Religious Identities and the Race Against the Virus: (Wave 2: June 2021)

Executive Summary

To view a PDF of slides presented at the July 28, 2021, webinar, click here: PRRI IFYC Vaccine And Religion II Presentation. To view a replay of the webinar via YouTube, click here: PRRI-IFYC Religious Diversity and Vaccine Survey Briefing.

The June 2021 Religion and the Vaccine Survey, conducted jointly by PRRI and IFYC, updates and expands on the March 2021 PRRI–IFYC Religion and the Vaccine Survey, documenting how faith-based approaches supporting vaccine uptake can—and did—influence members of key hesitant groups to get vaccinated, as well as which groups pushed the country closer to vaccination goals and which groups still lag behind.

The U.S. fell short of the 70% vaccinated goal that the Biden administration set for the July 4th holiday, but it came close. While many states and localities did achieve that goal, the second quarter of 2021 also saw increasing disparities between state vaccination rates—disparities that are driven by a complex range of factors, including political affiliation, religious affiliation, race, and socioeconomic status.

Vaccine hesitancy is down, and acceptance is up.

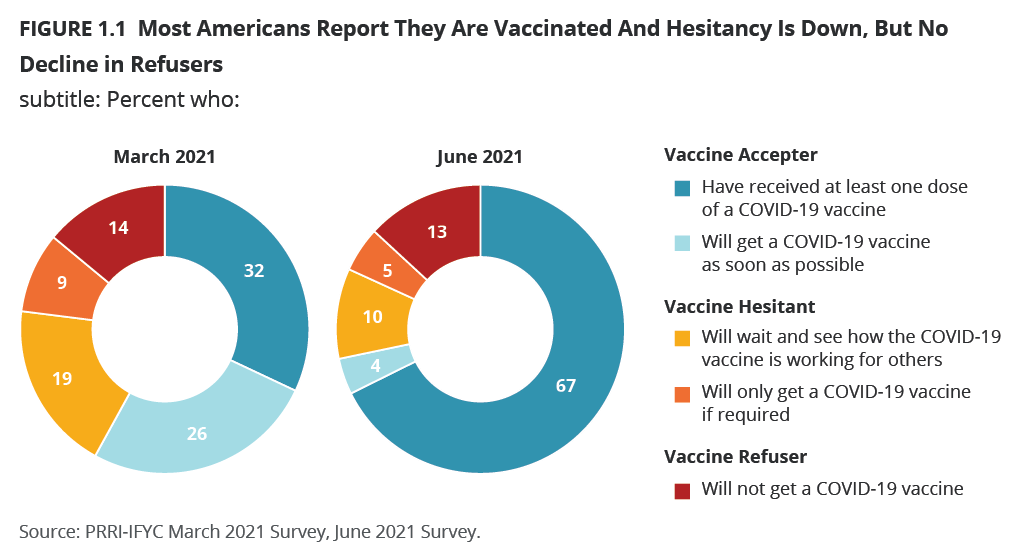

- Two-thirds of Americans (67%) report having received at least one dose of a vaccine, and another 4% say they will get vaccinated as soon as possible. Less than one in five (15%) are hesitant, a decrease from 28% in March, and 13% say they will not get vaccinated, similar to the 14% who said they would not get vaccinated in March.

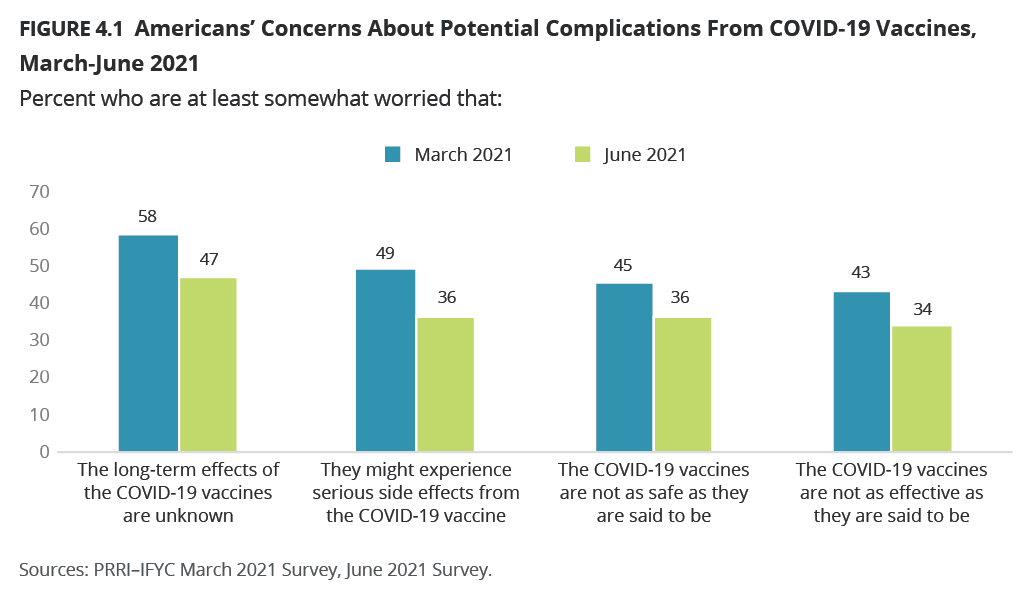

- The proportion of Americans who worry that the long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccines are unknown dropped more than 10 percentage points, from 58% in March to 47% in June.

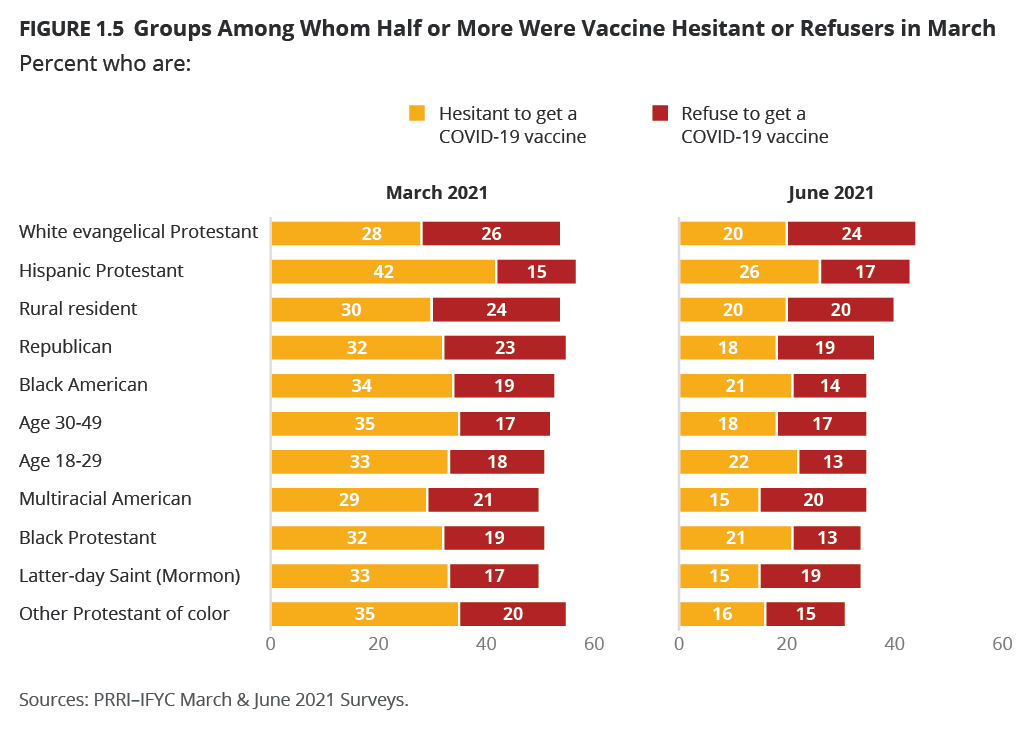

- Refusals have held steady across most demographic groups, although some subgroups have become significantly less likely to say they will refuse to get vaccinated, including, notably, Black Protestants (19% said they would refuse in March; 13% said they would refuse in June) and Republicans (23% said they would refuse in March; 19% said they would refuse in June).

- Among religious groups, Hispanic Catholics have increased most in vaccine acceptance, from 56% in March to 80% in June. Nearly eight in ten white Catholics (79%) are also vaccine accepters, up from 68% in March. Other non-Christians (78%), other Christians (77%), the religiously unaffiliated (75%), and white mainline Protestants (74%) are also above the 70% mark, with increases of 11-15 percentage points in each group.

- Parents are more hesitant to get their children vaccinated than they are to get themselves vaccinated, but there is a close relationship between hesitancy for adults and children. Among those who are vaccine acceptant, 56% are vaccine acceptant for their children; among vaccine hesitant parents, 81% are hesitant to get their children vaccinated; and vaccine rejecters almost universally will not get their children vaccinated (94%).

Faith-based approaches still have the potential to be effective for hesitant and refusing groups. There is also evidence these strategies have impacted decisions.

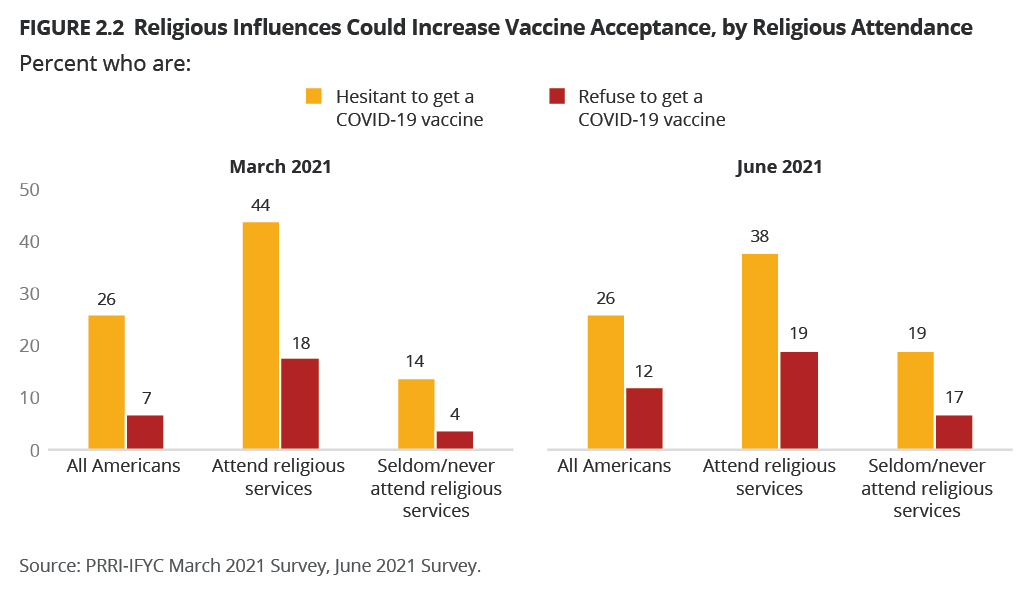

- Nearly four in ten vaccine hesitant Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year (38%) say one or more faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- Even among refusers, these approaches could be effective. Nearly one in five Americans who are vaccine refusers (19%) also say one or more faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

