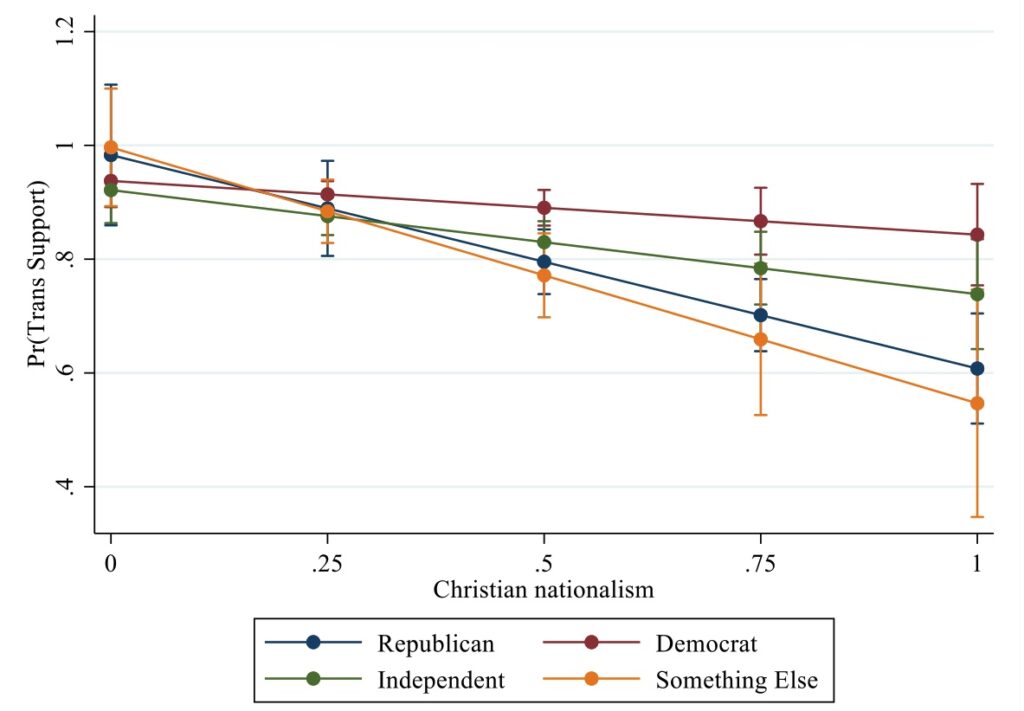

It is important to note that the findings do not mean adherents of Christian nationalism are only drawn from among Republicans, conservatives, and religious people. Democrats, independents, progressives, moderates, and people of color can also adhere to Christian nationalist principles. This is important because among these groups, who are traditionally supportive of LGBT rights and candidates, Christian nationalism appears to erode that support. As the figure shows, support for transgender political candidates decreases as Christian nationalism increases across all partisan groups I surveyed.

In addition to partisanship, my findings show the negative effects of Christian nationalism also transcend race and religious affiliation. Support for LGBT candidates decreases across all religious and racial groups in my sample as Christian nationalism increases. The findings suggest that Christian nationalism helps solidify opposition to LGBT political candidates because they represent challenges to heterosexuality and traditional gender roles, but also because they represent challenges to straight and cisgender political power. Because the effects persist among groups who are traditionally supportive of LGBT rights, the barrier of Christian nationalism likely represents a ceiling on support for LGBT candidates among the American electorate.

R.G. Cravens III is a member of the 2021-2022 cohort of PRRI Public Fellows.