Amid all the ongoing changes in the country that generally favor Democrats, is it still possible that President Donald Trump will be reelected in 2020? Because I study religious and demographic change, I hear this question a lot. Much of the early punditry on Trump’s reelection prospects has focused on complex Electoral College scenarios—insights that, while valuable, shed little light on the bigger picture. I’ve come to answer the question this way: Yes, it is possible Trump gets reelected. While Democrats have the long-term demographic winds at their back, Republicans have a time machine: a consistent skew in ethnic and religious voter-turnout patterns that, in national elections, has the effect of turning back the demographic clock eight or more years

I first stumbled over this Republican secret weapon while analyzing the political implications of the changing U.S. religious landscape. In the decades since Ronald Reagan’s pivotal election in 1980, describing the political behavior of religious groups has been a simple task. Majorities of white Christian groups—including white evangelical Protestants, white mainline Protestants, and white Catholics—have voted for Republican presidential candidates, while majorities of every other group—including nonwhite Protestant and Catholic Christians, non-Christian religious Americans, and the religiously unaffiliated—have voted for Democratic presidential candidates. The upshot: Any significant change in white Christians’ share of the electorate has major partisan implications.

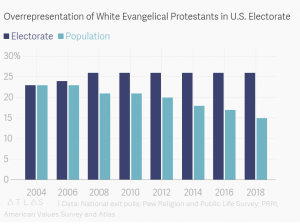

As I described in my 2016 book, The End of White Christian America, something remarkable has happened in the past decade: For the first time in our history, the United States ceased to be a majority white Christian country; white Christians were 54 percent of the population in 2008 but only 47 percent in 2014. Since the book’s publication, those trends have continued unabated. According to data from the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI), where I am CEO, only 43 percent of the country identified as white and Christian by the 2016 election, and this number drops again to 41 percent in the most recent 2018 data. Notably, the white evangelical Protestant subgroup, the group that threw 80 percent of its votes behind Trump in 2016, has experienced a similar decline. White evangelical Protestants dropped from 21 percent of the population in 2008 down to 17 percent in 2016 and further to 15 percent by 2018, according to PRRI studies.

These trends seem to fly in the face of the electoral results in 2016. While white Christians composed only 43 percent of the population in 2016, they constituted an estimated 55 percent of voters. And although white evangelical Protestants composed only 17 percent of the public in 2016, they were 26 percent of voters. In other words, in the electorate, white Christians overall were 12 percentage points overrepresented, and white evangelical Protestants were nine percentage points overrepresented.

When white Christians stepped into the voting booth in 2016, their electoral power was comparable to their share of the population back in 2008. The Republican time machine took white evangelicals on an even longer journey. They jumped back to the middle of the George W. Bush era, the last time they made up nearly a quarter of the population.

What fuels the Republicans’ political strength, in other words, is not current white Christian population levels, but the fact that white Christians historically turn out to vote at higher rates than nonwhite and non-Christian Americans. These higher turnout rates are driven by a number of factors. Voting is highly correlated with other forms of civic participation, such as church attendance. Voting is also highly correlated to education levels, and white Christians are more likely than nonwhite Christians to hold a four-year-college degree. Finally, voting is a habit that has been strongly emphasized in white Christian churches, especially among white evangelicals since the rise of the Christian right in the 1980s.

What does all of this mean for 2020? While Republicans will still benefit from the population dynamics of yesteryear, the maximum lag is about two to three presidential-election cycles. According to current projections, 2024 will be the year that white Christians—already less than half the population—will be a minority in the electorate as well. Between now and then, on the one hand, Republicans will need to expand the base of their party if they want to continue to be competitive nationally.

Democrats, on the other hand, need to take seriously the continued strength of this underappreciated Republican asset. Demographic trends may be a bright light on the Democratic Party’s horizon. But unless turnout patterns shift dramatically, next year’s electorate will look more like the America of 2012, not 2020.

Originally appeared in The Atlantic on June 25, 2019