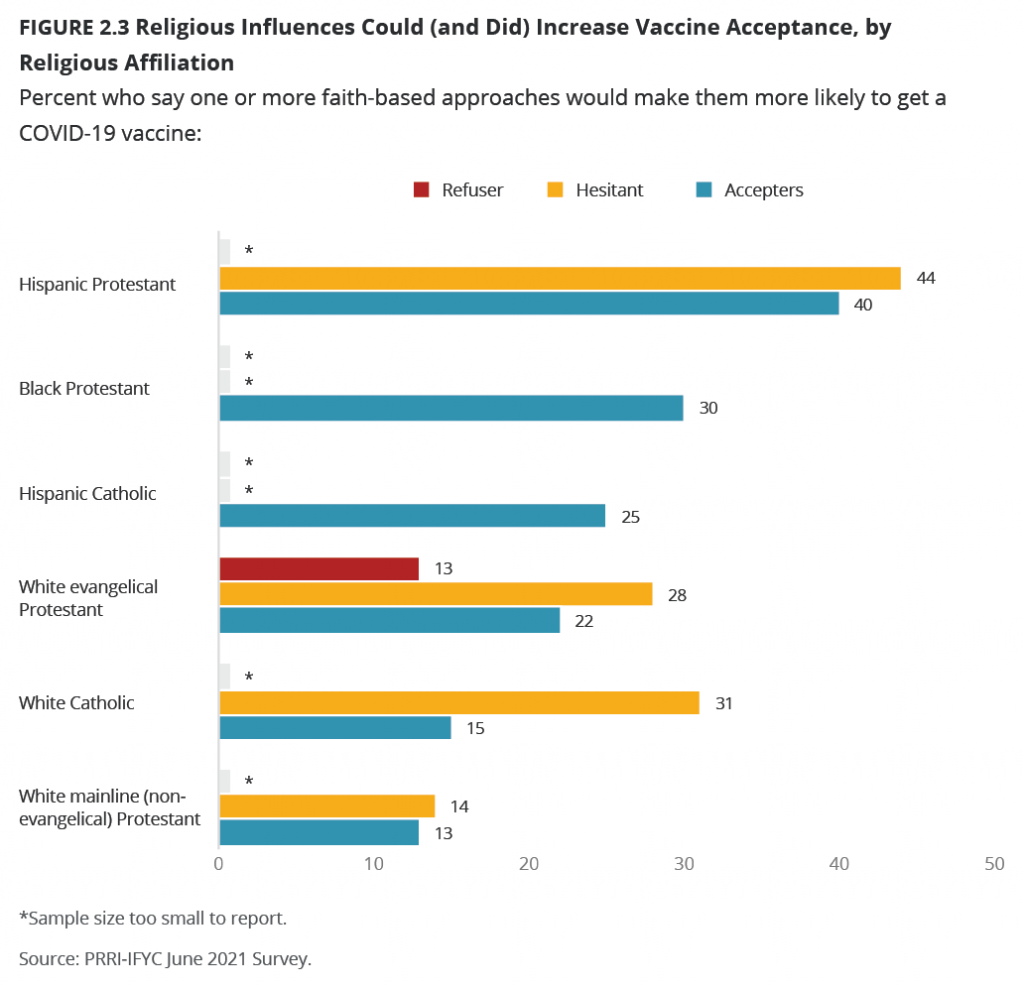

- A majority of Hispanic Protestants who are vaccinated and attend religious services (54%) say one or more faith-based approaches encouraged them to get vaccinated. More than four in ten vaccine hesitant Hispanic Protestants (44%) say one or more faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.

- Almost one-third of vaccine hesitant white evangelical Protestants who attend services (32%) say one or more faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated. Among those who are vaccinated and attend services, more than one in four white evangelical Protestants (26%) say one or more faith-based approaches encouraged them to get vaccinated.

- White Catholics who are vaccine hesitant have become more than twice as likely to say one or more faith-based approaches could sway them (31%) than they were in March (15%). Of those who are vaccinated, 15% of white Catholics, and 25% among those who attend religious services, say one or more faith-based approaches mattered.

Opportunities for increasing vaccine uptake are evident in substantial portions of Black, Hispanic, and younger Americans reporting logistical barriers to getting vaccinated.

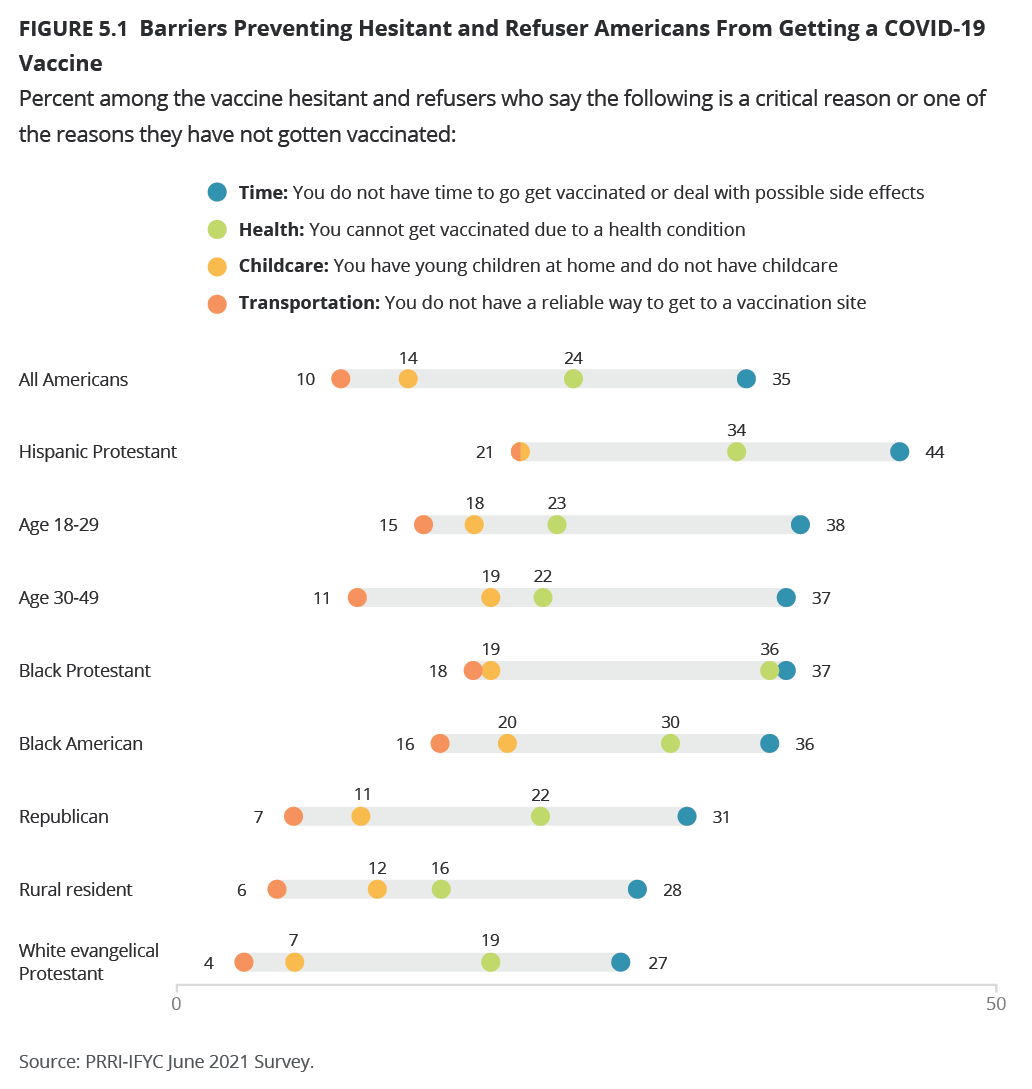

- More than four in ten Hispanic Protestants (44%) say that having time to get vaccinated or deal with the possible side effects is a critical reason (22%) or one of the reasons (22%) they have not gotten vaccinated yet. More than one-third of Americans ages 18–29 (38%), 30–49 (37%), Black Protestants (37%), and Black Americans (36%) say the same.

- Black Protestants are most likely to report that a health condition is a critical reason (18%) or one of the reasons (18%) they have not gotten vaccinated. About one-third of Hispanic Protestants (34%) also report that health is a critical reason or one of the reasons they have not gotten vaccinated.

- Hispanic Protestants are most likely to report that lack of childcare is an issue (21%), but one in five Black Americans (20%) struggle with this as well. The same is true of having reliable transportation: Hispanic Protestants (21%) and Black Protestants (18%) are most likely to say this is a critical barrier or one of the reasons they have not yet gotten vaccinated.

- Across all four barriers, Republicans, rural Americans, and white evangelical Protestants are no more likely than all Americans to report these as critical challenges or reasons they have not gotten vaccinated, despite their lower-than-average vaccination rates.

Partisanship, education, and age remain key dividing factors in vaccine attitudes.

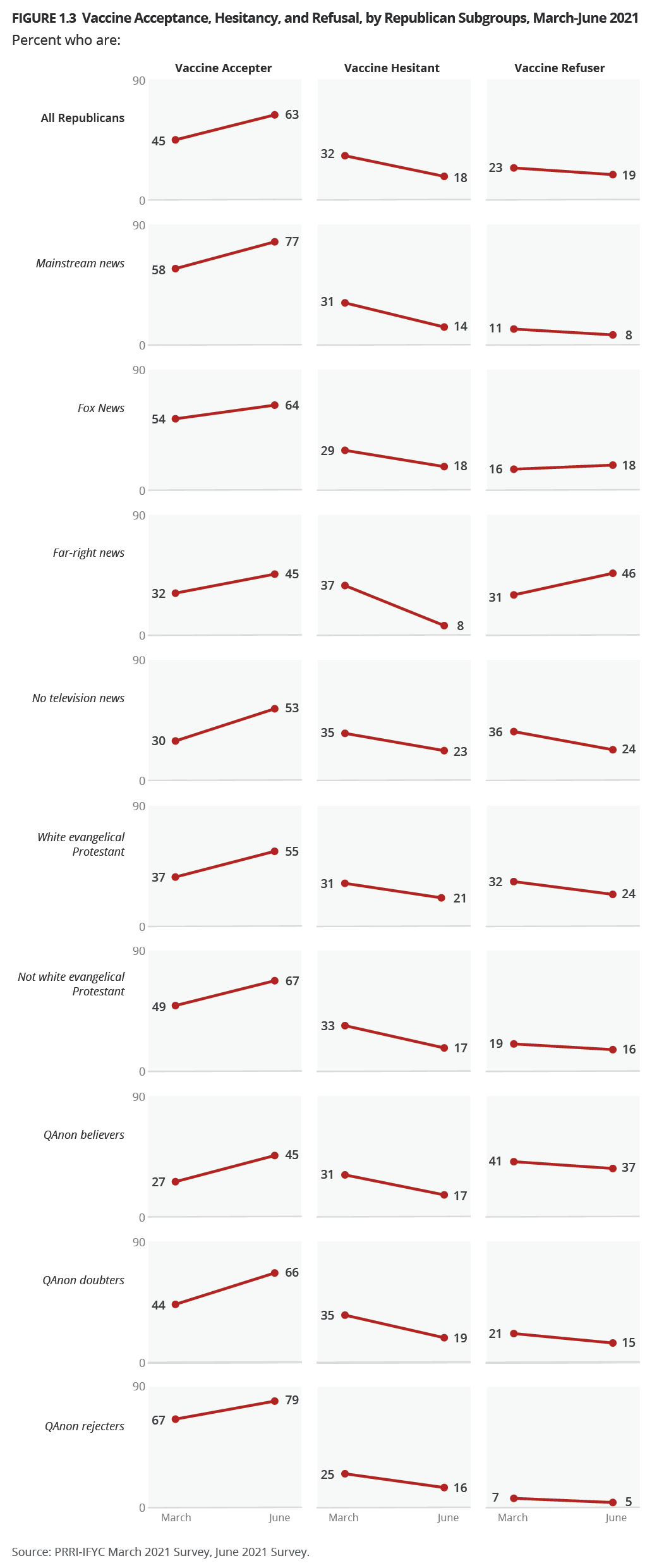

- Republicans remain less likely than independents or Democrats to be vaccine accepters but have increased from 45% accepter in March to 63% in June, a larger gain than independents (58% to 71%) or Democrats (73% to 85%).

- However, Republicans remain divided by what media they trust. Those who most trust far-right news outlets (46%) have become more likely than they were in March (31%) to refuse vaccination.

- Majorities of Americans without college degrees in all race and ethnic groups are vaccine accepters, whereas most were below 50% accepter in March. Black and Hispanic Americans without four-year degrees have increased most—about 20 percentage points (40% in March to 59% in June for Black Americans; 49% in March to 69% in June for Hispanic Americans).

- Republicans, Americans under age 50, and rural Americans remain among the most likely to be hesitant or refusers, but about one in five of those who are vaccinated in each of these groups—those under 50 (19%), Republicans (20%), and rural Americans (20%)—say one or more of these faith-based approaches helped convince them to get vaccinated.

Vaccine Acceptance, Hesitancy, and Refusal

As of the end of June, more than seven in ten Americans (71%) are vaccine accepters, including two-thirds of Americans (67%) who report that they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine and an additional 4% who say they will get vaccinated as soon as possible. The current levels of vaccine uptake represent a marked 13-point increase compared to March, when 58% of Americans were vaccine accepters. Notably, in March, only 32% of the public had received at least one dose of the vaccine, while 26% planned to get vaccinated as soon as possible. Today, almost all of those who want to get vaccinated have received at least one dose of a vaccine.

As the proportion of Americans who are vaccine accepters has increased, vaccine hesitancy has decreased. Less than one in five Americans (15%) are vaccine hesitant, including 10% who say they will wait to see how vaccines are working for others and 5% who will only get vaccinated if it is required for work, school, or other activities. In March, nearly twice as many were vaccine hesitant, including 19% who were in the “wait and see” category and an additional 9% who said they would only get vaccinated if it were required for certain activities. Vaccine refusers—those who say they definitely will not get a vaccine—comprise 13% of Americans, which is relatively unchanged from March (14%).

Seven in ten (71%) say that a family member has received at least one dose of a vaccine, a majority (56%) say a close friend has received at least one dose, and half (50%) say an acquaintance has received at least one dose. Just four percent of Americans report that they do not know anyone who has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. However, the family and friendship networks of those who are vaccinated and those who are not look significantly different. Among those who are vaccinated, 77% report that a family member has received at least one dose of a vaccine, two-thirds (67%) report that a close friend has received at least one dose, and a majority (57%) report that an acquaintance has received at least one dose. By contrast, among those who are not vaccinated, 61% report that a family member has received at least one dose of a vaccine, one-third (33%) report that a close friend has received at least one dose, and 35% report that an acquaintance has received at least one dose.

Religious Affiliation and Vaccine Hesitancy

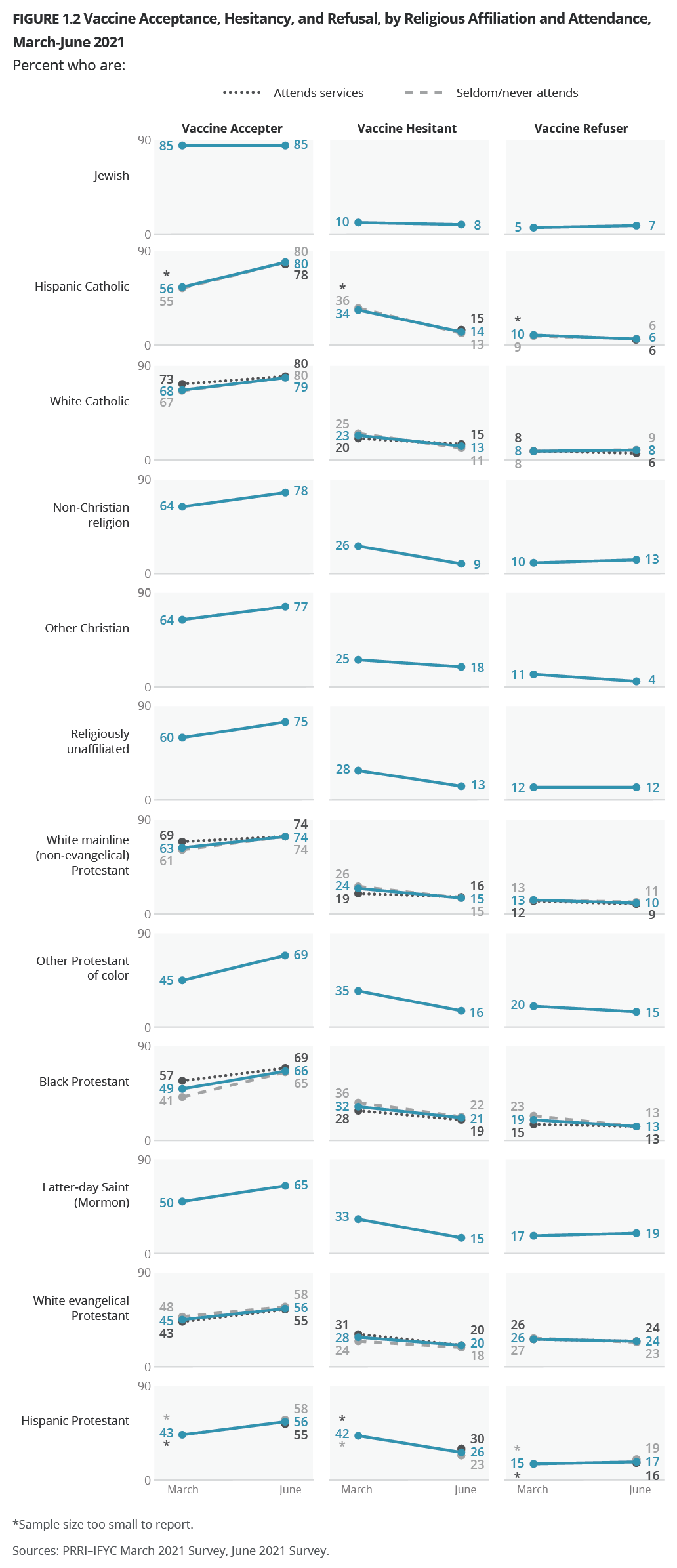

Among religious groups, patterns of vaccine uptake have remained largely consistent between March and June. Jewish Americans are most likely to be vaccine accepters (85%), but, notably, they have not increased in likelihood since March (85%), even though all other religious groups have seen at least 10-percentage-point increases in acceptance.

Hispanic Catholics have increased most in vaccine acceptance, from 56% in March to 80% in June. Nearly eight in ten white Catholics (79%) are also vaccine accepters, up from 68% in March. Other Protestants of color (69%) increased by a similar amount from 45% in March. Other non-Christians (78%), other Christians (77%), the religiously unaffiliated (75%), and white mainline Protestants (74%) are also above the 70% mark, with increases of 11 to 15 percentage points in each group.[1] Black Protestants (66%) and Latter-Day Saints (Mormons) (65%) fall around the two-thirds mark, with similar increases since March. Hispanic Protestants and white evangelical Protestants remain the least likely religious groups to be vaccine accepters (56% for both groups), but both groups nonetheless saw double-digit increases in acceptance since March (43% and 45%, respectively).[2]

Changes in acceptance have come from decreases in hesitancy. The proportions of religious groups that say they will not get vaccinated have held steady since March. The highest refusal rate is still among white evangelical Protestants (24%).

Interestingly, frequency of church attendance does not appear to have the same impact on vaccine acceptance as it did in March. Currently, there are no meaningful differences across religious groups between those who attend religious services at least a few times per year and those who seldom or never attend services. This shift is notable particularly for white evangelical Protestants. In March, more frequent church attenders were less likely than infrequent church attenders to be vaccine acceptant, but that gap has closed in the June data.

Party Affiliation and Vaccine Hesitancy

While Republicans have increased significantly in vaccine acceptance—from 45% in March to 63% in June—they remain significantly more likely than Democrats or independents to say that they will refuse to get vaccinated against COVID-19. About one in five Republicans are either vaccine hesitant (18%, down from 32% in March) or vaccine refusers (19%, down slightly from 23% in March). By contrast, more than eight in ten Democrats (85%) are vaccine accepters, up from 73% in March. Only 10% of Democrats remain hesitant (down from 21%) and only 4% are refusers (similar to the 6% recorded in March). Independents have increased their acceptance, from 58% in March to 71% in June, while decreasing in hesitancy, from 29% in March to 17% in June, and holding steady in refusals (13% in March, compared to 12% in June).

Divisions persist among Republicans by which television news outlets they trust most. Republicans who most trust mainstream news outlets are more likely than Americans on average to be vaccine accepters (77%), while 14% are hesitant and 8% say they will not get vaccinated. More than six in ten Republicans who most trust Fox News report being vaccine accepters (64%), while 18% are hesitant and 18% refuse to get vaccinated. Republicans who do not trust TV news sources are less likely to say they are vaccinated (53% are vaccine accepters, 23% are hesitant, and 24% refuse). Notably, less than half of Republicans who most trust far-right news (45%) are vaccine accepters, while 8% are hesitant and 46% say they refuse to get vaccinated. Republicans who most trust far-right news outlets have become more likely than they were in March (31%) to refuse vaccination.

White evangelical Protestant Republicans are less likely to be vaccine acceptant than Republicans of other religious affiliations (55% vs. 67%, respectively). One in five white evangelical Protestant Republicans are vaccine hesitant (21%), while around one in four (24%) say they will not get vaccinated. Republicans of other religions are slightly less likely to be vaccine hesitant (17%), and less than two in ten (16%) say they will not get vaccinated.

Republicans’ openness to QAnon conspiracy thinking also drives vaccine hesitancy.[3] Less than half of QAnon believers say they have gotten at least one vaccine dose or will get one as soon as possible (45%), while 17% are hesitant and nearly four in ten (37%) say they will not get vaccinated. Among QAnon doubters, two-thirds are vaccine accepters (66%), while around two in ten are hesitant (19%) and 15% are vaccine refusers. Among Republicans who reject core QAnon beliefs, more than three in four (79%) are vaccine acceptant, while 16% are hesitant and just 5% are refusers.

Demographics and Vaccine Hesitancy

Race and Ethnicity

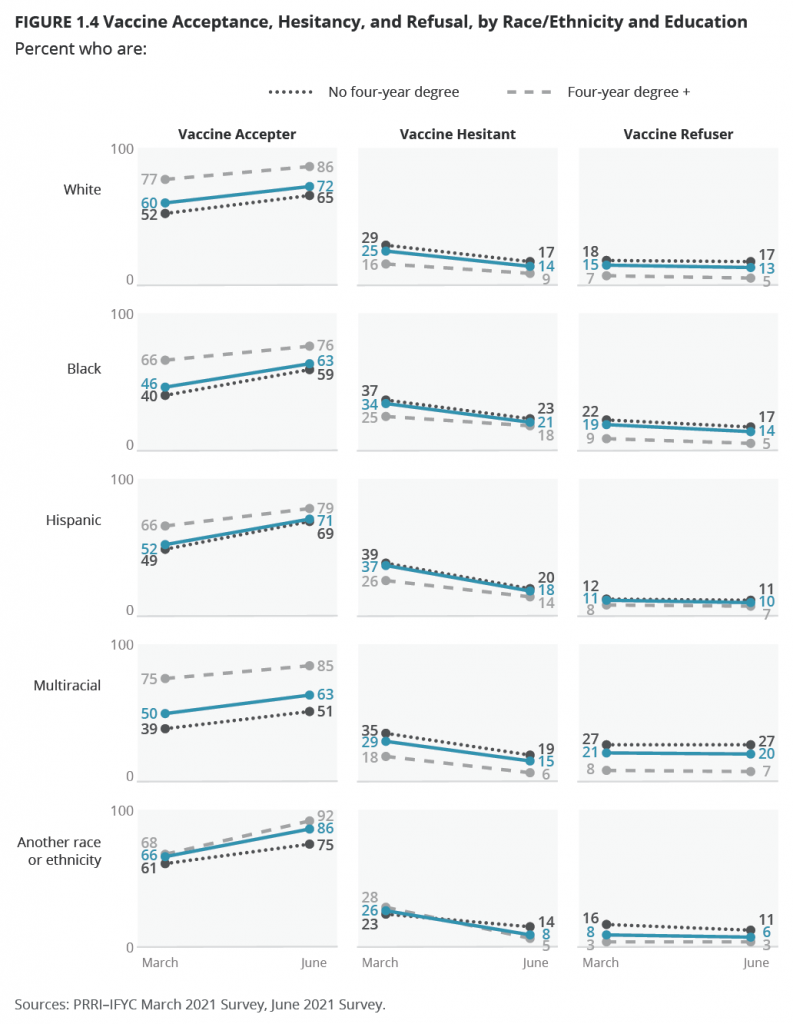

Vaccine acceptance has increased since March among Americans of all races and ethnicities, while hesitance has declined. The largest increases in acceptance are among Hispanic Americans (71%, up from 52% in March) and Black Americans (63%, up from 46% in March), followed by Americans of other races (86%, up from 66% in March), white Americans (72%; up from 60% in March), and multiracial Americans (63%, up from 50% in March).[4] The share of each racial or ethnic group who refuse to get vaccinated has remained relatively similar. One in five multiracial Americans (20%) say they will not get vaccinated, along with 14% of Black Americans, 13% of white Americans, 10% of Hispanic Americans, and 6% of Americans of other races.

Education Level

Americans of all levels of formal education are similarly more likely to be vaccine acceptant now than they were in March. Americans with high school degrees or less have shifted most (61%, up from 45%), though movement is relatively similar across other groups: Americans with some college experience but no degrees have increased to 70%, from 56% vaccine acceptant in March; Americans with four-year degrees have increased to 80%, from 70% in March; and Americans with postgraduate degrees have increased to 92%, from 79% in March.

The education gap is largest among multiracial Americans, with 85% of multiracial Americans with at least four-year college degrees saying they have gotten at least one dose of a vaccine or saying they will as soon as they can, compared to 51% of those with less than a four-year degree. The same education gap is present among white Americans (86% vs. 65%), Black Americans (76% vs. 59%), and Americans of other races (92% vs. 75%). The education gap among Americans of other races or ethnicities has widened slightly. In March, 68% of those with four-year college degrees were vaccine acceptant, compared to 61% of those with less than a four-year degree. Those shares have grown to 92% and 75%, respectively.

Age

Younger Americans continue to be less likely than older Americans to say they have gotten at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or that they will get one as soon as possible. Americans over age 65 are most likely to be vaccine acceptant (86%, an increase from 79% in March), and less than one in ten are vaccine hesitant (6%) or say they will not get vaccinated (7%). Around three in four Americans ages 50–64 are vaccine acceptant (74%, up from 58%), while around one in ten are hesitant (14%) or refusers (11%). Younger Americans ages 30–49 and ages 18–29 are less likely to be acceptant (64% for both groups; an increase from 48% and 49%, respectively). About one in five of those ages 30–49 and 18–29 are hesitant (18% and 22%, respectively), and 17% of those ages 30–49 and 13% of those ages 18–29 say they will not get vaccinated.

Gender

As in March, men continue to be slightly more likely than women to have gotten a dose of a vaccine or to say they will get one as soon as possible. However, women have seen a slightly larger increase in acceptance since March (to 69% from 54%) than men (to 73% from 61%).

Community Type

Americans in urban (75%) and suburban areas (73%) remain more likely than those who live in rural areas (59%) to say they have gotten at least one dose of a vaccine or will get vaccinated as soon as possible. All types of areas have increased their vaccine acceptance at about the same rate compared to March (60%, 59%, and 46%, respectively). Rural residents are more likely to say they will refuse to get a vaccine (20%) than suburban (12%) and urban (9%) residents, which is mostly unchanged since March (24%, 13%, and 11%, respectively).

Vaccinations for Children

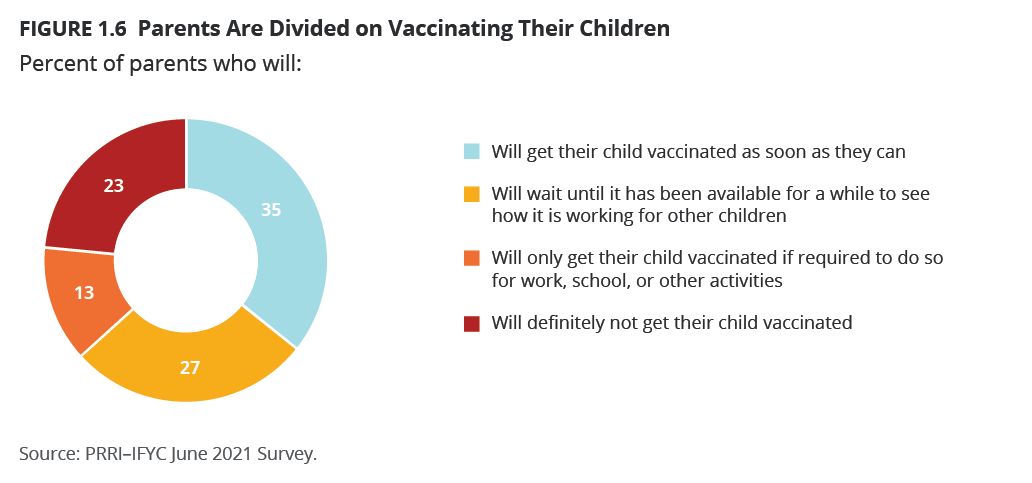

Parents are much more hesitant about getting their children vaccinated against COVID-19 than they are about getting vaccinated themselves. Slightly more than one-third of Americans who are parents of children under age 18 (35%) say they will get their children vaccinated as soon as they can. Four in ten parents are hesitant to get their children vaccinated (40%), including slightly more than one in four parents (27%) who say they will wait to see how vaccines are working for other children and 13% who say they would only get their children vaccinated if it were required for work, school, or other activities. Around one in four parents of children under 18 say they will not get their children vaccinated (23%).

Patterns in acceptance, hesitancy, and refusal to get children vaccinated generally mirror the same patterns across demographic groups as self-reported vaccination status, albeit with greater rates of hesitancy and refusal for children. Half of Democrats (49%) are vaccine acceptant for their children, while 37% are hesitant and 12% say they will not get their children vaccinated. More independents are undecided, with 33% acceptant, 47% hesitant, and 19% refusing vaccines when it comes to their children. Republicans are least likely to be acceptant (24%), while 38% are hesitant and more than one-third (36%) say they will not get their children vaccinated.

Not surprisingly, the approaches parents are taking with their children generally mirror their views about getting vaccinated themselves; however, even vaccine acceptant parents are more hesitant when it comes to their children. Among those who are vaccine acceptant, 56% are vaccine acceptant for their children, 36% are hesitant, and 7% say they will not get their children vaccinated. Among vaccine hesitant parents, just 3% will get their children vaccinated as soon as possible, 81% are hesitant to get their children vaccinated, and 13% say they will not get them vaccinated. Vaccine rejecters almost universally will not get their children vaccinated (94%).

White evangelical Protestants (18%) and Hispanic Protestants (27%) are the least likely religious groups to say they have gotten their children vaccinated or will get their children vaccinated as soon as possible. White evangelical Protestants are less likely to say they are hesitant to get their children vaccinated (36%) than to say they will not get their children vaccinated (42%), while Hispanic Protestants are much more likely to be hesitant (52%) than to refuse vaccines for their children (19%). Around one-third of white mainline Protestants (33%), Black Protestants (35%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (35%) are vaccine acceptant for their children. Four in ten white Catholics (40%) and around half of Hispanic Catholics (48%) say they have or will get their children vaccinated.

Americans of other races are most likely to say they will get their children vaccinated as soon as they can (56%), compared to much smaller shares of Hispanic Americans (39%), multiracial Americans (35%), white Americans (32%), and Black Americans (26%).

Parents with high school degrees or less are half as likely as those with postgraduate degrees to say they will get their children vaccinated as soon as possible (26% vs. 52%), while those with some college experience but no degree (31%) and those with four-year college degrees (45%) fall in between. Parents with a high school degree or less (29%) or some college (26%) are almost twice as likely as those with four-year degrees (14%) or postgraduate degrees (13%) to say they will not get their children vaccinated.

Faith-Based Approaches to Encouraging Vaccination

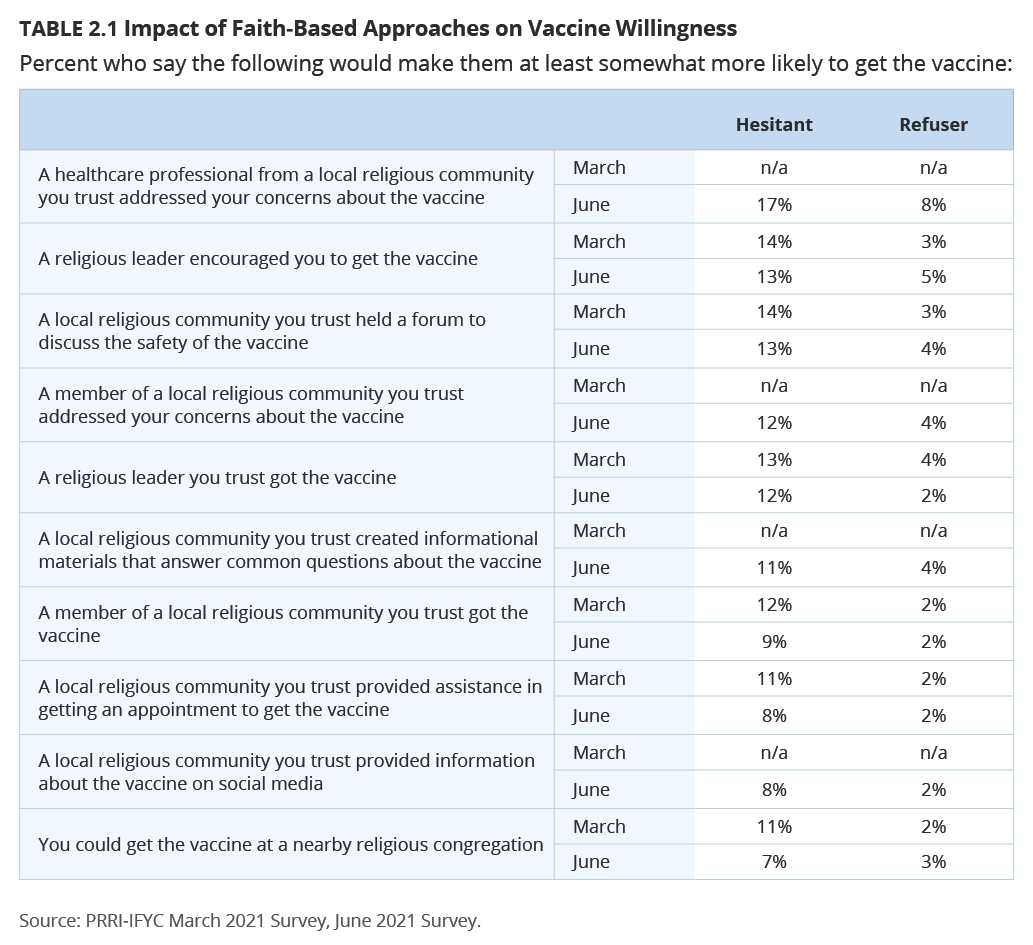

Among Americans who are hesitant about getting vaccinated, approximately one in four (26%) indicate that one or more faith-based approaches would make them at least somewhat more likely to get vaccinated, identical to the 26% who said the same in March. Even among vaccine rejecters, 12% say one or more faith-based approaches might sway them, an increase from 7% in March, although the June survey tested four additional approaches.

The individual faith-based scenarios explored in the survey and their impact on improving vaccine uptake are summarized in Table 2.1.

The influences of close friends, family members, and trusted healthcare providers also continue to show promise for encouraging people to get vaccinated, although the influence of these groups has waned since March. For example, 27% of those who are hesitant to get vaccinated say a close friend or family member getting a vaccine would make them more likely to get a vaccine (compared to 40% among the hesitant group in March), and only 4% of refusers say the same (compared to 7% in March). One-third of those who are hesitant (33%), down from four in ten (40%) in March, say a doctor or healthcare provider getting a vaccine would make them more likely to get a vaccine, compared to 7% of refusers (unchanged from 9% in March).

Among groups with strong attachments to religion, faith-based approaches rival the effects of family members and healthcare providers. Among those who attend religious services at least occasionally and are vaccine hesitant, 38% would be somewhat or much more likely to get vaccinated with one or more of these faith-based approaches (down slightly, from 44% in March), as would 19% of vaccine refusers who regularly attend religious services (increased slightly, from 14% in March). Notably, among those who are already vaccinated and attend religious services at least a few times per year, about one-third (32%) reported that one or more of the faith-based approaches made them more likely to get vaccinated.

The impact is smaller among those who seldom or never attend religious services: 19% of this group who are vaccine hesitant indicate one or more of the religious scenarios would make them more likely to get vaccinated, along with 7% of this group who are vaccine refusers.

Religious groups with high levels of vaccine hesitancy or refusal are also the most likely to say they would be influenced by faith-based approaches. More than four in ten Hispanic Protestants who are hesitant to get vaccinated (44%) say one or more of these faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get vaccinated.[5]

White evangelical Protestants who remain hesitant in June are less likely than this group was in March to respond to these faith-based approaches: 28% say one or more would make them more likely to get vaccinated, compared to 38% in March. Among refusers, 13% report one or more of these faith-based strategies could work, an increase from 4% in March. Vaccine-hesitant white evangelical Protestants who attend religious services at least a few times per year have similarly declined in their responses to these approaches: 32% say one or more approaches would move them, compared to nearly half (47%) in March. It is likely that this decline is due to the significant portion of vaccine hesitant white evangelicals who nonetheless got vaccinated between March and June. Overall white evangelical Protestant hesitancy declined, from 28% in March to 20% in June, offset by an increase in those reporting they have gotten vaccinated. White evangelical Protestants who are vaccine refusers and attend religious services are significantly more likely to report that one or more of these approaches could move them (17%) than they were in March (7%).

White Catholics who are vaccine hesitant have become more than twice as likely to say one or more faith-based approaches could sway them (31%) than they were in March (15%). The proportion of vaccine hesitant white mainline Protestants (14%) who say one or more of the faith-based approaches would make them more likely to get a vaccine has not changed substantially since March (18%).[6]

Among those who are vaccinated, many Christians of color report that faith-based approaches did matter in their decisions to get vaccinated. Hispanic Protestants (40%) and Black Protestants (30%) are particularly likely to say that one or more of these faith-based approaches helped convince them to get a vaccine. In fact, a majority of vaccinated Hispanic Protestants who attend religious services (54%) report this, as do more than four in ten vaccinated Black Protestants who attend religious services (42%). One in four Hispanic Catholics who are vaccinated (25%) say one or more of these faith-based approaches helped convince them, and that increases to 45% among those who attend services.[7] White evangelical Protestants (22%), white Catholics (15%), and white mainline Protestants (13%) who are vaccinated are less likely to report that faith-based approaches made a difference, but those numbers increase to one in four white evangelical Protestants (26%) and white Catholics (25%) who attend religious services, and 19% among white mainline Protestants who attend services.

Notably, faith-based approaches to vaccine uptake also have a significant effect on some non-religious groups that have significant levels of vaccine hesitancy. Among all Americans under age 50 who are vaccine hesitant, 26% say faith-based approaches could help (similar to 25% in March), despite being less likely than older Americans to affiliate with a religion and attend services. Among those who are under 50 and vaccine refusers, 13% say faith-based approaches could help convince them to get vaccinated (compared to 8% in March).

One in five Republicans who are vaccine hesitant (21%) say faith-based interventions could move them toward vaccination, only a small decrease compared to the 26% who said the same in March. Republicans who are vaccine refusers are almost twice as likely now to say one or more of these approaches could work (13%) than they were in March (7%).

More than one in four rural Americans who are vaccine hesitant (27%) say faith-based approaches could work, compared to only 5% of rural Americans who are vaccine refusers. These proportions are mostly unchanged since March (24% and 5%, respectively). About one in five of those who are vaccinated in each of these groups — people under 50 (19%), Republicans (20%), and rural Americans (20%) — say one or more of these faith-based approaches helped convince them to get vaccinated.

Three in ten parents with children under the age of 18 who are hesitant to get vaccinated (30%) indicate one or more faith-based approaches could help sway them, and among vaccinated parents, 22% said one or more faith-based approaches helped convince them.

The Role of Religion and Religious Leaders in Vaccine Attitudes

Vaccination As an Example of Loving Your Neighbor

A majority of Americans (56%) agree with the statement “Because getting vaccinated against COVID-19 helps protect everyone, it is a way to live out the religious principle of loving my neighbors,” while 42% disagree with the statement. Agreement with this idea is similar to what was reported in March (53% agree vs. 44% disagree). While agreement with this idea is the same as was reported in March among vaccine accepters (70% in both March and June) and refusers (14% in March and 11% in June), notably, among the vaccine hesitant, it went down, from 40% in March to 29% in June.

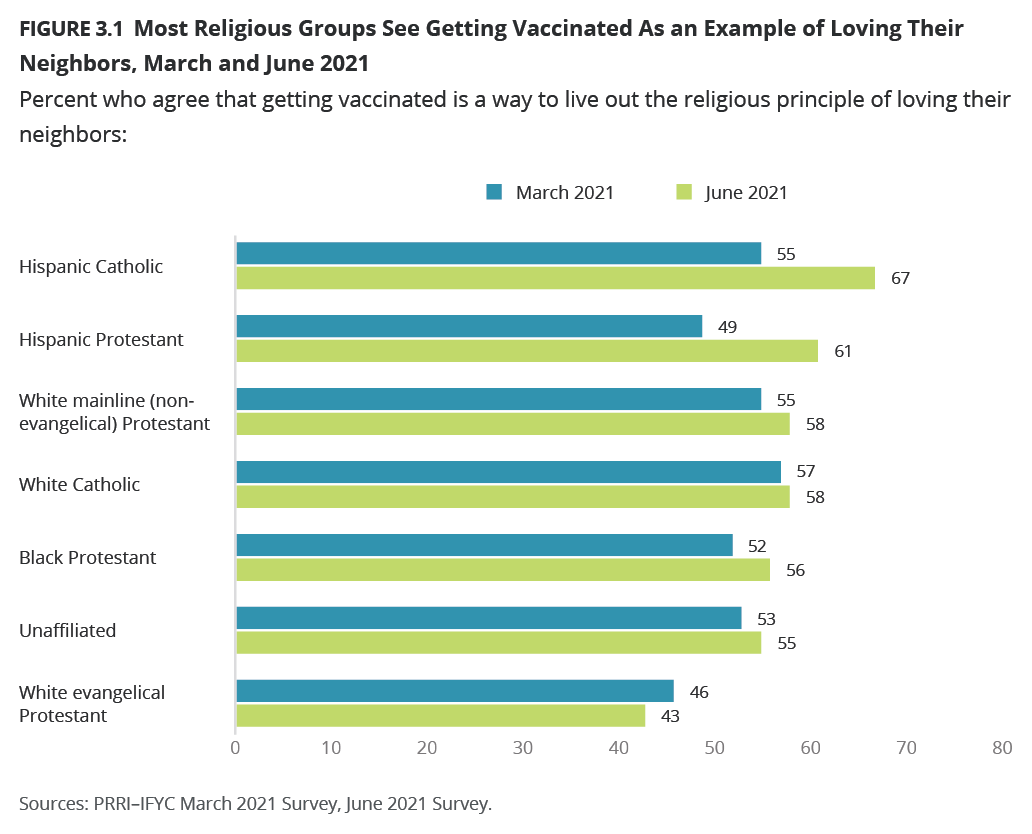

With the exception of white evangelical Protestants (43%), majorities of all major religious groups agree that getting vaccinated is a way to live out the religious principle of loving their neighbors. Two-thirds of Hispanic Catholics (67%) as well as majorities of Hispanic Protestants (61%), white mainline Protestants (58%), white Catholics (58%), Black Protestants (56%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (55%) agree.[8] Compared to March, Hispanic Catholics (55% in March vs. 67% in June) and Hispanic Protestants (49% in March vs. 61% in June) have become more likely to agree with this question.

Seven in ten Americans of other races (70%), compared to 64% of Hispanic Americans, 56% of Black Americans, 52% of white Americans, and 41% of multiracial Americans agree that getting vaccinated is a way to show love for their neighbors.[9] Hispanic Americans are notably more likely to agree with this statement today than they were in March (54%).

There are clear educational gaps over whether Americans agree that getting vaccinated is a way to express love for their neighbors. Americans with high school degrees (50%) and some college (51%) are less likely than those who have four-year college degrees (64%) and those who have postgraduate degrees (72%) to agree. Interestingly, Americans with high school degrees are more likely today to agree with this statement than they were in March (43%).

Americans over age 65 (67%) are more likely than younger Americans to agree that getting vaccinated is a form of loving their neighbors. Around half of Americans ages 18–29 (54%), ages 30–49 (51%), and ages 50–64 (54%) agree.

Religious Leaders As a Source for Vaccine Information

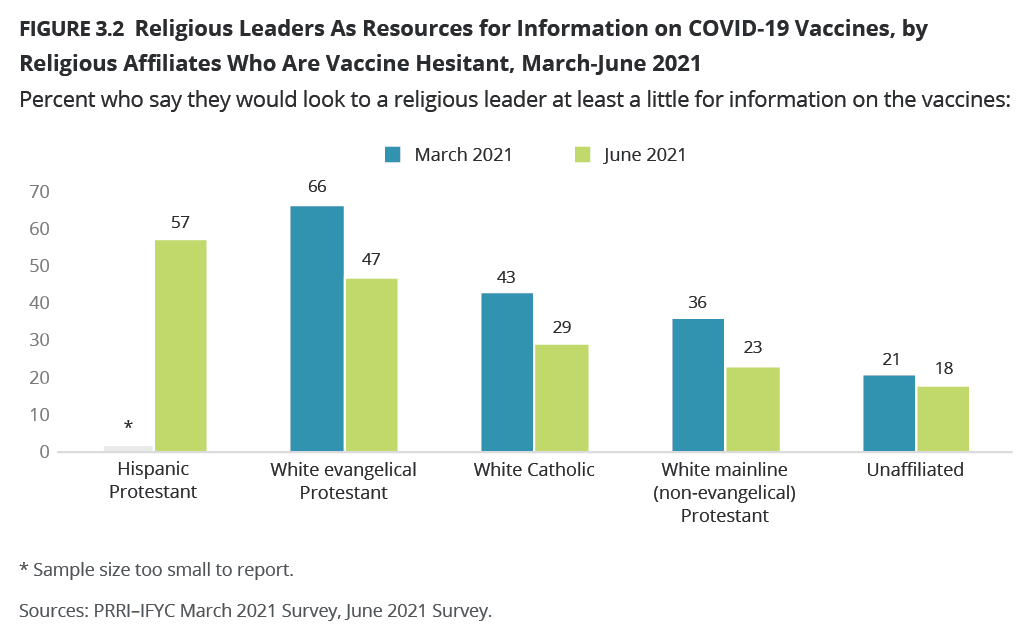

About one in five Americans (17%) say they would, or did, in the case of those who have already received a vaccine, look to a religious leader for information when deciding whether to get a COVID-19 vaccine. Americans are notably less likely to turn to religious leaders for information today than they were in March (32%). The vaccine hesitant (36%) are more likely than vaccine refusers (24%) to turn to religious leaders for information, but both numbers are notably down from their March levels (46% and 34%, respectively), likely due to those who were hesitant and even some refusers who were more amenable to vaccination in March converting to the accepter category in June.

About four in ten Black Protestants (37%), Hispanic Protestants (37%), Mormons (37%), and other Christians report they would or did look to religious leaders for information about the vaccines at least a little. Nearly three in ten white evangelical Protestants (28%) and about two in ten other Protestants of color (22%), Hispanic Catholics (21%), and members of other non-Christian religions (19%) also report the same. White mainline Protestants (12%), white Catholics (12%), Jewish Americans (12%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (6%) are the least likely to report that they would or did look to religious leaders for information about the vaccines at least a little. With the exception of Jewish Americans and Mormons, every other religious group is notably less likely to turn today to religious leaders for information than they were in March.

Among key groups who are most vaccine hesitant, however, religious leaders could still be effective messengers for vaccine acceptance. Nearly six in ten Hispanic Protestants (57%) and nearly half of white evangelical Protestants (47%) who are vaccine hesitant report they would turn to religious leaders for information about the vaccines at least a little. Additionally, 29% of white Catholics, 23% of white mainline Protestants, and 18% of religiously unaffiliated Americans who are vaccine hesitant would turn to religious leaders for information on vaccines at least a little.[10] With the exception of Hispanic Protestants and religiously unaffiliated Americans, vaccine hesitant members of religious groups are less likely to turn to religious leaders for information today than they were in March.

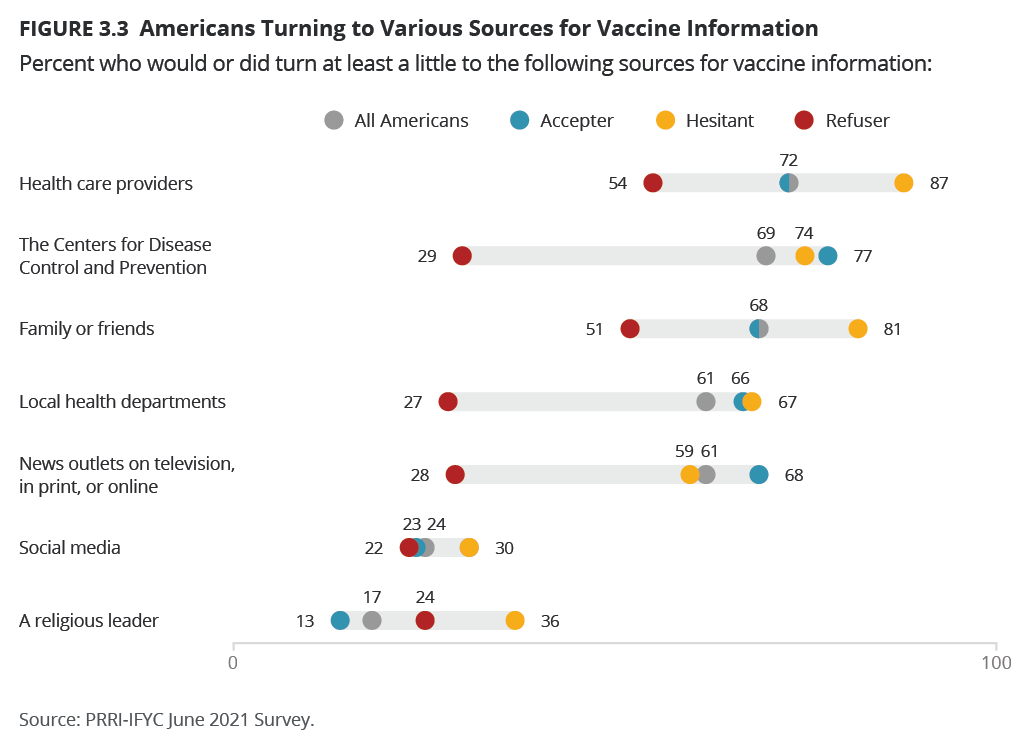

Majorities of Americans report they are likely to turn to healthcare providers (72%), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (69%), family or friends (68%), local health departments (61%), and news outlets on television, in print, or online (61%) at least a little for information about vaccines. With the exception of the CDC and news outlets, across all these sources, the vaccine hesitant are more likely than refusers, accepters, and all Americans to trust these sources for vaccine information at least a little. One in four Americans (24%) turn to social media at least a little for information about vaccines and are the least likely to show notable differences among refusers (22%), accepters (23%), all Americans (24%), and the vaccine hesitant (30%).

Vaccination Requirements

Vaccination Requirements for Public Activities

A majority of Americans (56%) support requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination to participate in certain activities, such as travel, work, or school. More than four in ten Americans (42%) oppose requiring proof of vaccination to take part in such activities. Vaccination status is the biggest opinion divider for this question. A large majority of those who are vaccine accepters (73%) support requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination for certain activities, although, notably, more than one in four (27%) oppose it. Those who are hesitant to get vaccinated are substantially less likely to support requiring proof of vaccination (24%), and nearly three in four (74%) oppose it. Few vaccine refusers support requiring such proof (7%), and the vast majority (92%) oppose it.

More than three in four Democrats (77%) support requiring a vaccine passport for participating in certain activities, as do a majority of independents (56%). Unsurprisingly, Republicans (37%) are least likely to support COVID-19 vaccine requirements, given their lag in vaccine acceptance. Approximately six in ten Republicans (63%) oppose these requirements.

Non-Christian and Christian groups of color are more likely than white Christians to support vaccination requirements for certain activities. Seven in ten or more other Christians (72%), Jews (71%), and other non-Christian religious groups (70%) support requiring proof of vaccines for activities like travel, work, or school. Majorities of Hispanic Catholics (67%), religiously unaffiliated Americans (64%), Black Protestants (63%), white Catholics (59%), and other Protestants of color (56%) support requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination, as do slim majorities of white mainline Protestants (52%) and Hispanic Protestants (51%). Latter-day Saints (46%) and white evangelical Protestants (31%) are least likely to support requiring proof of vaccination for certain activities.

Majorities of non-Hispanic white Americans (53%), multiracial Americans (53%), and non-Hispanic Black Americans (58%) support requiring proof of vaccination to participate in certain activities. More than six in ten Hispanic Americans (62%) and three in four Americans of other races (75%) also agree that proof of vaccination should be required.

Generally, Americans with higher levels of education are more likely to favor requiring proof of COVID-19 vaccination. Half of Americans with high school degrees or less educational attainment (50%) and 54% of those with some college education support requiring proof of vaccination for activities like travel, work, or school. That figure jumps to 64% support among those with college degrees, and nearly seven in ten Americans with postgraduate degrees (69%).

Religious Exemptions for COVID-19 Vaccine Requirements

Americans are divided over allowing individuals who would otherwise be required to receive a COVID-19 vaccine to refuse to do so if getting vaccinated would violate their religious beliefs. Currently, a slim majority (52%) favor such religious exemptions, while 46% oppose them. Americans are slightly less likely to favor religious exemptions than they were in March, when 56% favored exemptions and 42% opposed them. In January, 48% favored religious exemptions and 51% opposed them.

Two-thirds of Republicans (69%), compared to less than four in ten Democrats (37%) and 53% of independents, favor religious exemptions for COVID-19 vaccine requirements. Support for religious exemptions has decreased slightly among all three partisan groups compared to March (74% among Republicans, 42% among Democrats, and 56% among independents).

White evangelical Protestants (72%), Latter-day Saints (72%), and other Protestants of color (67%) are most likely to favor religious exemptions to vaccine requirements. Solid majorities of Black Protestants (57%), Hispanic Protestants (57%), white mainline Protestants (55%), and white Catholics (55%) favor allowing people to opt out of vaccinations on religious grounds. Less than half of Jewish Americans (46%), other Christians (45%), non-Christian religious Americans (44%), Hispanic Catholics (41%), and religiously unaffiliated Americans (38%) support these religious exemptions. Since March, support for religious exemptions has decreased among white evangelical Protestants (down from 81%), while support has remained relatively steady among other religious groups.

Just under two-thirds of Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year (64%), compared to just under half of Americans who seldom or never attend services (46%), favor religious exemptions to COVID-19 vaccine requirements. Nearly seven in ten Americans who attend religious services at least once a week or more favor such religious exemptions (69%).

A majority of white Americans (55%) and a slim majority of Black Americans (51%) favor religious exemptions to COVID-19 vaccine requirements. Less than half of multiracial Americans (49%), Hispanic Americans (44%), and Americans of other races (43%) favor religious exemptions. Multiracial Americans have become much less likely to favor religious vaccine exemptions than they were in March (63%), and Black Americans have become somewhat less likely to favor exemptions than they were previously (59%). White Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Americans of other races have not shifted meaningfully in their support for vaccine exemptions since March (59%, 47%, and 45%, respectively). The education gap among white Americans has closed since March, with 56% of white Americans without a four-year college degree who support religious exemptions (down from 64%), and 53% of white Americans with at least a four-year degree (similar to 51% in March) who say the same.

Religious Exemptions for COVID-19 Vaccine Requirements for Children

More than four in ten Americans (42%) agree that children should be allowed to attend public school without receiving required vaccines if they have religious objections. In comparison, nearly six in ten Americans (57%) do not support religiously based vaccine exemptions. These percentages have shifted considerably since January 2021, when more than one in four Americans (27%) supported religiously based vaccine refusals, while nearly three in four Americans (73%) opposed such exemptions. A reason for the jump in support for religiously based vaccine refusals could be that the recent rollout of the COVID-19 vaccines for school-aged teens was top of mind for respondents in June, whereas questions of COVID-19 vaccine requirements for children were not prevalent in January, even though the question did not specify any particular vaccine.

Republicans are more likely to support religiously based vaccine refusals for public school children than independents and Democrats are. A majority of Republicans (58%) support the refusals, while more than four in ten independents (41%) and nearly three in ten Democrats (29%) favor them. A substantial majority of Democrats (70%) oppose allowing public school students to refuse required vaccinations on religious grounds.

Majorities of white evangelical protestants (63%) and Mormons (59%) agree that children should be able to attend public school without required vaccines on religious grounds. A majority of Hispanic Protestants (53%) also agree. More than four in ten other Protestants of color (46%), Black Protestants (45%), and white mainline Protestants (44%) support religiously based vaccine exemptions in public schools, as do 40% of white Catholics and Hispanic Catholics. More than one-third of other Christians (35%) and members of other non-Christian religions (36%), as well as 29% of both Jewish Americans and unaffiliated Americans, support religiously based vaccine refusals.

More than four in ten white Americans (43%) and Black Americans (43%) support religiously based vaccine refusals in public schools. Around four in ten Hispanic Americans (40%) and multiracial Americans (39%) also agree. Three in ten Americans of other races (30%) support religiously based vaccine exemptions for public school students.

Less than half of Americans with high school degrees or less and Americans with some college experience (both 45%) support vaccine exemptions for public school students. In comparison, less than four in ten Americans with four-year college degrees (39%) and more than three in ten Americans with postgraduate degrees (31%) agree.

Factors Preventing People From Getting Vaccinated

Concerns About the Safety of the Vaccines

Americans are less worried today about COVID-19 vaccines than they were in March. The proportion of Americans who worried that the long-term effects of the COVID-19 vaccines are unknown dropped more than 10 percentage points, from 58% in March to 47% in June. Americans also expressed less concern that they would experience serious side effects from the vaccines (from 49% in March to 36% in June), that the vaccines are not as safe as they are said to be (from in March 45% to 36% in June), and that the vaccines are not as effective as they are said to be (from 43% in March to 34% in June).

A four-point composite index was created to evaluate Americans’ concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, including the four areas of concern listed above. Each question was combined using an additive scale that was then converted into a four-point scale, where a score of 1 indicates major concerns, 2 indicates moderate concerns, 3 indicates few concerns, and 4 indicates very few concerns about the COVID-19 vaccines. Using this scale, compared to March, major concerns about the vaccines declined, from 23% in March to 18% in June, and moderate concerns declined, from 38% in March to 31% in June, while few concerns went up, from 32% in March to 36% in June, and very few concerns went up, from 7% in March to 15% in June.

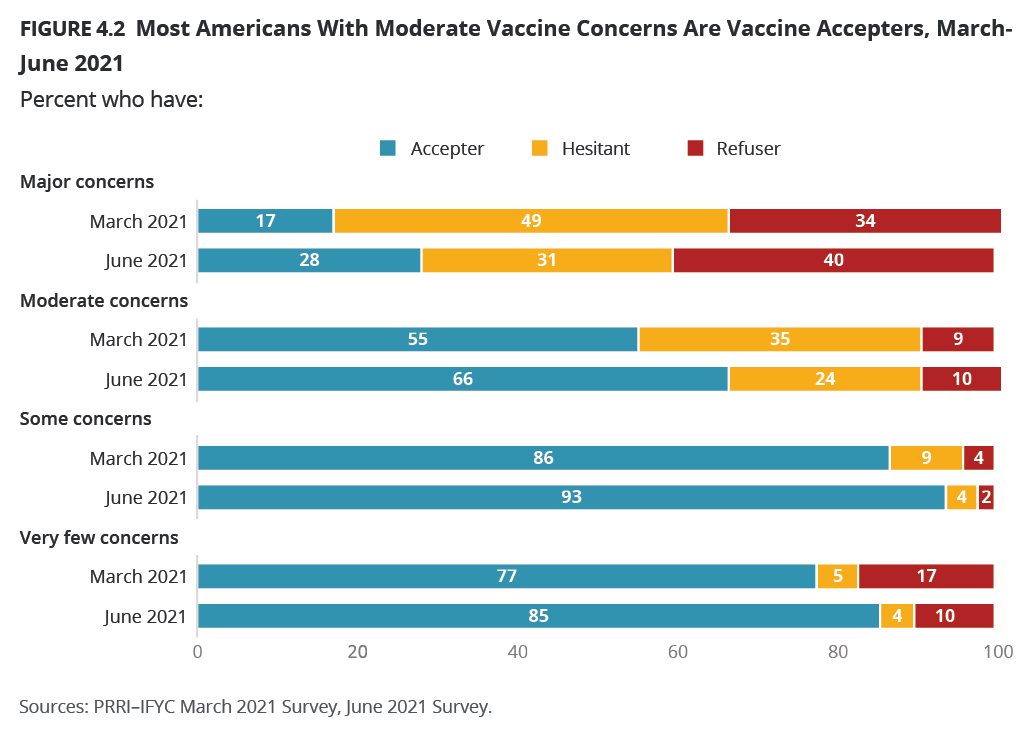

Among those who have major concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, the proportion who are accepters despite those concerns grew, from 17% in March to 28% in June. About three in ten are hesitant to get vaccinated (31%), a significant decline from 49% in March. Notably, among those with major concerns about the vaccines, the proportion who are refusers grew significantly, from 34% to 40% today. Among those with moderate concerns, two-thirds are vaccine accepters (66%), a substantial increase from 55% in March, while about one in four are hesitant (24%), a decline from 35% in March. Only about 10% of those who express moderate concerns are refusers, similar to March (9%). Today, nearly all Americans who express some concerns are vaccine accepters (93%), a notable increase from 86% in March. Only 4% of Americans who express some concerns are hesitant, and 2% are refusers. The share of vaccine accepters who have very few concerns is somewhat smaller (85%), while the share of refusers (10%) is larger than it is among those with some concerns.

A majority of Republicans (54%) have at least moderate concerns about the vaccines, compared to 48% of independents and 43% of Democrats. These proportions are notably lower than they were in March, when two-thirds of Republicans (67%), 60% of independents, and 56% of Democrats expressed similar concerns. Interestingly, concerns about vaccines among Republicans who most trust Fox News declined, from 62% in March to 51% today, while among Republicans who most trust far-right television sources they remain about the same (75% in March and 72% today). About half of Republicans (48%) who most trust mainstream news sources and 60% of those who do not watch television news report moderate or major concerns.

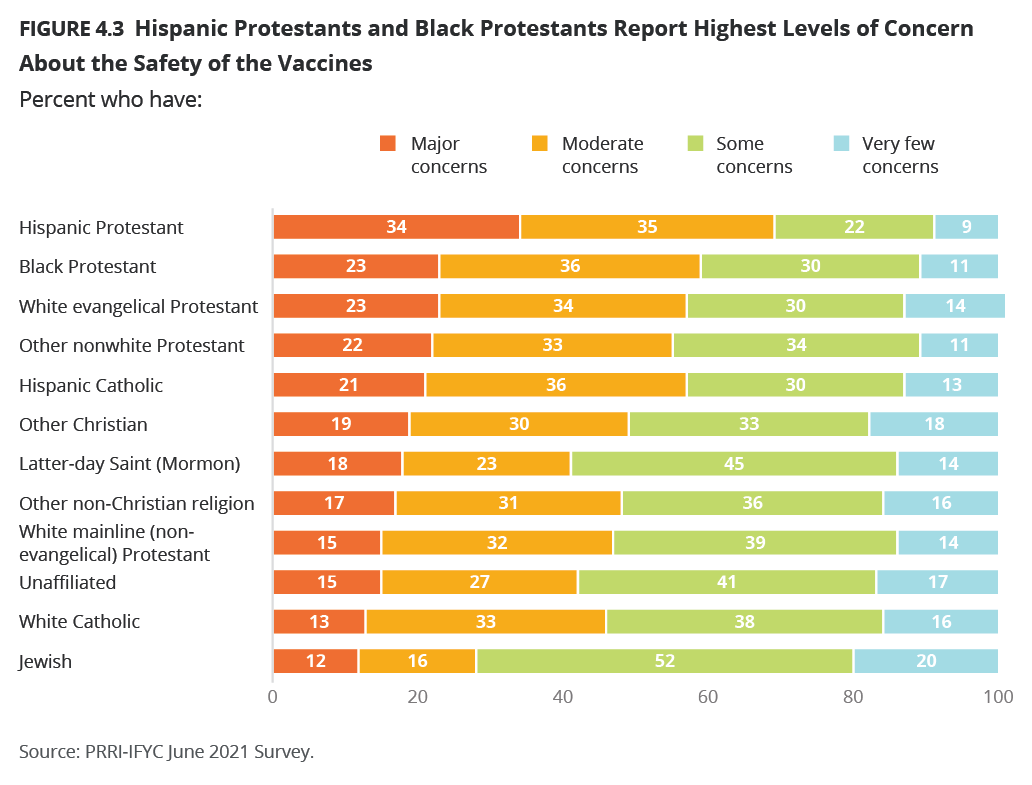

With the exception of Jewish Americans (28%), majorities or a plurality of Americans of all major religious groups report at least moderate concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. Nearly seven in ten Hispanic Protestants (69%) and about six in ten Black Protestants (59%), white evangelical Protestants (57%), Hispanic Catholics (57%), and other Protestants of color (55%) report moderate or major concerns about vaccines. Just under half of members of other Christian groups (49%), members of other non-Christian religions (48%), white mainline Protestants (47%), white Catholics (46%), unaffiliated Americans (42%), and Mormons (41%) express at least moderate concerns about vaccines. Of all religious groups, only Hispanic Catholics (35% in March vs. 21% in June), white evangelical Protestants (30% in March vs. 23% in June), and white mainline Protestants (20% in March vs. 15%) are less likely to express major concerns about vaccines than they were in March.

Nearly six in ten Black Americans (59%) and Hispanic Americans (58%), as well as 52% of multiracial Americans, have at least moderate concerns about vaccines. Less than half of white Americans (46%) and Americans of other races (45%) have at least moderate concerns about vaccines. Notably, concerns about the vaccines have gone down across all race and ethnicity groups since March.

Concerns about COVID-19 vaccines decrease with greater levels of education. Among those with high school degrees or less, nearly six in ten (59%) have at least moderate concerns, including one in four who have major concerns (25%). Nearly half of Americans with some college experience (49%) have at least moderate concerns. By contrast, 44% of Americans with four-year college degrees and only one-third of Americans with postgraduate degrees (32%) have at least moderate concerns. Concerns about the vaccines went down significantly across all education levels since March.

One-third of Americans over age 65 (34%) report at least moderate concerns. Americans ages 30–49 (59%) are the most likely to express concerns about COVID-19 vaccines, compared to Americans ages 18–29 (51%), and Americans ages 50–64 (49%). Women ages 30–49 are notably more likely to express concerns about COVID-19 vaccines than men in the same age category (64% vs. 54%). Again, concerns about the vaccine declined significantly across all age groups since March.

Women are more likely than men to express concerns with COVID-19 vaccines. Nearly six in ten (55%) express at least moderate concerns, including 21% who express major concerns. Less than half of American men (43%) express at least moderate concerns, including 15% who express major concerns. Both women and men are less likely to express concerns with the vaccines today than they were in March.

Skepticism About the Dangers of COVID-19

One in four Americans (24%) say a critical reason they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine is their belief that the seriousness of COVID-19 has been overblown, and an additional 37% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. Nearly four in ten (39%) Americans do not mention this as a reason. Vaccine refusers (37%) are about three times more likely than the vaccine hesitant (13%) to report that the seriousness of COVID-19 has been overblown as a critical reason for not getting a COVID-19 vaccine.

Skepticism is higher among Republicans: 43% who are vaccine refusers and 17% who are hesitant say a critical reason they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine is their belief that the seriousness of COVID-19 has been overblown, compared to 36% of independents who are refusers and 10% who are hesitant, and 23% of Democrats who are refusers and 7% who are hesitant.[11]

There are stark differences by region among vaccine refusers. Half of those who live in the Midwest (50%) report skepticism about the seriousness of the pandemic as a critical reason preventing them from getting the vaccine, compared to 38% who live in the West, 32% who live in the South, and 31% who live in the Northeast.[12]

Lack of Trust in the Healthcare System

About one in four Americans (23%) say a critical reason they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine is that they do not trust the healthcare system, and an additional 39% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. Nearly four in ten Americans (38%) say this is not a reason. Vaccine refusers (36%) are notably more likely than the vaccine hesitant (13%) to report that one critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is their mistrust in the healthcare system.

Americans ages 30–49 who are vaccine refusers are the most likely to mention not trusting the healthcare system as a critical reason they have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine (44%), compared to Americans ages 50–64 (33%), Americans over 65 (28%), and Americans ages 18–29 (24%).[13] Differences among the vaccine hesitant by age group are not significant.

Beyond Hesitancy: Barriers to Getting Vaccinated

Time

Among Americans who are not vaccinated, one in ten (11%) say a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is not having time to go get vaccinated or deal with possible side effects, and an additional 24% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. About 65% of unvaccinated Americans say this is not a reason. About one in ten vaccine refusers (12%) and vaccine hesitant (9%) report that one critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is a lack of time to get vaccinated or deal with possible side effects. Americans with household incomes under $50,000 are about twice as likely as Americans with household incomes over $50,000 to report time as a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine (15% vs. 8%).

Health

One in ten Americans who are not vaccinated (10%) say a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is an existing health condition, and an additional 14% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. About three in four unvaccinated Americans (76%) say this is not a reason. One in ten vaccine refusers (10%) and vaccine hesitant (10%) report that a health condition is a critical reason they are not yet vaccinated.

Childcare

Four percent of Americans who are not vaccinated say a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is a lack of childcare for young children at home, and an additional 10% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. Most unvaccinated Americans (86%) say this is not a reason. Vaccine refusers (4%) are equally likely as the vaccine hesitant (5%) to report that a lack of childcare is a critical reason they have not gotten vaccinated.

Transportation

Only three percent of Americans who are not vaccinated say a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine is that they do not have a reliable way to get to a vaccination site, and an additional 7% say that is one of the reasons but not a critical one. Most unvaccinated Americans (89%) say this is not a reason. Vaccine refusers (2%) are equally likely as the vaccine hesitant (4%) to report this as a critical reason preventing them from getting a COVID-19 vaccine.

Barriers Are Highest for Black, Hispanic, and Young Americans

Among the groups with particularly high combined rates of vaccine hesitancy and refusal, Hispanic Protestants, Americans ages 18–29 and 30–49, Black Protestants, and all Black Americans are significantly more likely than all hesitant and refuser Americans to say logistical factors impede their ability to get vaccinated.

More than four in ten Hispanic Protestants (44%) say time to get vaccinated or deal with the possible side effects is a critical reason (22%) or one of the reasons (22%) they have not gotten vaccinated yet. More than one-third of Americans ages 18–29 (38%) and 30–49 (37%), Black Protestants (37%), and Black Americans (36%) say the same. Black Protestants are most likely to report that a health condition is a critical reason (18%) or one of the reasons (18%) they have not gotten vaccinated. Substantial portions of Hispanic Protestants (34%) also report that health is a critical reason or one of the reasons they are not vaccinated. Hispanic Protestants are most likely to report that lack of childcare is an issue (21%), but one in five Black Americans (20%) struggle with this as well. The same is true of having reliable transportation—Hispanic Protestants (21%) and Black Protestants (18%) are most likely to say that is a critical barrier or one of the reasons they are not yet vaccinated.

Across all four barriers, Republicans, rural Americans, and white evangelical Protestants are no more likely than all Americans to report these as critical challenges or reasons they have not gotten vaccinated, despite their lower-than-average vaccination rates.

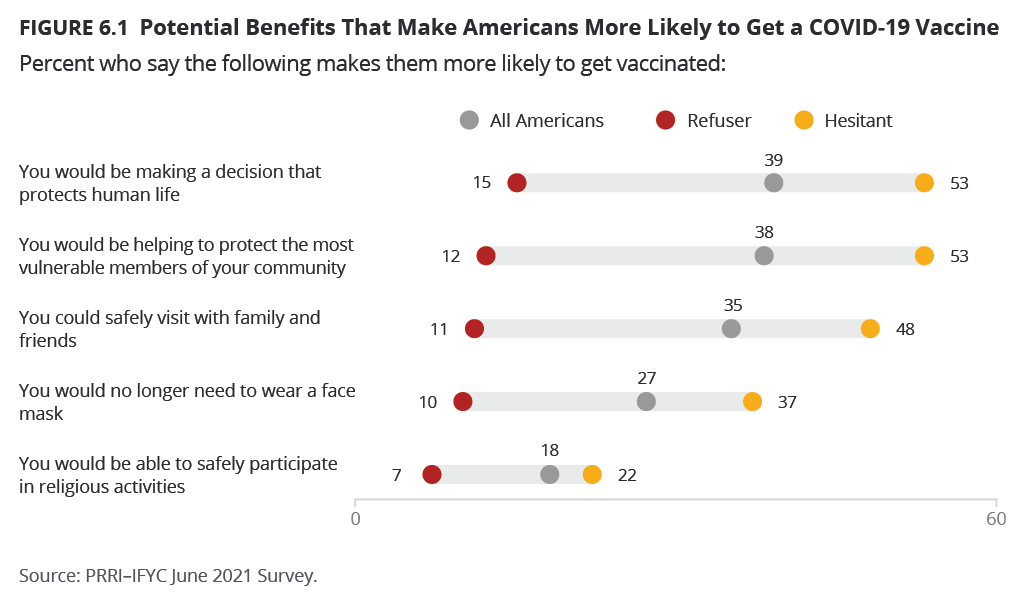

Potential Benefits of Vaccination

Protect Human Life

Nearly four in ten Americans (39%) say that the idea that they would be protecting human life makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19. This percentage jumps to 53% among the vaccine hesitant but drops to 15% among refusers. Most refusers (68%) say it makes no difference, compared to nearly half of Americans (47%) and 39% of the vaccine hesitant.

Protect the Most Vulnerable in the Community

About four in ten Americans (38%) say that protecting the most vulnerable members of their community makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19. This percentage jumps to 53% among the vaccine hesitant but drops to 12% among refusers. About seven in ten refusers (71%), half of Americans (50%), and 41% of the vaccine hesitant say it makes no difference.

Safely Visit Family and Friends

More than one-third of Americans (35%) say that the ability to safely visit family and friends makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19. This percentage jumps to 48% among the vaccine hesitant but drops to 11% among refusers. About three in four refusers (73%), a slim majority of Americans (53%), and about half of the vaccine hesitant (47%) say it makes no difference.

No Longer Need to Wear a Mask

About one in four Americans (27%) say that no longer needing to wear a face mask makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19. This percentage jumps to 37% among the vaccine hesitant but drops to 10% among refusers. Majorities of refusers (73%), all Americans (59%), and the vaccine hesitant (56%) say it makes no difference.

Safely Participate in Religious Activities

Less than one in five Americans (18%) say that the ability to safely participate in religious activities makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19. This is about the same among the vaccine hesitant (22%) but notably drops to 7% among refusers. Majorities of refusers (73%), the vaccine hesitant (65%), and all Americans (64%) say it makes no difference. Not surprisingly, Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year are much more likely than those who attend seldom or never to say that the ability to safely participate in religious activities makes them more likely to get vaccinated against COVID-19 (23% vs. 15%). This gap is higher among the vaccine hesitant (28% vs 18%) but does not differ significantly among refusers (10% vs. 6%).

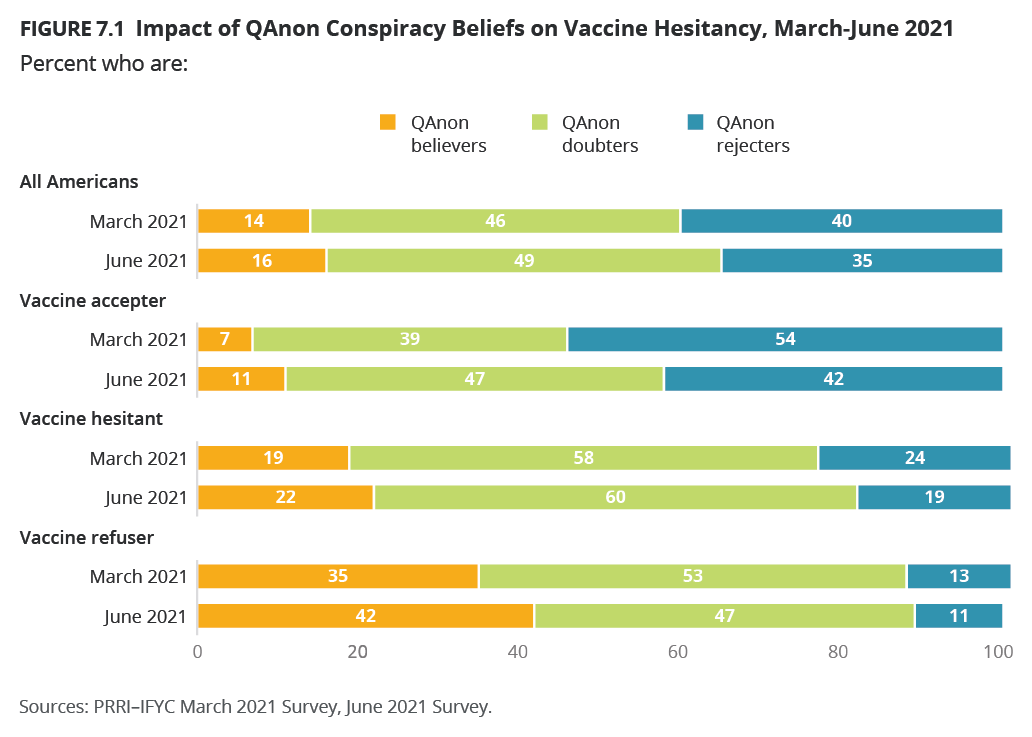

QAnon Conspiracy Beliefs and Vaccine Hesitancy

PRRI created a composite measure from three statements involving the core tenets of QAnon beliefs: “The government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation”; “There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders”; and “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

Responses to these questions were recoded into three groups: (1) QAnon believers, or respondents who completely or mostly agreed with these statements (16%); (2) QAnon doubters, or respondents who mostly disagreed with these statements (49%); and (3) QAnon rejecters, or respondents who completely disagreed with all three statements (35%). The percentage of both QAnon believers and doubters was about the same between March and June, while there are slightly fewer QAnon rejecters in June than there were in March (14%, 46%, and 40%, respectively).

Republicans (23%) are significantly more likely than independents (14%) and Democrats (10%) to be QAnon believers. A majority of Republicans (58%), nearly half of independents (49%), and over four in ten Democrats (42%) are QAnon doubters. Nearly half of Democrats (48%) are QAnon rejecters, compared to 37% of independents and 19% of Republicans. These attitudes have remained virtually the same since March among Republicans and independents but shifted among Democrats. Between March and June, Democrats have become more likely to be QAnon doubters (35% in March vs. 42% in June) and less likely to be QAnon rejecters (58% in March vs. 48% in June).

Among vaccine refusers, the proportion who are QAnon believers went up seven percentage points, from 35% in March to 42% in June, while the proportion who are QAnon doubters (53% in March vs. 47% in June) and rejecters (13% in March vs. 11% today) dropped slightly. Among the vaccine hesitant, 22% are QAnon believers, 60% are QAnon doubters, and 19% are QAnon rejecters, with the latter dropping five points from 24% in March. The views of vaccine accepters have shifted most since March 2021: The proportion who are QAnon believers went up, from 7% in March to 11% in June; and the proportion of QAnon doubters also rose, from 39% in March to 47% in June; while the proportion of QAnon rejecters went down, from 54% in March to 42% in June.

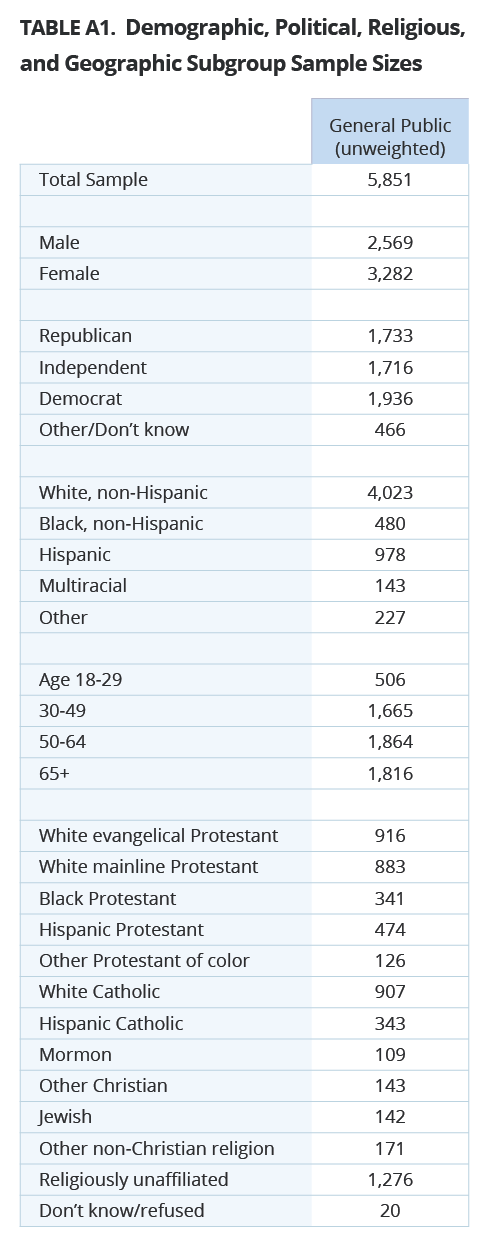

Survey Methodology

The survey was designed and conducted by PRRI and IFYC among a random sample of 5,123 adults (age 18 and up) living in all 50 states in the United States and who are part of Ipsos’s Knowledge Panel and an additional 382 who were recruited by Ipsos using opt-in survey panels to increase the sample sizes in smaller states. An additional 346 Hispanic Protestants were recruited to increase sample sizes among this group. Interviews were conducted online between June 7 and 23, 2021. The survey was made possible by generous support from the Open Society Foundations.

Respondents are recruited to the KnowledgePanel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS – a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

Respondents are recruited to the KnowledgePanel using an addressed-based sampling methodology from the Delivery Sequence File of the USPS – a database with full coverage of all delivery addresses in the U.S. As such, it covers all households regardless of their phone status, providing a representative online sample. Unlike opt-in panels, households are not permitted to “self-select” into the panel; and are generally limited to how many surveys they can take within a given time period.

The initial sample drawn from the KnowledgePanel was adjusted using pre-stratification weights so that it approximates the adult U.S. population defined by the latest March supplement of the Current Population Survey. Next, a probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling scheme was used to select a representative sample.

To reduce the effects of any non-response bias, a post-stratification adjustment was applied based on demographic distributions from the most recent American Community Survey (ACS). The post-stratification weight rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, Census division, metro area, education, and income. The sample weighting was accomplished using an iterative proportional fitting (IFP) process that simultaneously balances the distributions of all variables. Weights were trimmed to prevent individual interviews from having too much influence on the final results. In addition to an overall national weight, separate weights were computed for each state to ensure that the demographic characteristics of the sample closely approximate the demographic characteristics of the target populations. The state-level post-stratification weights rebalanced the sample based on the following benchmarks: age, race and ethnicity, gender, education, and income.

These weights from the KnowledgePanel cases were then used as the benchmarks for the additional opt-in sample in a process called “calibration.” This calibration process is used to correct for inherent biases associated with nonprobability opt-in panels. The calibration methodology aims to realign respondents from nonprobability samples with respect to a multidimensional set of measures to improve their representation.

The margin of error for the national survey is +/- 1.65 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence, including the design effect for the survey of 1.7. In addition to sampling error, surveys may also be subject to error or bias due to question wording, context, and order effects. Additional details about the KnowledgePanel can be found on the Ipsos website: https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/solution/knowledgepanel

Endnotes

[1]“Other Christian” includes all Christians who are not specified in any other category, including Catholics who are Black, Asian American or Pacific Islander, multiracial, Native American, and any other race or ethnicity; Jehovah’s Witnesses; Orthodox Christians; and any other Christian group. “Other non-Christian religion” includes those who are Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Unitarian Universalist, or any other world religion.

[2] “Other Protestant of color” includes all Protestants who are not white, Black, or Hispanic (including Asian American or Pacific Islander, multiracial, Native American, or any other race or ethnicity). Categories were combined due to sample size limitations.

[3]QAnon beliefs are measured based on respondents’ feelings about three statements: (1) The government, media, and financial worlds in the U.S. are controlled by a group of Satan-worshipping pedophiles who run a global child sex-trafficking operation; (2) There is a storm coming soon that will sweep away the elites in power and restore the rightful leaders; and (3) Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country. Believers mostly agree with these statements, whereas doubters are generally negative toward them and rejecters strongly disagree with all three statements.

[4]“Americans of other races” includes Asian American or Pacific Islander, Native American, and any other single race or ethnicity. Categories were combined due to small sample sizes. The number of cases of Americans who identify with other racial groups without a college education is 69, the number of cases of multiracial Americans is 77, the number of cases of Americans without a college education is 77, and the number of cases of those with at least a four-year degree is 66. Despite the small sample sizes, differences in education are statistically significant.

[5]Sample size is insufficient to report Hispanic Protestants who are hesitant by attendance.

[6]White Catholic and white mainline Protestant sample size is insufficient to report by attendance. White Catholic hesitant n=93. Black Protestant and Hispanic Catholic were included in this analysis in March, but the sample sizes are too small to report due to the decrease in sample sizes in the hesitancy category between March and June.

[7]The sample size for Hispanic Catholics who are vaccinated and attend services is n=88.

[8]The number of cases for other religious groups is <100 for this question.

[9]The number of cases for multiracial Americans is 73.

[10]Sample sizes for the remaining religious groups are too small to report.

[11]Even though there are only 69 cases of Democrats who are refusers, the differences between them and Republicans is statistically significant.

[12]The number of cases who are vaccine refusers and live in the Northeast is 84. However, the differences between them and those who live in the Midwest are statistically significant, while the differences between those who live in the Midwest and those who live in the West are significant at the .10 level.

[13]Even though the number of cases for young vaccine refusers is 65, the differences between them and Americans ages 30–49 are statistically significant.

Recommended Citation

“Religious Identities and the Race Against the Virus: Successes and Opportunities for Engaging Faith Communities on COVID-19 Vaccination” PRRI (July 28, 2021). https://www.prri.org/research/religious-vaccines-covid-vaccination